The San Diego Padres need more power in their lineup to put them over the top. The team is 25th in the league in slugging, and would be in a worse spot if it didn’t make so much contact. The Padres could use some more oomph from Fernando Tatis Jr., in particular. Though the 26-year-old outfielder is having a fine season based on patience, contact, base running and defense, the power isn’t there. In fact, he’s having the worst slugging season of his career.

So where’s that power for Tatis? Why is it down from the level he established early in his career and even the past couple of years? After Tuesday night’s game, Tatis has now gone a career-worst 106 consecutive plate appearances without a homer. His previous high was 94, which was set earlier this season.

“I’m just trying to be a good hitter, get on base, and yeah, I’m not hitting homers,” he said this past weekend regarding his lack of over-the-fence power.

“He’s hit the ball hard. It’s a lot of things that you want to see,” Padres hitting coach Victor Rodriguez said recently. “Controlling his effort level, swinging at good pitches and being able to hit the ball to all fields.”

It’s true that Tatis is swinging the bat fast and hitting the ball hard, as his hard-hit rate is 15th-best among qualified hitters. But that hard contact is not coming in the air. And that may have something to do with where he’s making contact with the ball.

Throughout a swing, the bat has different angles with respect to the ball approaching the plate. As the bat comes down from the shoulders, through the hitting zone and then back up, it creates different “attack angles.” Here’s an animation, courtesy of Baseball Savant, showing Alex Bregman hitting a home run — look at the angles of the bat throughout the swing.

As you can see, if Bregman had made the contact later in the path of the ball (deeper), his bat would not have had the same loft. If he’d made the contact earlier in the path of the ball (out in front more), it may have had too much loft. This concept is why getting the ball out in front of the plate has been associated with power — the bat is more likely to have a good attack angle on the ball that will lead to power.

This contact point is now tracked on Baseball Savant as the “intercept point,” and Mike Petriello showed on MLB.com that the best overall production and the best power production is at 36 inches out in front of the batter’s center of mass. The best intercept point for contact is 30 inches.

Since baseball started tracking the intercept point, Tatis has not had a lower intercept point in any month than the 27.6 inches he’s showing this August. In other words, he’s letting the ball travel deeper into his bat path more than ever. That has been great for putting the ball in play, and so his contact and strikeout rates are the best of his career, but it’s also pushed his power production down to the lowest point of his career.

It’s clear from the numbers and the eye test that he’s been tinkering with his stance and his approach all year.

“I’m still searching and just trying to compete every single day,” Tatis said.

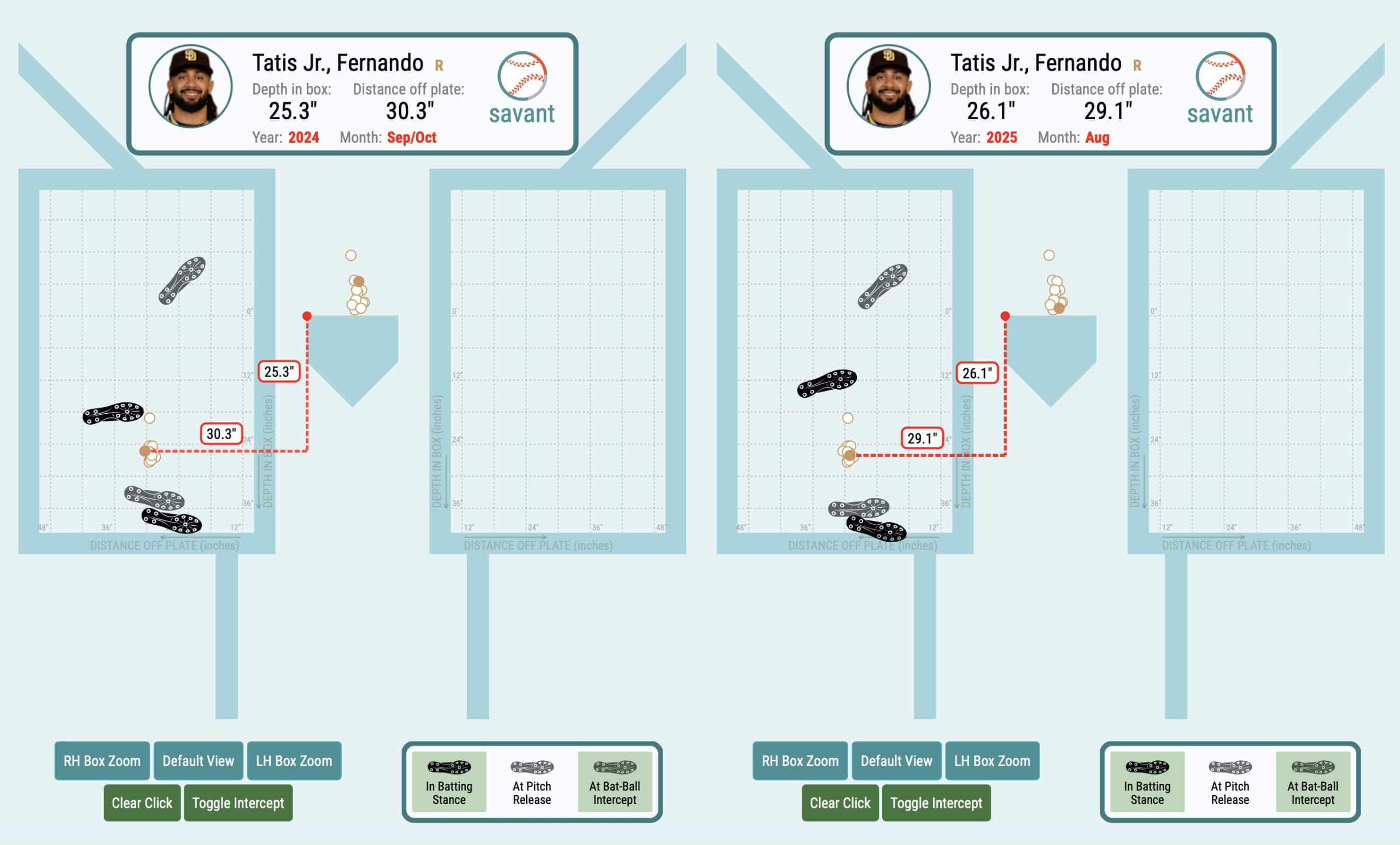

The difference between his stance and intercept point late last year (left) and this past month (right) shows just how much more open his stance is now, and how much further he’s letting the ball travel in the zone.

He’s standing more spread out this year, with a more open stance, closer to the plate and further back in the box. Even recently, he’s made more changes, as he’s gone from an average of 41 degrees open before this past weekend to 10 degrees open, more like he was last season. He’s still letting the ball travel four inches further before making contact, which may just be robbing him of power.

“Anything that you hit the other way and you get results (on) is always a good sign,” said Rodriguez, who has a different take on the subject. “You let it travel, and you just went with it, instead of trying to do too much with it.”

Looking at comparable players, Tatis has top-quartile bat speed and a 30-degree swing tilt — a swing that’s on the flatter end but not as flat as the swings for Randy Arozarena or Corbin Carroll. We can look for comps based on those two aspects alone, and we’ll find a list of 25 players that run the gamut from Seiya Suzuki and Bobby Witt Jr. to Nathaniel Lowe to Christian Walker.

Now, let’s separate that group by who lets the ball travel (lower intercept point) and who goes and gets the ball out front (higher intercept point). The entire group averages a 30-degree tilt and a 73 mph swing speed like Tatis, but the difference in results between the “let it travel” and “go get it” groups is fairly stark, given how much else they have in common.

Tatis’ swing comps, separated

GroupInterceptSluggingIdeal Attack Angle

Let it travel

29

0.424

50.90%

Go get it

33

0.449

55.20%

To recap, all of these players swing equally fast and have similarly shaped swings, but the hitters who go get the ball out in front get 25 points more slugging by hitting the ball at the right angles more often. As a group, the “go-getters” pull the ball more, hit the ball in the air more, barrel the ball more and have better overall production.

It’s one thing to say that Tatis needs to get the ball out in front more, and another to do that successfully, as his hitting coach points out. Tatis is pulling the ball in the air less than ever, but could the problem be that he wants to pull the ball in the air more often?

“I think a lot of times it’s because you want to,” Rodriguez said of the desire to lift and separate. “You want to. And when you want to, what do you do? You open up and you cheat. But when you don’t want to and you’re in a good direction, you let the ball and your hands do the work. When you’re trying to pull, that’s when you get into trouble. But when you’re in a good position … and the ball is inside, you react the right way — you lift it. So it’s a matter of staying with a good approach to the big part of the field and letting his ability — his quickness — take over.”

Letting the ball travel has been good for Tatis’ strikeout rate so far this year, but has dampened his power production. Even getting the ball out in front another three inches, as he did last season, could get him back the power he’s been missing this year. Perhaps it’s wise to embrace a few more swings and misses if that aggression out front brings back the homers.

But the trick might be, somehow, to go get that ball without opening up, attacking within ideal mechanics. Controlled aggression. So simple when you say it that way.

(Photo: Carmen Mandato / Getty Images)