A few headlines around today are saying similar things about the likelihood that Labor won’t hit its national housing target.

It’s interesting to see these types of headlines on stories that don’t consider similar periods from history.

If we turn our minds back to the post-WWII war period, when the Curtin and Chifley governments announced a mass home-building program, they too were ridiculed for their overly ambitious “plan” and for missing their “targets” in the early years of the program.

You can get a taste of those criticisms by reading newspapers from that period.

For example, in June 1946, the leader of the Country Party, Arthur Fadden (in opposition at the time), was quoted as saying this about the Labor government’s post-war housing program:

“The government planners set a target of the number of homes which should be built in the ensuing year. This does not really ensure that the particular number of houses will be built. It merely gives the experts something to plan about,” he said.

“The actual building must be done either by another department, or by private builders, or by ex-servicemen with their own hands or by some other means.

“On the basis of the 1945-46 target, of 24,000 homes, the shortage will take about a generation to overcome.

“In the first half of the year, only 192 houses were completed by the government’s efforts in Queensland, and 1,791 in Australia. The large gap between planning and production is not confined to Queensland. In New South Wales, the figures are equally depressing.

“Buildings completed in 1945 total only one quarter of the number built in 1917, the worst year of the First World War.

“The War Service Homes Commission was established to look after the housing needs of ex-servicemen.

“Yet, for the year ended June 30, 1945, the commission had completed eight houses throughout Australia.

“At this rate, it would take about 10,000 years to cover the housing needs of ex-servicemen.

Fadden went on:

“Stock excuses have been advanced: first, the dearth of skilled tradesmen, secondly, a scarcity of building materials, then the prevailing high cost levels.

“The homeless citizen does not want excuses — he wants a home. The ex-serviceman does not want explanations —he wants action.

“The Labor government has proved itself incapable of providing the action, which will result in a greatly increased number of houses in a relatively short period,” he said.

Of course, that post-war housing program was plagued by problems in its early years.

That’s because it took time for Australia to shift back from a wartime economy to a peacetime economy. So, it did suffer a dearth of builders and building materials at the beginning.

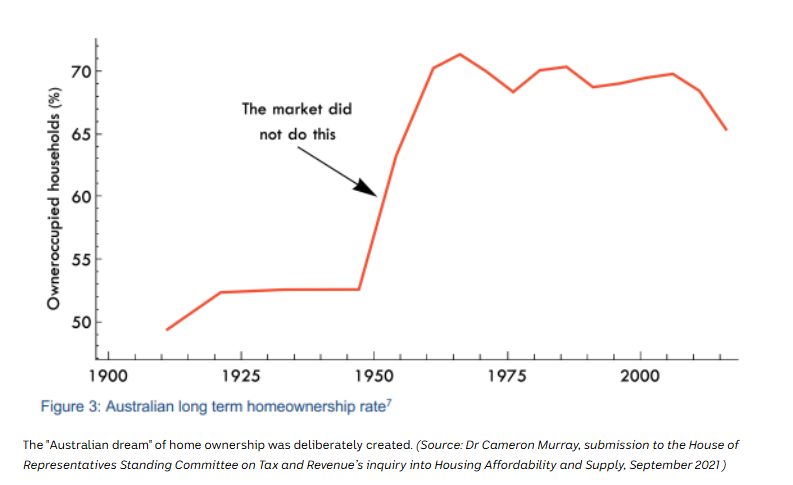

But eventually things got going. More houses started to be built. And it led to a surge in owner-occupiers and the creation of the “Australian dream” of widespread homeownership.

Could that have happened without having an ambitious housing “plan” and home-building “targets”?

Part of the point of setting a target is to be held to account to that target, which keeps everyone’s attention focused on the end goal.

Will the Albanese government’s housing “target” eventually lead to the necessary number of homes being built in the long run, proving today’s naysayers wrong?

Or will today’s naysayers be proved right in the long run?