The following article considers critical limitations upon the development of strategies to take forward what many regard as much-needed reform to health and care services in Scotland. A second article will look at what might be done to address these constraints.

In its report on the NHS in Scotland in 2023, Audit Scotland (AS) noted that there was “a range of strategies, plans and policies in place for the future delivery of healthcare, but no overall vision. To shift from recovery to reform, the Scottish Government needs to lead on the development of a clear national strategy for health and social care.” It was added that the “current absence of an overall vision makes longer-term planning more difficult for NHS boards.”

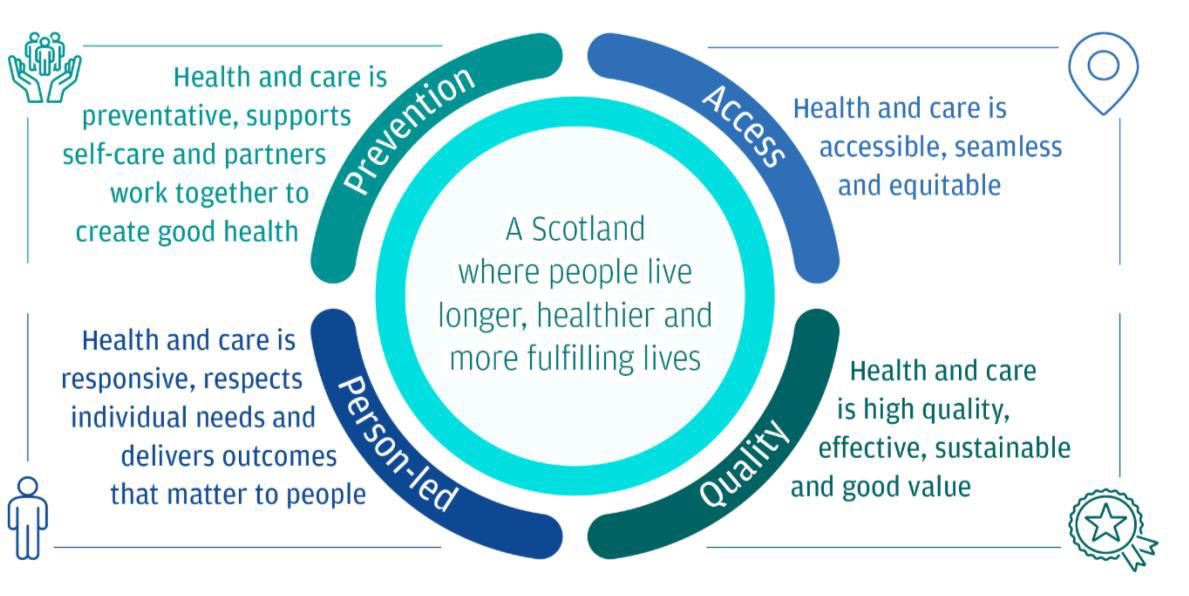

The following year AS, in its report NHS in Scotland 2024, repeated its call for a national strategy for health and social care, but noted that that the Cabinet Secretary for NHS Recovery, Health and Social Care, Neil Gray, had by then described his overarching vision for health and care. This vision was of “a Scotland where people live longer, healthy and fulfilling lives”, supported by four key areas of work – improving population health, a focus on prevention and early intervention, providing quality services, and maximising access. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1: Health And Care Vision

The Cabinet Secretary was, according to AS, said to have been clear that no work would be undertaken to produce a strategy setting out how the Scottish Government intends to deliver this vision. Instead, it was argued that existing plans and strategies were already aligned to his vision. Mr Gray told the Scottish Parliament on June 4 2024 that “I am not looking to publish another strategy. Our work is already being guided by multiple plans, notably the National Clinical Strategy of 2016. Our task now centres on listening and delivery.”

AS however argued that Gray’s particular vision “is a restatement of the 2020 vision and is reliant on a number of the same delivery plans.” AS viewed the 2020 vision not to have achieved its ambitions and was lacking “in significant operational detail in terms of how it will contribute to ensuring that services remain affordable.” If this 2020 vision did not meet expectations of a strategy for AS, one has to recognise that the multiple use of the terms “strategies”, “visions”, “plans” and subsequently “frameworks” probably muddied the water as to what was actually under consideration.

That said, the Government did thereafter attempt to promote a renewed specification of its change agenda by producing in 2025 three plans for health and care. The first was an Operational Improvement Plan (March) which had been a direct recommendation from AS contained in The NHS in 2024. The second was a population health Framework covering the period 2025-2035 and the third a service renewal Framework for health and social care also covering the period 2025-2035. Interestingly, neither of these latter two was described as a strategy. Both plans were published in June 2025 and were jointly sponsored by Cosla. All three plans were to build upon the NHS Recovery Plan 2021-2026 and together were intended to realise the Health and Social Care Vision set out by the Cabinet Secretary in Parliament in June 2024, now in a more formalised version. Whatever the issues of nomenclature, clearly there had been a rethink on the need for strategic plans.

The foreword to the Operational Plan hinted at a reform agenda connected to the Government’s wider ambitions for the NHS, but the Cabinet Secretary emphasised that this particular document “is focused on the short term.” In reality what it does, drawing upon plans developed by NHS Boards, is bring forward pre-existing initiatives rather than adopting truly innovative changes. These initiatives are to be directed at improving access to treatment, shifting the balance of care, improving access to health and social care services through digital and technological innovation, and developing various prevention services. The Operational Plan is not really a reform document of any hue. Moreover, the total additional funds underpinning it represented about 2.4% of the total Health and Social Care budget for 2025-26, indicating the marginal nature of the potential changes. Instead, it has the hallmarks of a reactive response to pressing problems that over the years can be said to have displaced fundamental reform and underwritten continuing patterns of service provision.

The population health paper (Scotland’s Population Health Framework 2025-2035) is committed to an unspecified improvement in Scottish life expectancy by 2035 whilst also reducing the life expectancy gap between the most deprived 20% of local areas and the national average. The Framework was supported by an evidence review (Scottish Government Population Health Framework: Evidence paper). The background to the Framework was that since the mid-2010s the long-term trend in increasing life expectancy had effectively stalled and then moved into reverse, mental health had deteriorated over the same period and health inequalities had grown. These setbacks were attributed to economic austerity and the existence of inequalities of income, wealth and power along with other adverse social circumstances such as poor housing and insecure work and “health harms” such as obesity and alcohol consumption. Improving the health of Scots and closing the health gap between “rich” and “poor” is said to require “macro-level policies” with an emphasis on primary prevention.

The case was being made – and not for the first time – that better health for all lay through significant socio-economic reform, although improvement in access to, and use of, health and care services was also said to be needed to address health inequalities. The supporting evidence paper did acknowledge that the current evidence base that could be translated into effective policy solutions is far from fully developed. Nonetheless, it was concluded that the evidence paper “outlined a range of measures and frameworks… which can form the basis of an effective prevention focused system.”

The Population Health Framework does not amount to a concrete programme of policy actions. The Initial Actions set out in the Population Health Framework are very general and are preparatory in nature rather than directly pursuing new, innovative policy interventions. For example, one Initial Action is to “Develop a Healthcare Inequalities Action Plan”. Another proposes that a “Health and Work Action Plan” is published. A third calls for an action to “Develop new approaches to resource allocation that support prevention across health and other public services.”

Of course, improving the health of the population is by any standards a major public policy challenge, not helped by the state of the public finances. There is a multiplicity of social causes to poor health, the understanding of which is sometimes ambiguous because of the sheer complexity of the factors involved. Similarly, responsibility for the causes of, and answers to, ameliorating poor health lie with a myriad of organisations that makes matters of strategic influence and coordination by government exceedingly difficult. However, the sheer scale of preliminary work that still needs undertaken should raise concerns. There is a lot of catching up to do. It would seem – if improving the health of the population and reducing health differences are priorities – that in past years there has not been enough strategic development work in support of these ambitions.

The final one of the three plans is the Health & Social Care Service Renewal Framework 2025-2035. As the Cabinet Secretary told Parliament at its launch, it “sets out a clear path ensuring a sustainable, high-performing health and social care system that meets the future demands and evolving needs of our population” while also “ensuring long-term financial sustainability.” At its core, however, the document is in effect another timetable for producing plans to bring about significant change over a ten-year period. There are few defined changes to health and care services contained within it, which gives an impression that the strategy for reform still requires significant development. The Framework is built around a list of Renewal Principles:

Prevention Principle: Prevention across the continuum of carePeople Principle: Care designed around people rather than the “system” or “services”Community Principle: More care in the community rather than a hospital focused modelPopulation Principle: Population planning, rather than along boundariesDigital Principle: Reflecting societal expectations and system needs [concerning both people’s experience of care and making services modern, joined up and efficient].

These Principles are summarised in the document in terms of what they generally imply for services going forward, which is elaborated by some illustrative – admittedly selective – examples of current services that demonstrate possibilities and by some lists of high-level service changes that will help to create the right conditions to align services with the Principles. The Framework also contains so-called enabling shifts in resources and finance and on how performance and outcome measures can be developed to assess whether progress against the desired changes is being made.

What is not there is a complete suite of service changes needed to reform health and social care. Indeed, this Renewal Framework explicitly highlights that the required range of changes to services will only become clear in years three and four of the 10-year timescale, and that the renewed health and social care system will not have all the components in place until subsequent years, although proven innovations will continue to be fast-tracked. There are some examples of interventions that have led or could lead to improvements. But overall the plan is a familiar repetition of the benefits of particular types of changes (e.g. prevention and early intervention, new models of hospital care and clinical benefits of high throughput) that does not elaborate upon how general principles can be converted into new, innovative interventions to realise the anticipated benefits. Instead, most of the document is taken up with stating what the ambitions are, not how they can be realised.

In 2019, AS called for the development of “a new national health and social care strategy to run from 2020 that supports large-scale, system-wide reform, with clear priorities that identify the improvement activities most likely to achieve the reform needed.”

The Covid pandemic of course significantly got in the way of making progress with a health and care strategy, but the subsequent delay looks to be odd given that AS along with many other observers have been calling out for systematic reform of health and social care, particularly around financial sustainability. The Government looks slow off the mark, and does not have a cupboard full of fresh, effective interventions upon which to draw. This again suggests that strategic development for health has over many years not been given the attention needed.

These three plans raise questions about how well placed the Scottish Government is to set out the strategic changes that will bring about the reform to the health and care system that First Minister John Swinney outlined in a speech on January 27 2025, signalling a new effort to have a systematic approach to improving health care. As noted, the Operational Delivery Plan is not a strategic document but about short-term, marginal improvements. In this sense it runs counter to strategic change by using quick fixes that are ready and available – rather than contributing steps that are explicitly linked to longer-term strategic change. This seems a missed opportunity to kick-start fundamental reform.

The Population Health Framework and the Health and Social Care Renewal Plan were, however, a very different form of document, each with a decade-long timescale. However, neither were in fact strategies but what might be termed “pre-strategies” that contain a timetable for producing the different components that would form in due course a strategy. A proper strategy would require setting out actual interventions to deliver major reform of how the health and care system actually operates in practice and which as a result delivers significant improvement in the population’s health and the health and care provision people receive. These plans will need to set out in some level of detail how resources will be acquired, organised and mobilised towards achieving particular outcomes. This must go well beyond current policy rhetoric. The outcomes will have to incorporate measurable improvement to people’s health and well-being in a variety of ways so that progress against strategic aims can be assessed and confirmed.

Certainly both documents are explicit that this will take time and that the full 10 years – and possibly more – will be needed for development and delivery. There is, however, a critical question that goes beyond the patience implied by this timeframe. Does the Scottish Government have the necessary strategic capability such that the health system in Scotland can be set on the path to real reform? Looking back, it is possible to reference ten or more plans since 1976 from the Scottish Office/Executive/Government that have included most of the strategic themes and ambitions contained in these two current Framework documents, especially regarding health and social care. Yet over those five decades these plans have never been seen to have resolved the strategic health challenges facing the country. Instead, each one is a revisiting of a familiar agenda. Each time, previous Scottish administrations simply appear to have gone around a familiar circuit without seriously considering and describing why things will be different this time to enable fundamental change to happen.

In a second piece I will explore in the Scottish context why developing health strategy is such a tale of woe and what might be done about it so that all the good ideas on health reform, including those from Enlighten’s NHS2048 forum, can be translated into strategic changes that make a difference for the people of Scotland.

Peter Williamson taught and researched health care policy and management at Aberdeen Medical School, was a strategy director for NHS Boards, and led policy work on health and innovation for the Scottish Government.

References

Scottish Government/NHSScotland Achieving Sustainable Quality In Scotland’s Healthcare: A ’20:20’ Vision (2011)

NHS Scotland A Route Map to the 2020 Vision for Health and Social Care (2013)

Scottish Government A National Clinical Strategy For Scotland (February 2016)

Audit Scotland NHS in Scotland 2019 (October 2019)

Scottish Government NHS Recovery Plan 2021-2026 (August 2021)

Audit Scotland NHS in Scotland 2023 (February 2024)

Scottish Government Vision for health and social care: Health Secretary speech – Health Secretary Neil Gray’s opening speech to Scottish Parliament on 4 June 2024 (https://www.gov.scot/publications/health-secretary-opening-speech-vision-health-social-care/) (Accessed 28/07/25)

Audit Scotland NHS in Scotland 2024: Finance and performance (December 2024)

Scottish Government An Operational Improvement Plan (March 2025)

Scottish Government Strengthening Scotland’s NHS: New plan to focus on delivery (Press Release) (31 March 2025). (https://www.gov.scot/news/strengthening-scotlands-nhs/) (Accessed 28/07/25)

Scottish Government-COSLA

Scotland’s Population Health Framework 2025-2035 and Population Health Framework: Evidence paper (June 2025).

Scottish Government-COSLA Health & Social Care Service Renewal Framework 2025-2035 (June 2025)

Scottish Parliament, Meeting of 17 June 2025, a statement by Neil Gray (Cabinet Secretary for Health and Social Care) on delivering reform and renewal for health and social care.