Critic’s Picks: Books of the Summer

4 Columns

Philosophy, case study, biography, fiction: four newly published

page-turners to add to your bookshelf.

As the dog days of summer wind down to an end and we brace for September, four critics reflect on their favorite books of the estival season. While there’s not a traditional “beach read” in the bunch, each pick is ripe for rich reflection on the complexity of human experience, ranging from deliberations on love (and its works), wildness versus “civility,” writerly inspiration and dedication, and the fleeting beauty of the small details of life set against the looming specter of death.

• • •

Works of Love, by Søren Kierkegaard, translated by Bruce H. Kirmmse, Liveright, 430 pages, $35.99

Reviewed by Ania Szremski

We can never know where love comes from—it’s something we have to believe in, but also have to live (and it’s only in giving it that it’s knowable). Love exists before and after the lover loves. And love does not belong to the lover, but to the beloved—in the deepest form of love, the lover disappears.

These are just a few of the proclamations on love in Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard’s Works of Love, first published in 1847, in between his arguably more famous tracts on anxiety (The Concept of Anxiety, 1844) and despair (The Sickness unto Death, 1849). Connecticut College professor and Kierkegaard scholar Bruce H. Kirmmse has just published a capacious, generous, and lyrical new translation of this two-part series of “deliberations,” a translation that, like the original, is meant to be read aloud. (This accounts for Kierkegaard’s somewhat idiosyncratic use of punctuation, which Kirmmse has tried his best to respect the spirit of here.) Works of Love is not exactly a beach read, yet for me it was the perfect book for a summer of hate. If in some ways it’s a dense and hefty tome, it’s also sonorous in its melodies and enthralling, paradigm-shifting in its propositions—I don’t know if scholars would agree, but I think it’s fair enough to treat this as a volume to dip in and out of, flipping between chapters, when the mind is calm enough for reflection, to find hope, respite, lessons for living a different kind of world.

Crucially, for instance: in the same way that reality-rending events, like catastrophes, can disorient ideas of self and other—so with love. Love is an event like that. Love is transformation. “Love is a revolution; the most profound of all . . . a revolution from the ground up.”

• • •

The Forbidden Experiment: The Story of the Wild Boy of Aveyron, by Roger Shattuck, introduction by Jed Perl, New York Review Books,

220 pages, $17.95

Reviewed by Brian Dillon

On January 9, 1800, a disheveled boy of eleven or twelve, dressed only in the remnants of a shirt, was discovered digging up vegetables in a garden in the southern French department of Aveyron. It seemed he could not speak or understand others’ speech. He relieved himself where he stood, and paid attention to his surroundings only when hungry: given a choice, he ate mostly potatoes. “The wild boy of Aveyron” fascinated postrevolutionary France, where his apparent state of nature tested ideas about innocence and experience, the vicious or improving role of society, and the innateness (or not) of language and meaning. Victor (as he became known) was transported to Paris and housed near the Sorbonne at the Institute for Deaf-Mutes. There, he was at first neglected, then carefully studied, instructed, and eventually given up on as a failed experiment. He died of pneumonia in 1828, still in the care of his institutional governess, Madame Guérin.

The critic and scholar Roger Shattuck (1923–2005) is best known for his writings on Proust and for The Banquet Years, his 1958 study on the origins of the Parisian avant-garde. The Forbidden Experiment was first published in 1980; this new edition comes with an affectionate introduction by art critic Jed Perl. Shattuck tells a compelling story—centered on the boy’s encounter with a young doctor, Jean Marc Gaspard Itard, who tried to educate him—which is mainly intriguing and instructive for the large philosophical and moral questions the case raised. Nature versus nurture, Descartes contra Locke, Hobbes against Rousseau: much that vexed the Enlightenment is contained in the tale of this inexplicable child. But Shattuck asks more human questions, too. Would the wild boy have been happier, possessed more purpose, surviving in the woods instead of trying and failing to satisfy his civilized captors? Echoes of Shakespeare’s Caliban: “The red plague rid you / For learning me your language!”

• • •

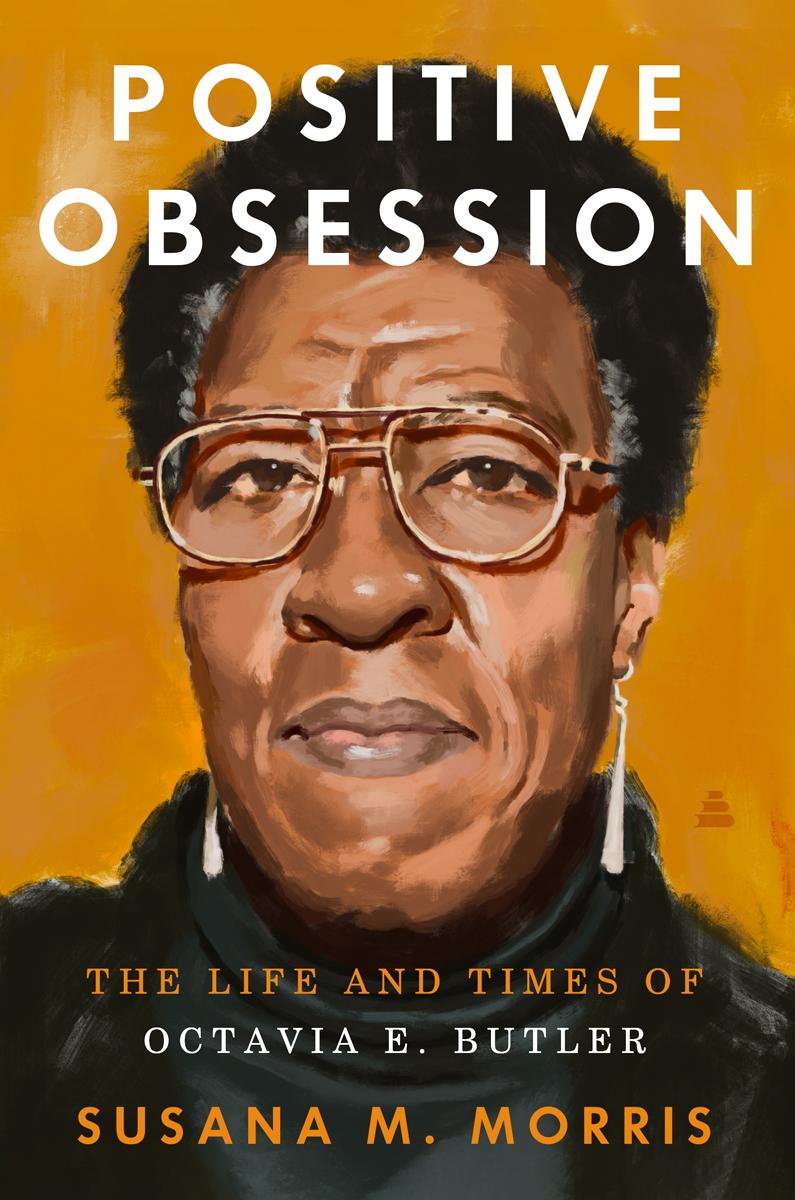

Positive Obsession: The Life and Times of Octavia E. Butler, by Susana M. Morris, Amistad, 247 pages, $29.99

Reviewed by Julie Phillips

A fortunate fate awaits scholars of Octavia E. Butler. Already admirers of her Patternist and Xenogenesis series, her visionary Parable of the Sower, her late “ethnogothic” vampire novel Fledgling, and her prescient essays, they go to her archives, encounter her notebooks, letters, and journals, and fall in love. They meet a woman who is solitary, yearning, visionary, and burning with the stories she wants to write, about “futures with Black women at the center.” She struggles to put her vision into words, fighting self-doubt with the futurity of positive thinking (“My books will be read by millions of people! So be it! See to it!” she insisted), while also urging herself to use her research to “make people touch and taste and know. Make people FEEL! FEEL! FEEL!”

Good books keep coming out of these archives: a short bio by Lynell George, a monograph by Gerry Canavan, and now Positive Obsession, the first full biography. Its author, Susana M. Morris, an academic and cofounder of the Crunk Feminist Collective, emphasizes Butler’s determination to write, despite her lack of money and models. (Born in 1947, she didn’t encounter the work of Black women writers until college.) Morris also, invaluably, traces the connections between Butler’s life and her fiction, exploring the personal, political, and historical context and the hands-on research that shaped such an influential vision and voice. She takes inspiration from Butler’s self-affirmation and relentless drive, as well as from her glimpses of a more just world in which neither would be necessary.

Focusing on the work, she skims the later years, when Butler’s health declined and she wrote less. My only wish for this empathetic and insightful biography is that it were longer, so I could spend more time in Butler’s, and Morris’s, company.

• • •

Such Times, by Christopher Coe, Archway Editions, 351 pages, $16.95

Reviewed by Jeremy Lybarger

Christopher Coe published two novels before his death from AIDS-related complications in 1994. The first, I Look Divine (1987), is a Wildean oddity: a svelte tale of a narcissist’s fatal infatuation with beauty, tinged with would-be incest and a cloying dandyism that can only be described as faggy. His second, Such Times (1993), newly reissued by Archway Editions, demonstrates how much Coe ripened as a novelist in that six-year interregnum. To my mind, the book stands alongside those of Andrew Holleran, Alan Hollinghurst, Edmund White, and other recent grande dames.

The plot is simple: Timothy Springer has an older lover, Jasper, who is also in a long-term relationship with another man with whom he lives in mortgaged and sexless civility. Timothy and Jasper’s affair plays out in a kind of bourgeois bell jar: posh restaurants, fussy booze, a pied-à-terre in Paris, every last thing aestheticized into a moral injunction. Timothy is a connoisseur of fleeting delicacies: “What is lovelier than tall green stems, cut on the diagonal near their base, standing in clear water, in a clear glass vase?” Then AIDS, an erstwhile bit player, becomes the novel’s annihilating star.

Such Times is the story of a relationship undone by the virus, during a period in American life when the cost of loving “without demands” too often proved deadly. Coe’s work is a requiem for heedless pleasure, for the brevity of cut stems or the pathos of cruising: “There is something that will always be endearing, almost heartbreaking to me, about naked men standing around together in nothing but their shoes.”

Philosophy, case study, biography, fiction: four newly published page-turners to add to your bookshelf.