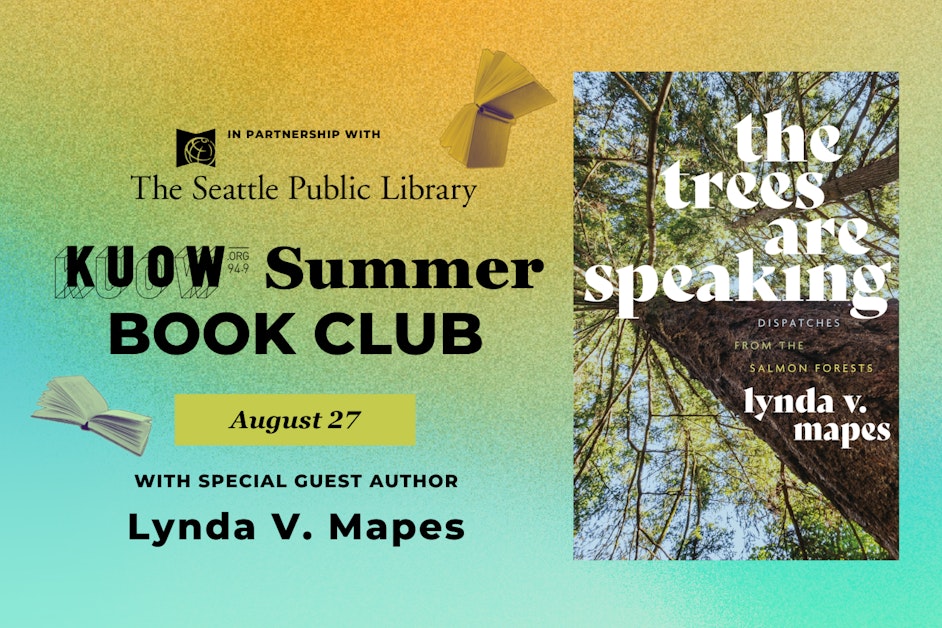

The KUOW Book Club is continuing its summer reading series with Seattle Public Library this month. We’re reading environmental journalist and author Lynda V. Mapes’ new book, “The Trees are Speaking: Dispatches from the Salmon Forests.” There’s a lot of ground to cover, so let’s dive in.

A

text like “The Trees are Speaking” runs the risk of being too academic, too dense for the average reader who wants to learn more but whose life is not devoted to the subject matter. But like Mapes’ other works and books that share shelf space with hers, the people who have dedicated themselves to the trees bring magic to the academia of it all.

Mapes is among them, matching her sources’ enthusiasm and awe for the outdoors. Their passion for the old-growth trees this book is about shines through and makes science feel almost like science fiction. A passage like this, describing so much life, would not seem out of place in a novel set on a lush alien planet:

Old trees matter. It is here that wildlife finds refuge, in the nooks, crannies, and caved-in nest cavities and cool ferny glades of their understory. The thick, complex, and furrowed bark of older trees also creates the homes for insects that in turn feed birds, bats, flying squirrels, and other species. This assemblage of ages and species can be created only over centuries. Age and diversity also make these forests resilient to fire, insects, and drought. In dry summers of the Pacific Northwest, old trees are capable of pulling huge amounts of water from deep in the soil, shared between their roots.

THE TREES ARE SPEAKING, PAGE 26

Except this isn’t a lush alien planet — it’s our planet. And Mapes is clear: We’re not doing our best to preserve it.

RELATED: Subscribe to the KUOW Book Club newsletter here

You don’t have to take her word for it. “The Trees are Speaking” is supported by a host of researchers and environmental activists who have made incredible discoveries about the role of old-growth trees, alive and dead. Among them is Jerry Franklin, a world-renowned forest ecologist who has been called the Father of New Forestry.

“I refer to [tree] plantations as one of forestry’s great deceptions,” Franklin said. “We were fooled. People have to realize that all is not well. Foresters deceived themselves into thinking plantations are forests, and they are not. These are great for stockholders, but nobody else.”

THE TREES ARE SPEAKING, PAGES 37-38

Even that’s arguable — that stockholders benefit — in the long run, as Mapes and several Indigenous sources explain.

This book is not just a devotional to forests and the intricate webs of life that dwell therein, but also a catalog of the ways people have failed them. Well, to be more specific, the ways non-Native people have failed them.

RELATED: Summer book club concludes with reflection on irreplaceable old-growth forests

Mapes traveled the logging roads that have changed the landscape of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. She witnessed the barren clear-cuts left by logging companies, which spray herbicides to prevent a dynamic understory from growing there amid more profitable, farmed trees. And she detailed the ways colonizers tour through this landscape without regard for those who were there long before them.

Perhaps more importantly, Mapes laid out the ways Native peoples have been stewards of this land for generations, long before Europeans lay claim to it. In this way, she and her sources show readers that preserving the land and benefiting from it are not mutually exclusive if done right.

Nuchatlaht First Nation elder and councillor Archie Little, who has fought to restore ancestral territory on Vancouver Island, put it this way:

“Look at the First Nations, we survived for thousands and thousands of years, in healthy, prosperous governments and cultures,” he said. “The non-Indians hitting our shores saw the wealth of the land and the ocean and the people. But it was community wealth. They saw personal gain, to take and take for profit. Not manage it wisely for the future.”

THE TREES ARE SPEAKING, PAGE 99

The thing about “The Trees are Speaking,” and any book about a dwindling natural wonder, is that readers are bond to feel distraught as often as they are delighted.

For every lush description of an ancient tree or the way a dead log has given way to so much new life or simply the sight of a wolf’s paw-print in the mud, there is a devastating tally of harm still being done. In some cases, Mapes was there mere minutes after ancient trees were cut down alongside the people trying to save them. Their devastation is made palpable.

Author and scientist Suzanna Simard, a member of a research effort called the Mother Tree Project and professor at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, reflected on a recently “maimed landscape” as a truck hauled away massive logs:

“It’s a tree hearse,” Simard said of the logging truck, as we walked back to her truck. … “I know we can’t save every tree. But we have to do a better job. We are going to need wood, but it should not be the old-growth. That was all cedar. It just makes me feel sick. And the fact we have seen it, day after day after day, all over the country, I’m sure those trees are a thousand years old. People grow so numb to it, we all are.”

THE TREES ARE SPEAKING, PAGE 56

Mapes isn’t the first author who has tried to communicate this message to the reading masses. KUOW Book Club readers may recall similar warnings in our October 2024 pick, the Timothy Egan classic “The Good Rain.”

RELATED: ‘Being is bliss’ in Timothy Egan’s ‘The Good Rain’ — and still is three decades later

That is to say, “The Trees are Speaking” is not likely to turn the tide and save our forests on its own. But perhaps it can help us to become less numb. And that has to count for something.

—————————————————————————————-

Spoiler alert: For those of you who like to plan ahead, we’ll be reading Seattle author Daniel Tam-Claiborne’s debut novel, “Transplants,” in September. And Daniel is set to join me for an interview to conclude our reading.

“Transplants” follows two young women — one Chinese and one Chinese American — on a university campus in rural Qixian, where they’re both met with hostility. Together, they learn what it means to be their truest selves in a world that doesn’t know where either of them belongs. It’s an exploration of race, love, power, and freedom.

Look out for the reading schedule on Sept. 1.