By JULIE CARLE

BG Independent News

Artist Norman Rockwell is known for portraying Americans as Americans chose to see themselves. His iconic magazine covers and artwork were filled with familiar details that helped to tell stories of everyday life.

Kelleigh Bossa, a longtime Perrysburg photographer who has only recently discovered art beyond the lens, has a similar purpose in her latest project that she calls “Not A Rockwell.”

Kelleigh Bossa uses her artwork to fight injustice and give a platform to others who have been silenced.

Kelleigh Bossa uses her artwork to fight injustice and give a platform to others who have been silenced.

Bossa described herself as an “artistic housewife,” who experienced religious abuse as a child and was forced to be quiet and not allowed to express her own feelings or ideas. Her recent work, including the “Not A Rockwell” series, represented her finding her voice and using her art to fight injustice and give a platform to others who have been silenced.

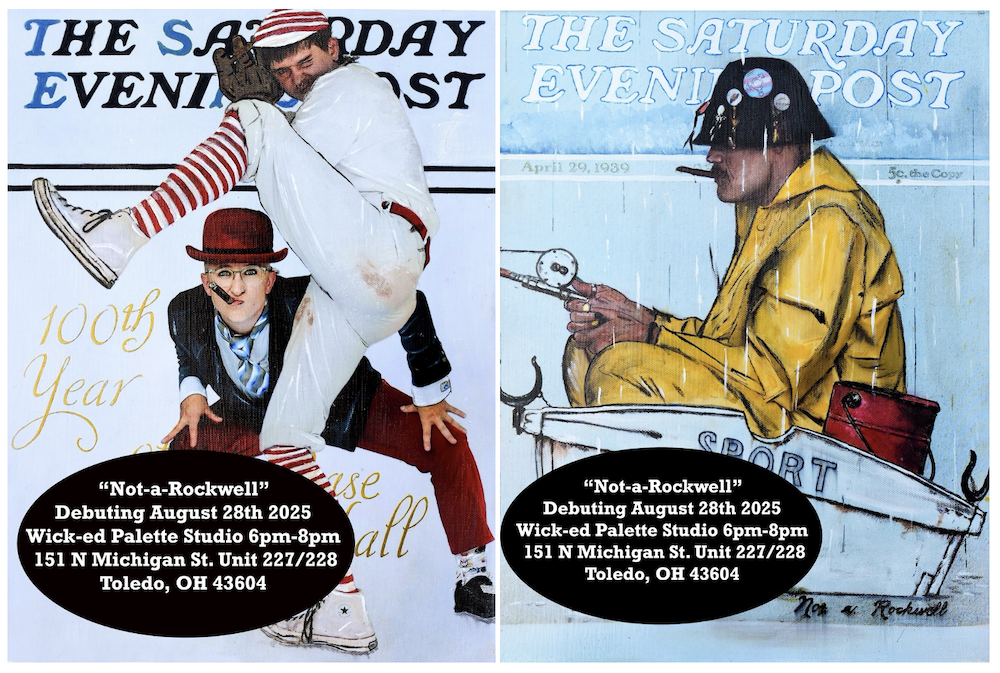

For her “Not A Rockwell” series, Bossa used some of Rockwell’s recognizable images to create the 17-piece collection that tells the stories of local people who identify as LGBTQ+, Black, Indigenous and People of Color. The artwork is “a direct response to the current political climate and dehumanizing rhetoric aimed at the LGBTQ+ and BIPOC communities,” she said.

“Not A Rockwell” is one of Bossa’s three collections that will be exhibited from 6 to 8 p.m. on Thursday (Aug. 28) at Wick-ed Palette Studio, 151 N. Michigan Ave., Unit 227-228, Toledo. Bossa created 14 of the 17 pieces; Susan Dunn, an art colleague, added three pieces for the collection.

Two of the art pieces in Bossa’s “Not A Rockwell” collection.

Two of the art pieces in Bossa’s “Not A Rockwell” collection.

The project grew rapidly from a single idea to 17 pieces in just six weeks. She first shared the idea with Alan Dow, a transgender non-binary who owns the House of Dow in Toledo. He loved the idea, agreed to participate and offered full access to his store’s vintage collections to style the individuals for Bossa’s artwork. The scope of the project mushroomed after he provided suggestions for other models and venues, and those models had additional ideas.

“The entire cast is LGBTQ or BIPOC, which is not what you generally see in Rockwell’s art,” she said.

Each individual put their heart and soul into the project, and they were powerful in their own way.

A transgender woman, Bobbie, was one of the original models for the concept. Bossa first saw her at an event where she was sort of hiding in the corner. “And I am NOT the person that lets anyone hide in the corner if it looks like they don’t want to be there,” she said.

Ultimately, she became the face of “Bobie the Baddie,” reimagined from Rockwell’s “Rosie the Riveter.”

Bossa left the original dates on the artwork. The “Rosie the Riveter”magazine cover was from 1943, and it mentions the atrocities in Germany at the time.

The “Bobbie the Baddie” artwork mentions the American atrocities of today “and instead of concentration camps, we have our own version with Alligator Alcatraz. It’s so similar, it’s terrifying,” she said.

Another model was a gay man who described his childhood as “a puppy being held down by the throat for 18 years.” And there were others whose stories Bossa shared in Rockwell style for the “Not A Rockwell” collection.

Bossa’s artwork tells stories of today’s marginalized populations.

Bossa’s artwork tells stories of today’s marginalized populations.

Bossa was honored to give Bobbie and others a platform to be able to feel themselves and feel confident in the person they’re being, in a world that tries to make them small or go away

“That’s what makes me feel good about this,” she said. Helping these people feel like they belonged was important and one of the reasons for doing the project, but she admitted there was a bigger reason.

“Rockwell hits with a very specific demographic, and that demographic tends to follow the rhetoric that these humans don’t matter, that their lives don’t have value, and they shouldn’t be included, or be celebrated, or even be here,” Bossa explained.

That is the demographic she wants to impact. She wants them to have “at least one moment in their brain that will humanize folks who aren’t exactly like them.”

In the short time she has been promoting the Thursday night exhibition, she’s seen it play out. They will see the artwork, which makes them think fondly of Rockwell’s work. Once they look closer and realize it’s not what they thought, their faces changed.

“That’s the point I live for—that one connection point,” Bossa said. “They don’t have to change their mind or be a different person after they see it, but they got that one second of thought where they loved that image and celebrated it and emotionally connected to it until they realized it wasn’t somebody like them.”

She sees that millisecond of a connection as a way “to help humanize the humans who are being dehumanized.”

“I was happy to be the right person in the right spot at the right time to help all of these amazing humans have a platform to share who they are in a positive light and in a world where they’re being forced to hide or feel like they shouldn’t exist at all,” Bossa said.

Putting the collection together

For the project, Bossa photographed individuals who identify as LGBTQ+ or BIPOC, placed them into the Rockwell background using Photoshop, and reworked the scene to make them fit, she explained.

When the image was complete, she had the photograph printed on canvas. Once she received the printed canvas, she painted on it to complete the Rockwell aesthetic. “It was really cool to incorporate so many aspects of art that I’ve been playing and practicing with and to put it all into one piece,” she said.

A week into the process, “I realized that this has nothing to do with me anymore. I’m just a conduit,” she said. “I had a cool idea, and I’ll own that, but this project is destined to be in the world, right now.”

Art is a critical tool for fighting social injustice and humanizing marginalized people. Reinterpreting iconic American art was “a uniquely effective strategy to challenge the ingrained prejudices of the specific demographic that cherishes that art,” she said.

“Every individual has a moral obligation to use whatever tools they possess to stand up against hate and dehumanization,” she said. “It’s not going to be on me, because I’m going to fight with everything I have, which is not a gun, and it’s not a knife. It’s a paintbrush and a camera, but it’s what I have and what I can fight with.

Posted by: Julie Carle on August 26, 2025.

Last revised by: David Dupont