Krupa Ge’s newest novel, Burns Boy, starts on a sinister note – a 15-year-old boy lies all wound up in a hospital burns ward. He’s the only male in a female-dominated room – women burnt because of dowry harassments, or by jilted lovers, or those who have who set themselves on fire to end their miserable lives. It creates a rip in the universe when Guru ends up there. How did a boy, so young at that, get licked by the flame?

Guru’s angst, which at first feels like a symptom of his teenage, is thoroughly directed at his mother. He’s angry with her for not saving him in time, for “showing off” her good health, and blames her for the father who’s never home. His mother claims she’s always at the hospital, but he barely sees her either. “She was overly friendly with everyone but her children,” grumbles Guru. And now, he’s convinced that his mother wants him dead – the fire could not kill him, but her apathy just might.

His younger sister Aparna is more of a roommate than a confidante. She drops in with her mother, but there is no real camaraderie between the siblings. Each seems to hanker for the mother’s attention while resenting her in their own unique ways.

With or without

What of the mother, then? An assistant clerk, she prides herself on having a government job. She can look after herself, her children, and her elderly mother. She is always hot and bothered – the blistering heat of Chennai and two surly children make matters worse. She’s not blind to their resentment: “If you cannot bear the thought of someone hating you for some time, if not most times, I suggest not having kids at all.”

She recalls the early days with her babies, a time of great suffering and reluctant sacrifices. But unlike babies who have no memory, the mother bears her in silence, broken and beaten by circumstances that simply seem beyond control. The absence of these memories, Ge writes, is “the [mother’s] curse and the [child’s] blessing.” When the mother relives memories of wanting to be run over by a bus so that she could slip into “eternal sleep”, one suspects that this is more than just postpartum exhaustion.

The mother’s route to this moment has been long, convoluted, and extraordinary. The stuff of royal scandals for any Indian town, she matter-of-factly recalls how she met her “husband” and the conventions she defied to have the life she wanted. There is something to be said about her own mother, who, though privately disapproving, stood by her daughter when no one else did. However, what the mother considers a happy marriage, the couple comfortable with the silence and distance between them, is judged harshly by the children.

At 15, Guru is somewhat wise to the ways of the world – he lashes out at his sister for discovering his secrets and spares no opportunity to insult his mother. In his eyes, his mother is his father’s “second something”, and she has forced him into a “gross, indecent arrangement.” Both times he brings up the women’s “honour”, fully aware of the word’s loadedness, and in the process, budding into a misogynist.

In this house

While Guru burns in anger and bitterness, his sister stews in neglect. She is “stranded” with nobody on her side – her mother has her absent father, and Guru has their ever-present grandmother. Love and acceptance are scarce in their house. The grandmother is fearful of the father abandoning them, the mother does not know her children, and the two young siblings live in a constant state of shame. This arrangement, which helps nobody, imposes on the children that they are “weird” and certainly “immoral”, and definitively concluding that the father was the “originator” of the group’s shame.

The mother too exists in a dual state – harassed by her children yet fiercely independent in her desires. A prolific writer, everything in life finds its way into her stories. Not cowed down by age or her judgmental children, she decides to mend things with her past – resulting in monumental consequences.

Burns Boy observes the debilitating effects of time and ageing on familial discord. Adulthood does little to salvage Guru and Aparna’s pains, nor does it make them sympathetic to their mother’s hardship. The antipathy is deeply set by the time they leave home, carrying with them memories of shame, neglect, and heartache. In this house, there is neither forgiveness nor reconciliation.

Ge is fierce in her construction of a family hurtling at a dangerous speed to end up where it should strictly avoid going. The mother’s revelation is discomfiting, the boy’s anger is unsettling, and the girl’s indifference is worrying. Every moment, something threatens to break, for the harshest words to tumble out. Ge precisely depicts the cruelty of children – their painfully unforgiving scrutiny and blistering castigation.

In addition to the suffering of children in broken homes and unhappy marriages, Burns Boy also tries to understand how children, often unforgiving of mistakes, are indifferent to the parents’ grief. The fall of the authority figure also disrupts a child’s understanding of the family unit, its hierarchy – and instead of allowing the child to see the parent as an equal (which is possible in happy circumstances), creates a chasm that can neither be filled by filial love nor duty. So, when the mother cannot discipline her children into loving her and when the children do not fear hating the mother, what then remains of this essential bond? Burns Boy, with great nuance, attempts to answer this difficult question.

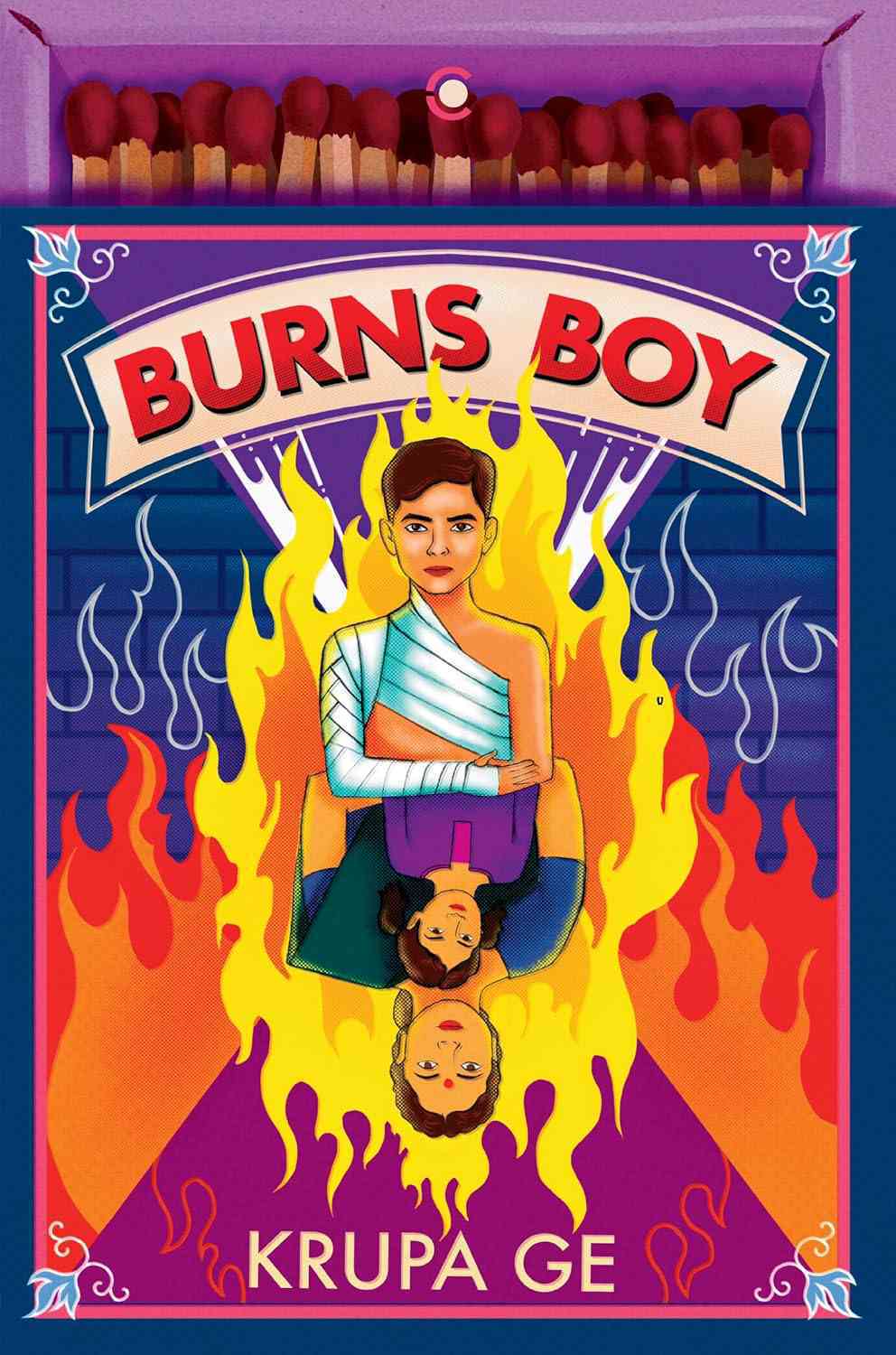

Burns Boy, Krupa Ge, Context/Westland.