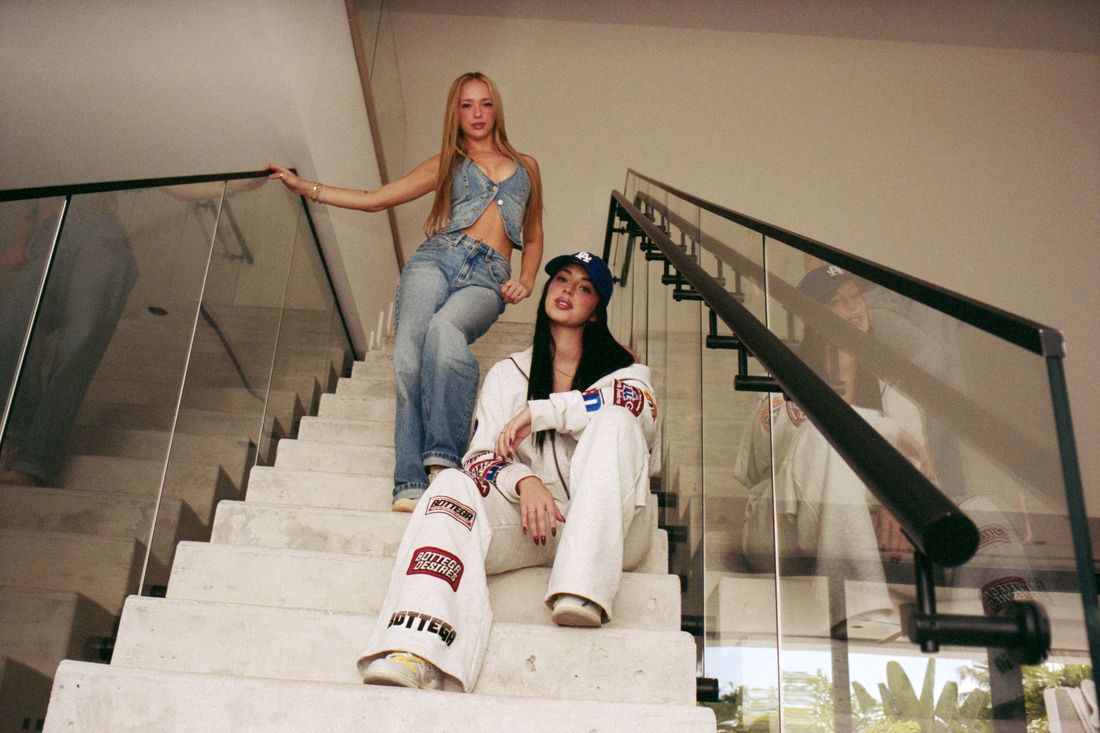

Julia Filippo, left, and Camilla Araújo at Araújo’s home in Miami, which Araújo and her boyfriend bought in April for $5.2 million.

Photo: Ashley Markle for New York Magazine

This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

On a hot July evening in Miami, Julia Filippo and Camilla Araújo are on their hands and knees on the floor of a Target, hands gripping the dirty linoleum in full view of the employees, who are visibly annoyed and very aware that they are not here to shop. “My arms can’t be in it,” says Araújo, who looks strikingly like a younger Katy Perry as she maintains a push-up position, while Filippo, blonde, tan, and tiny, holds a display ad over Araújo’s head and films. They’re trying to re-create a viral video in which Target product advertisements replace their bodies in an optical illusion, neither noticing nor caring that they’ve already been reprimanded once for moving signage and that everybody is staring at them.

Not everyone is looking for the same reason. Boomer men turn their necks and leer brazenly, but another contingent is harder to notice at first. Two high-school-age girls start to trail behind us, nudging each other and giggling in Spanish. It takes them at least ten minutes to work up the courage to ask for a photo, which Araújo and Filippo pose for happily while Araújo’s boyfriend-slash-manager, Owen Lynch, snaps pictures. By then, the floodgates have opened and a small mass of other girls materialize. One wearing jorts and a cross chain approaches them. “I love your necklace!” says Araújo, to which the girl responds, “I’m, like, so high right now.” Another group, an adult woman shepherding a handful of teens, tells Araújo and Filippo they have a girl with them from Guatemala who speaks little English but that she’d like a photo. By the time the woman bids them hasta luego, Filippo is already instructing Araújo to lie down on the floor again.

Filippo and Araújo, both 23, built their careers on OnlyFans, a platform best known for porn. But the girls who ask them for photos aren’t the ones paying $4 per month to subscribe to their pages. They know them because Araújo and Filippo are in the Bop House. Like its forebearers the Hype House and 1600 Vine, the Bop House is a collective of influencers who regularly collaborate and cross-promote one another’s accounts while appearing to live and work in the same place, creating a fantasy for followers eager to imagine their faves all being friends IRL, too. Unlike previous iterations, the Bop House is made up of OnlyFans creators, its name derived from a social-media slang term for “slut.” On December 8, 2024, the @BopHouse Instagram account posted its first video of its two founding members, Sophie Rain, a then-20-year-old self-identified Christian virgin, and her “cousin,” 22-year-old Aishah Sofey, prancing poolside in slim-fit athleisure holding a sign emblazoned with the Bop House logo. Over the next few days, they introduced eight additional members — Rain, Sofey, and six other OnlyFans influencers, a mix of friends and internet acquaintances: Summer Iris, Alina Rose, Joy Mei, and Ava Reyes, plus Araújo and Filippo. At the time, each was between the ages of 19 and 24, and most shared the lethal combination of a Coke-bottle body with a girl-next-door face, if the girl next door looked like she had recently graduated from eighth grade.

Several members even wear braces, which they claim are orthodontic necessities. In loosely choreographed TikTok dances, they wear matching snug leotards, girlish rompers, curve-hugging Skims maxi dresses, and midriff-baring cartoon pajamas, sexy versions of the kinds of things young women lounge around in. (Only rarely do they appear in bikinis or lingerie; the risk of getting banned on TikTok is too high.) They make pouty faces and do trends in which they hop up and down and turn 90 degrees (the point being to watch their bodies bounce from multiple angles), or thrust their hands behind their backs to achieve the appearance of a torso that is nothing but curves. The audio in many of their videos is essentially cartoon sound effects, and much of what happens in them emphasizes their youth, from wearing Pokémon slippers and jumping on couches to feeding each other lollipops and playing water-bottle pranks. Paired with onesie pajamas, e-girl makeup on an already young-looking face, and the internet’s ideal waist-to-hip ratio, the effect is unsettling: In January, a viral TikTok described the group as a “grooming scandal” because “the deliberate marketing of youthful personas for adult content is creating a demand for barely legal performers.”

In between TikTok trends, the women stoke drama with other creators — some real, some fake — and boast about the money they bring in on OnlyFans. In a video from January, Araújo asks members how much they made the previous month; Rain replies that she’d earned $6 million, Sofey $2.5 million, Rose $1 million, Filippo $600,000, and Mei $100,000. The video serves multiple purposes: The eye-popping numbers make them seem aspirational (many of their comments come from women begging to be invited to the Bop House), undeserving (all they have to do is post sexy photos of themselves), or, worse, like a sign of the coming cultural apocalypse in which hot girls rule an army of lonely incels who pay for their penthouses and private jets. In other words, the Bop House thrives on rage bait, its content designed to piss off the same people it arouses.

By February, the Bop House had become big enough to inspire a slew of copycat OnlyFans houses — the Blonde House (for blondes), the Flophouse (for Brits), the Mini Bop House (for little people). With mainstream fame came the accompanying liabilities. “We’d get swatted, broken into, rocks being thrown, people docking their boats outside the house screaming at us. It was horrifying,” Araújo says of the three-month period when the Bop House rented a Fort Lauderdale Airbnb, until its owners kicked them out for the trouble their presence caused. At a second Fort Lauderdale location, while several of the women were on a private jet to the Super Bowl, a man claiming to be Rain’s fiancé broke in while another member was there; he was allegedly Rain’s stalker. The man was charged with unarmed burglary, resisting arrest, and using a false name. He pleaded no contest.

Among members, there is a divide between those who want to simply have fun and make money on OnlyFans and those who want to transcend the platform entirely. Its star, Rain, whose representative did not respond to multiple requests for comment, seems to fall in the former category. In July, Rain announced she was leaving the Bop House to spend more time on her farm in Tampa. “What started as an empowering space began to feel controlling, with certain members wanting to dictate how I should act, post, and live,” she wrote in a statement, adding, “Camilla and I were not getting along for a while, so I think it was just the best thing to do.” The internet responded in kind, with TikTokers celebrating the fact that the collective was “over.” “Since no one’s here to address it, I will be here to address it,” said Filippo in a video on July 18. “The Bop House is falling apart.”

But the dramatic exit seems to be part of a bit, part attention-grabbing and partly born out of the difficulty of wrangling a bunch of newly famous and increasingly wealthy influencers in the same place at the same time. The Bop House has always been built on illusions; it’s an idea, not a place, a fantasy where a bunch of hot young girls have a perpetual sleepover, even if none of them actually live there and none of them actually offer the kind of content their OnlyFans subscribers are hoping to see. Like all the most-talked-about influencers right now, the Bop House has mastered the art of the tease.

Filippo, left, and Araújo in Araújo’s Rolls-Royce.

Photo: Ashley Markle for New York Magazine

Though I had originally reached out this winter, it wasn’t until June that I finally got on the phone with a young guy named Connor, a publicist who told me the Bop House might be open to having a journalist come to Miami and see them in person. I was one of several interested reporters he’d spoken to that day, but the problem was that everyone was traveling and it was difficult to ensure they’d all be available at the same time. Over the next few weeks, the possibility of access dwindled: maybe it would be all the women, maybe it would be all the women except Rain, maybe it would only be a few of them. Ultimately, I only met two of its members, whom I first encounter at Araújo and Lynch’s brand-new, very white, still-empty home, which they bought in April for $5.2 million but have yet to fully move into. I arrive before they do, admiring the gated community’s population of wild peacocks, until a giant silver-chrome G-Wagon pulls up the driveway, emblazoned with neon-green letters spelling out “MainCharacter.com.” All three people who climb out of it embody the part: Araújo, with big hoops, stilettos, and a $2,000 pair of Jean Paul Gaultier black pin-striped trousers; Filippo in Adidas and a Dior saddlebag; and Lynch, owner of the G-Wagon (the website links to his social accounts) and a typical Gen-Z internet bro, hair flopping over his forehead, a gold chain and a tattoo of the words “BY ANY MEANS NECESSARY” over his forearm. They’re here to record the second episode of their podcast, Clock It, which they launched as a brand-building exercise, a way for their audience to get to know them as creators outside of the Bop House.

“I wish I was on this side! This is my good side! I want to sit like this!” cries Filippo as the two take their leather swivel chairs. “We’re not switching sides. I’m on my good-luck side,” replies Araújo with the exhaustion of an older sister even though they are the same age. Having met in high school in Raleigh, North Carolina, they bicker with the ease and the ruthlessness of hometown friends. “Technically,” Lynch pipes up from behind the camera, “if we’re talking statistics here, your most viral content has been with you on the other side.”

This is not a good enough reason for Araújo, despite more protests from Filippo. The argument descends into both of them accusing the other of lateness and then of being “fucking crazy.” Araújo turns to Filippo and says, “You know she’s writing this shit down?” referring to me. A moment later, they start recording. “What is up futher muckers, thank you so much for clocking in. We’re already arguing,” Araújo says. For the next hour, they rattle dizzyingly between topics, from the time a 9-year-old Araújo had a man pull up in a car and threaten to kidnap her at gunpoint to how she wants Cher to perform at her Great Gatsby–themed Christmas party (“Who’s Cher?” asks Filippo, and Araújo shows her the trailer for Burlesque). And they talk about the Bop House.

Araújo’s and Filippo’s entrance into the group came out of two fake beefs, one between Rain and Sofey, and another between Araújo and Filippo. “Sophie messaged me on social media and was like, ‘Do you wanna, like, low-key integrate this?’” Araujo tells me later as we’re sitting around her stark-white kitchen table. (Over the phone, Sofey offers up a different origin story: that the idea came when all the girls were having a sleepover.)

By the time she’d gotten the DM, Araújo had already built a social-media empire, first through a stint on MrBeast’s 2021 viral re-creation of Squid Games, from which she gained 146,000 Instagram followers in 24 hours, a number she can rattle off like trivia. But the real attention came from a series of engagement tactics, perfected with the help of Lynch. They’d post clips of Araújo on what looked like podcast sets, where she would say and do controversial things like questioning the value of college and traditional nine-to-five jobs, or interviewing her younger brother about what it’s like to have an older sister on OnlyFans, or very obviously scratching her genitals mid-conversation so that enough people would leave angry comments so she’d go viral. Filippo, meanwhile, was still in Raleigh and working at Top Golf when, in early 2024, Araújo said she could make her a millionaire. All she had to do was move to Miami, work as her assistant, and start an OnlyFans. “I’m like, ‘Listen, you don’t have to cross anything that would make you morally feel uncomfortable on that platform,’” Araújo recalls. “It truly is an illusion.”

Araújo knew that she could promise access to “uncensored” sex tapes and “fully nude content” on her OnlyFans page and put lines like “i promise it’s pink” in her social-media bio, as in the color of her vulva, even if subscribers would never be able to see it no matter how much they paid. Like the rest of the Bop House girls, the members’ pages are only slightly more suggestive than what they post on Instagram. In DMs and extra paid-for posts, where many OnlyFans models make the majority of their income, spicier content gets teased, but none of the Bop House girls do actual porn. “I’ve never done nudity, but I walk very fine on the line,” says Araújo. “I’ve learned many hacks and tricks and things like that.” Said tips and tricks she won’t tell me on the record, but the strategy worked for Filippo, too. After five months under Araújo’s tutelage, she’d made her first million on OnlyFans.

Araújo was also seen as the driving force behind some of the Bop House’s more controversial tactics. In February, she brought “TikTok’s worst mom” Ash Trevino to the house and grilled her in front of her teenage daughters. Filippo went on set with notorious porn star Bonnie Blue as she organized a gang-bang stunt; she told me the experience was “disgusting” and “traumatic,” even though it led her to making $600,000 in a month thanks to Blue’s fans following her on OnlyFans. The crew invited over 17-year-old influencer Piper Rockelle, who had previously joked that she’d join them on August 21, 2025, her 18th birthday. For one of the members, this was the final straw. “One thing about me is I’m never gonna do anything associated with a minor,” explained Joy Mei in a tearful TikTok at the time. Six months later, she tells me it was a buildup of other issues, too. “I didn’t have as high of a number of followers as some of the other girls, and because of that, I was kind of pushed to the side more,” says Mei, who went on to start a rival collective called the Asian House. “In the very beginning, it really was a friend type of thing and then ended up being more about the business and content, which is not what I necessarily signed up for.”

Araújo in her walk-in closet: “I’m trying to create a brand. I’m trying to create longevity. I want to be a billionaire.”

Photo: Ashley Markle for New York Magazine

The reason for this shift is not exactly a secret. “They were uncomfortable that I was treating it like a business,” says Araújo. Years earlier, she had dropped out of college and wrote two scripts for reality-TV shows and pitched them to networks, but they never got picked up. She felt she could develop a killer ensemble docuseries set at the Bop House. “We have a large group of girls and there’s a lot of drama all the time,” she says. “We’re gonna talk shit anyway. You might as well fucking monetize it.” In the spring, she wrote a pitch deck explaining who each of the members were and fed the girls guidelines on what they should say. She booked a jet and an Airbnb in Panama City Beach within three days and brought in a production team to film their every move: “And I let shit play out.”

They never filmed anything more than a sizzle reel. According to Araújo, the other girls were upset over the rushed timeline and complained about the Airbnb and the jet. And they didn’t like being treated as employees. Producers pitted the women against each other, which ended in a blowout more explosive than anything they’d been through before. When the producers showed the footage to Araújo, they all agreed they were seeing reality-TV gold, even though Araújo was aware that she’d been cast as the villain. They planned to start filming the full series and set a meeting with Peacock, when the other girls confronted Araújo about her behavior and decided they no longer wanted to be involved. “I think we realized we don’t blend well on certain aspects,” says Sofey. “If we have to create drama between us and always be mad at each other for drama for the show, it really just harms our friendship.”

“They just weren’t happy that I didn’t want to be friends,” Araújo says. “I can’t do business with people who don’t want to do business. I’m trying to create a brand. I’m trying to create longevity. I want to be a billionaire.” In the end, it was she who left them: Two weeks after I visited, Araújo announced on the podcast that she was officially exiting the Bop House, saying, “I was so over being blamed for everything.” Unlike Rain, she hasn’t appeared in any Bop House videos since.

One person who is almost never seen or mentioned in the Bop House’s social-media content but who looms over every part of it is a man named Joe. He manages Rain and Sofey and was instrumental in the creation and marketing of the Bop House, like the Angels’ titular Charlie. Though she doesn’t know his last name, Araújo describes him as “a genius,” having heard that he made his first million while still in high school through drop-shipping, or marketing products online from cheap wholesale platforms like AliExpress and selling them at a markup. Joe did not respond to multiple requests for an interview, but I meet him when Lynch drives us in the G-Wagon to the place I’ve been waiting to see all day: the current Bop House.

We pull up to a skyscraper in Brickell, Miami’s financial district, where two valets tell us we can’t park in the place we are definitely about to park. Lynch and Filippo lead me into the lobby while Araújo mans the car in case the valets cause us any trouble. They’ve chosen this place because unlike the Fort Lauderdale Airbnb, nobody can break in or dock their boat outside to jeer at them. All visitors must pass through a heavily guarded glass doorway to get to the elevator banks, and no one is allowed to sit in or film inside the lobby. The elevator takes us to the penthouse floor, the 62nd, and the man who greets us inside is the mysterious Joe, blond, polite, quiet, and, like the Bop House girls, looking younger than his age, which is 24. The penthouse is his, apparently, a $100,000-per-month rental with three stories, an elevator, and extremely tall ceilings. Everything is gray and spotless, with the exception of giant rainbow light-up letters that spell out “BOPS.” Filippo leads me to the rooftop, which has a pool and nearly 365-degree views of the Miami skyline, which glitters black against the pink-and-orange sky. We can’t stay for long — Araújo is texting Lynch furiously that the valets are currently knocking on the window and demanding she move the car.

The sun sets as we ride around in the G-Wagon, which I discover is one of several silver chrome “Main Character” luxury cars in Lynch’s collection. We pass by a group of teenage boys filming TikToks; like almost everyone else on the street, they crane their necks to see what’s written on the side of it. While Araújo is busy trying to organize a photo op with Chris Brown for an upcoming LIV nightclub performance, Lynch tells me about a few more of his strategies for getting rich online. Clip farming, in which anyone can take particularly attention-grabbing clips from podcasts or livestreams and pump them out on short-form video feeds, is chief among them. He runs a Discord server where around a thousand people from all over the world take moments from Filippo’s livestreams and repost them on their own channels, paying them $30 per 100,000 views their videos get. “You can make good money even in the U.S. doing that,” he explains. “There are people who do this and make ten, twenty thousand a month, just kids in high school.” OnlyFans is only a portion of their income; Araújo and Lynch also own 12 properties across Florida, Mississippi, and Ohio, some of them Airbnbs, some of them Section 8 housing with live-in tenants.

A lot of what gets clip-farmed happens to be rage bait or just straight-up lies. Araújo, for instance, tells me that, despite claiming to, she never actually shit in a jar for $50,000. (“If I did, it would be a fucking M for me to do it,” she says, by which she means a million dollars.) Filippo never actually broke into Araújo’s house and stole her dogs, which they sheepishly admitted on Clock It. “Everything was fake. Everything,” she says. “Oh my God, I have the chills, because we haven’t told anyone that. Do you think we’re gonna get hate?” Recently, there was a rumor one of the Bop House girls is pregnant. “I was just making up things,” says Araújo, laughing. The braces several members wear aren’t strictly necessary, either, at least according to Mei. “I get you need braces sometimes, but three years?” she said in a video. (Sofey tells me she got so much hate for her braces that she removed hers and now wears Invisalign.) The reason many of them wear Spider-Man costumes is because of a yearslong engagement-bait hoax in which an alleged porn clip showed a woman who looked like Rain having sex in a Spider-Man costume.

Even the Bop House being “over” is its own kind of lie; in the weeks since Rain announced she left, she’s posted a slew of videos with the other girls and traveled with them to Los Angeles, where on August 8, the Bop House held auditions to replace its most famous member. They landed on Lexi Marvel, an OnlyFans creator who had previously gone viral for her striking resemblance to Rain. They plan to take a trip to the Bahamas together soon and are looking into opening an L.A. Bop House to be closer to the heart of the influencer industry. By the time I ask Araújo whether Rain and Sofey are actually cousins, I am fairly certain of the answer before she says that it was, of course, all made up. “I think they’re dropping that. They’re not really trying to hide that anymore,” she says, though when I talk to Sofey on the phone weeks later, she claims otherwise. “We grew up together; we went to the same schools,” she says, “Our moms are Filipina.”

There’s one aspect of Bop House criticism that both Araújo and Filippo say they’re sympathetic to. Early on, TikTokers and their commenters accused them of making content for pedophiles. “That’s how I blew up, because men loved how innocent I looked,” says Filippo. When I ask how she feels about that, she replies, “Disgusting. It’s sad. It’s horrible.” In one of their earliest viral videos together, Araújo asks Filippo how much money she made in her first week on OnlyFans ($54,000). “Y’all are sick fucks, ’cause she looks 12,” Araújo scolds the viewers. Araújo and Filippo both feel shame about their work for this reason; though Filippo grew up as a “hot Cheetos girl” and a staunch atheist, she found God at a low moment in 2021 and now goes to a church nearby. “Doing OnlyFans, I struggle with my faith every day. I’m proud of who I’ve become and who I am, but the act of doing it, I’m not proud of,” says Araújo, who is also religious. “It’s the hardest part.”

When you’re talking to professional influencers whose popularity hinges on generating attention by any means necessary, the sincerity of the things they say is always in question. Though none of the Bop House members I spoke to admitted to deliberately making themselves appear younger, it would be naïve to assume they don’t know the power it has given them. The Bop House members didn’t invent the concept of barely legal fantasies, nor are they the only women who have made millions from looking like sexy babies. To admit that the aesthetic is intentional, however, would be to shatter another illusion: that they are simply normal girls hanging out and having fun. “For some reason, people don’t like to see young girls be successful, and they always try to find something to nitpick or make them look worse,” says Sofey. “It’s a hard industry to be in to thrive and do well and have everyone’s support.”

Araújo and Filippo are not on OnlyFans because they love sex. Money is what brought them there — both grew up poor, Araújo to Brazilian immigrants, Filippo to a single mother with whom she lived in “like 13 different houses.” Araújo now supports her parents, who have been able to retire, and put her brother through college. In Brazil, she set up an OnlyFans page from which the proceeds go entirely to her extended family still living there. Strangers seek help from them, too. “We play a game where we say, ‘Try finding a DM where someone’s not asking for money,’” she says, before Filippo adds, “You can’t.”

Filippo and Araújo with young fans at a café in Miami.

Photo: Rebecca Jennings/New York Magazine

And then there are the little girls. Recently, an audio went viral on TikTok of middle-school-age girls in Australia talking about how the Bop House has affected the way boys at school treat them. The original video was recorded by the anti-pornography activist Melinda Tankard Reist, who interviewed seventh-graders in Far North Queensland. “They expect us to be like the Bop House,” one can be heard saying. “They expect us to do the types of things that they do.” Though I had planned to ask Filippo and Araújo about how they felt about this, they address the controversy on Clock It while I’m in the room. “If their parents deem it inappropriate, then they have all right to block us and move on. But these little girls, I’m not promoting anything provocative to them on TikTok,” says Araújo. “Everyone thinks that we are out here doing what we do to promote it to younger crowds, which is so messed up because that’s just not our objective at all,” adds Filippo. “That is disgusting.”

This demographic is a newer one for the Bop House women. Before, Mei says her following was mostly men, but since she joined the Bop House, it’s closer to a 50-50 split. “It’s a lot of girls, I’m not gonna lie,” she says. “I feel like a lot of girls come up to me, and I’m just like, ‘Wow, I love you guys so much, you guys are so cute.’” Araújo’s followers, too, have shifted from around 96 percent men to 69 percent women. The change, she says, is due to TikTok, where her content tends to be more PG than on Instagram due to its restrictions. “TikTok does not convert to OnlyFans at all,” she explains, citing the fact that the platform doesn’t allow users to include links in their bios that link to OnlyFans. She says the Bop House women use TikTok to stay relevant, but that going viral there doesn’t translate into money. What it has given them are legions of teen-girl fans who discovered them on TikTok, then trickled into Instagram, where Araújo now has 5.4 million followers.

After the Target run, the gang grabs strawberry-matcha iced lattes at a café a few minutes away. As they enter, a handful of patrons immediately do the thing everyone does when there are famous people present, which is to take photos in a way that is meant to be sneaky but is painfully obvious to everyone around them. Most of them are women in their 20s and 30s, but one group sitting at the counter doesn’t seem to take notice. They are a mother and three girls, two around middle-school age and a younger sister no more than 8 or 9. As the group gets up to leave, the mother approaches our table to ask for a photo. The three girls pose with Araújo and Filippo, looking simultaneously sheepish and thrilled. I’m reminded that this, in fact, is what actual 12-year-olds look like. As they leave, Araújo looks back at them as if she almost can’t believe it, shrieking, “You’re so cute!”

One Great Story: A Nightly Newsletter for the Best of New York

The one story you shouldn’t miss today, selected by New York’s editors.

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice

Related