The intense interest in Major League Baseball expansion and realignment last week surprised those inside the league office in New York. What commissioner Rob Manfred said publicly on the subject had lasted just 52 seconds, and none of it was new information.

But the expansion conversation captivates, and now that there’s resolution in sight for the two items Manfred has long cited as expansion roadblocks — the uncertain futures of the Athletics and Tampa Bay Rays — it no longer feels premature to raise the topic. Nowhere is the spike in interest more apparent than in the cities vying for a spot when MLB expands to 32 clubs.

“There’s tremendous excitement locally about the potential for expansion,” said Steve Starks, CEO of the Larry H. Miller Company in Salt Lake City, describing the market as “buzzing with anticipation” about the prospect of bringing the big leagues to Utah.

In recent weeks, The Athletic sought progress reports from six cities with established expansion efforts underway — Nashville, Raleigh and Orlando in the east; Salt Lake City, Portland and Austin in the west — about their latest updates and current priorities. Though Nashville and Salt Lake City are considered frontrunners by many in the industry, Manfred said last month the league has made “no pre-determinations” about locations. Taking the commissioner at his word, there’s still a chance one of the next expansion clubs will wind up in Montreal, Charlotte, San Jose, Vancouver or even Oakland.

Manfred intends to have two new teams selected before he retires in 2029, but it’s unclear when the league will begin the formal expansion process and consider each city’s bid. Elements of expansion will need to be negotiated in the next Collective Bargaining Agreement; the current one expires Dec. 1, 2026. Another unknown is the expansion fee. Most groups working on building expansion bids project it will be between $2-2.5 billion.

Even if the expansion teams won’t take the field until the 2030s, there is a sense of urgency to lock in potential stadium sites. “These are real estate deals,” said John Loar, managing director of Music City Baseball in Nashville, and getting three years ahead of expansion is “an absolute requirement” to build a ballpark and surrounding mixed-use development. (Many prospective stakeholders are looking to replicate a complex like Atlanta’s The Battery.)

“It’s a marathon,” Loar said, “but you sort of have to take a sprinter’s approach.”

EastNashville

General partnerStadium SitePublic funding for ballpark

TBA

TBA

TBA

When The Athletic polled MLB players in 2023 about the best potential expansion city, 69 percent selected Nashville. The Tennessee capital already has a strong baseball scene thanks to a Triple-A team and SEC powerhouse Vanderbilt University within city limits, as well as a proven track record of supporting its pro sports teams.

“I think Nashville is kind of a no-brainer,” Loar said.

Music City Baseball has spent years building the brand and story of the Nashville Stars — a name borrowed from the city’s Negro league team — and positioning itself as the most natural fit to be MLB’s next team in the east. But at this stage, the group is still missing some critical components of a bid, including a general partner and a stadium site.

(Rendering courtesy of Music City Baseball)

Loar said the group will focus on finalizing the ownership group later in the process, once the expansion fee is known. “There are some obvious choices here,” he said, “people we keep informed that need to help facilitate it.” That’s a lesser priority at this point than picking a ballpark location. “If you don’t solve the real estate, the location, and figure out how to get a world-class entertainment (venue) and ballpark shovel-ready,” Loar said, “none of that matters.”

After partnering with real estate firm Lincoln Property Company and development company Mortenson, Music City Baseball has targeted two sites in Davidson County as possible locations for a ballpark and surrounding mixed-use development. Loar said one site is more connected to downtown, while the other is “on the right side of the river connected to downtown.” The right location “affects the brand of baseball,” Loar added, and because of the importance of getting three years ahead of expansion on the real estate front, he’d like to have the site selected by 2026.

That makes this an important time for Music City Baseball, even if formal expansion talks aren’t yet in sight.

“Every day, every year is critical,” Loar said.

Orlando

General partnerStadium SitePublic funding for ballpark

Rick Workman

Southwest Orlando

TBA

When the late Pat Williams, who’d already helped bring Orlando one expansion team (the NBA’s Magic), first spoke with Jim Schnorf about leading the effort to land an MLB franchise, Schnorf told him, “The issue will not be whether I can arrange the capital. It’s going to be getting the right stadium site and the right control owners, hopefully, that have a connection with and passion for Orlando.”

Schnorf, now chief operations officer for the Orlando City Baseball Dreamers, claims to have checked each of those boxes. The group’s control ownership includes Rick Workman, a former dentist who founded a dental management company, and John Morgan, founder of a personal injury law firm. The Dreamers have announced more than $3 billion in total funding toward an expansion fee and the club’s portion of stadium costs.

(Rendering courtesy of the Orlando Dreamers)

The Dreamers’ preferred site for their proposed 45,000-seat domed ballpark is in a tourist district in southwest Orlando, close to theme parks, a convention center and plenty of hotels and restaurants. Because of that, Orlando, unlike other potential expansion cities, would not plan a large area of mixed-use development around the ballpark.

While MLB may be wary of adding a third Florida market, the possibility remains that the Rays will not stay in the Tampa area long-term. In recent months, with the Rays sale pending, the Dreamers have made it clear that they see Orlando as a solution should any MLB ownership group decide to move their club.

“We think we’ve got a number of swings,” Schnorf said, “and we’re very, very confident — because we are in such a leading position in terms of our market and progress — one of these paths will generate a Major League Baseball franchise for Orlando this decade.”

Raleigh

General partnerStadium SitePublic funding for ballpark

Tom Dundon

TBA

TBA

When Tom Dundon is willing to put his financial might behind a project, it should be taken seriously. Dundon, owner of the NHL’s Carolina Hurricanes, is part of a group poised to purchase the NBA’s Portland Trail Blazers for $4.25 billion. Yet Dundon remains interested in bringing MLB to North Carolina.

“Tom has publicly indicated that he’s very interested in owning a Major League Baseball team,” Hurricanes CEO Brian Fork said. “He thinks Raleigh would be a great market to have it, and is interested in taking the steps necessary to try to make that happen.”

At this stage, Fork and Co. are brainstorming stadium sites, modeling sponsorship and ticket sales figures, and communicating with local and state officials and business leaders in the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill triangle. Reception, Fork said, has been “universally positive.”

“We’re trying to stay ready, do the homework we need and do the planning we can do … so we’re ready to act whenever (MLB) gives the go-ahead,” Fork said.

While Charlotte is another potential expansion city, Raleigh seems to have more momentum. There’s the proximity to Dundon’s Hurricanes, who will soon begin a $1 billion project to transform 81 acres around the Lenovo Center into an entertainment district. (One could imagine squeezing a ballpark in there.) There’s more support for Raleigh’s MLB bid from local and state politicians; North Carolina Gov. Josh Stein spoke in support of the plan earlier this year.

Charlotte also lacks a group working publicly toward an eventual bid, while Raleigh has both Hurricanes leadership and a community-led campaign. That group, MLB Raleigh, existed before Dundon stated his intention to wade into MLB waters. The co-founders made merchandise and invited baseball fans to brewery meet-ups. They hoped to make enough noise that the media noticed, then local government, then a billionaire. Once that happened, things only got noisier.

“We’re just trying to prove that people want it here,” said MLB Raleigh co-founder Lou Pascucci, a designer at IBM. “This is a baseball town.”

WestAustin

General partnerStadium SitePublic funding for ballpark

TBA

TBA

TBA

The Austin Baseball Commission, a grassroots effort led by three 40-something entrepreneurs, is still in its nascent phase. The campaign went public last year and has checked off fewer boxes than the other potential expansion cities included here. That doesn’t concern the group’s CEO, Matt Mackowiak. Until MLB clarifies its expansion timeline, this is all prep work. In the end, Mackowiak said, what matters is the actual bid: the billionaire(s) bankrolling it, the incentives package and the real estate plan.

The greater Austin area represents an opportunity for MLB to break into a rapidly growing city that ranks as one of the largest domestic markets without a “Big Four” pro league franchise. San Antonio has the NBA’s Spurs, and Austin has a rabid college fandom at the University of Texas, as well as an MLS expansion team, Austin FC. There are two minor league teams in the region: the Double-A San Antonio Missions and the Triple-A Round Rock Express, just north of Austin.

“If you collapse Austin and San Antonio into one market like we will, much like the Spurs have done in reverse, we’re larger than the state of Utah,” Mackowiak said.

Beyond building a plan, a local supporter base and an executive team, the Austin Baseball Commission is scouting three potential stadium sites near the Austin airport, Mackowiak said. He believes MLB owners will want two new markets that won’t cause headaches — that fill seats, play in big-league ballparks, spend reasonably and won’t be long-term revenue-sharing recipients.

“As long as we have a lead investor, a serious (limited partner) group, an incentives package and a stadium plan, we think we have a really, really, really good chance,” Mackowiak said. “But we’ve got to put a bid together at the right time, then go out and make a case.”

Portland

General partnerStadium SitePublic funding for ballpark

TBA

Zidell Yards

Up to $800 million

After years of scouting potential stadium sites in and around Portland, the Portland Diamond Project now has a signed sale and purchase agreement for Zidell Yards, a 31-acre waterfront parcel near downtown Portland that looks out toward a cable-stayed pedestrian bridge over the Willamette River and the Cascade Range beyond.

The south side of the lot, which is bisected by the Ross Island Bridge, would have 16 acres of mixed-use development. PDP founder and president Craig Cheek said after poring over the property with consultants and architects, “We found no showstoppers. It’s a complex site, but sometimes the complexity only reinforces what an amazing site it’s going to be.”

Cheek believes a successful MLB expansion bid, including an expansion fee and ballpark construction, will be a $5-5.5 billion enterprise. He anticipates roughly half of the estimated $2 billion ballpark cost will come from public support. The Oregon legislature recently passed a bill that would provide up to $800 million in bonds for stadium construction, funded through income tax on player and staff salaries.

Cheek said his focus now is on “completing our capital stack” and determining a primary investor for the project.

“We are in active and advanced conversations with multiple parties that we know we need to anchor (a bid),” Cheek said. “I don’t have a definitive name or group I can give you, but I can tell you we’re making significant progress on that.”

When Portland first emerged as a serious expansion candidate, Las Vegas seemed to be the greatest threat to win the West Coast bid. Las Vegas went the relocation route instead, and now it’s Salt Lake City seemingly in the lead. Perhaps a stadium site and a general partner would help Portland gain a foothold in the eyes of the public. But being viewed as a frontrunner in 2025 is inconsequential compared to the contents of the bid these cities will eventually present to MLB and its 30 owners.

Salt Lake City

General partnerStadium SitePublic funding for ballpark

Miller Family

Power District

Up to $900 million

If there exists such a thing as a turnkey expansion option, it’s Salt Lake City. Big League Utah has broad bipartisan political support, a growing market, a massive stadium site, up to $900 million in public funding for ballpark construction and an ownership group with a reputation for stability and decades of experience owning pro sports teams.

Auto dealer Larry H. Miller bought the NBA’s Jazz in 1985, and his wife, Gail, assumed ownership upon his death in 2009. The Miller family sold the Jazz for $1.66 billion in 2020 and the car dealerships for a reported $3.2 billion in 2021; they own Triple-A Salt Lake, which recently moved into a new ballpark southwest of the city, and Real Salt Lake in MLS.

“Now you have the second generation of family who’s come along, and they stand on the shoulders of their parents,” Starks said. “They love sports. They love baseball in particular. So they said, we would love to be stewards of the next great American sport, which happens to be our pastime, and aligns with our family’s passion for community building.”

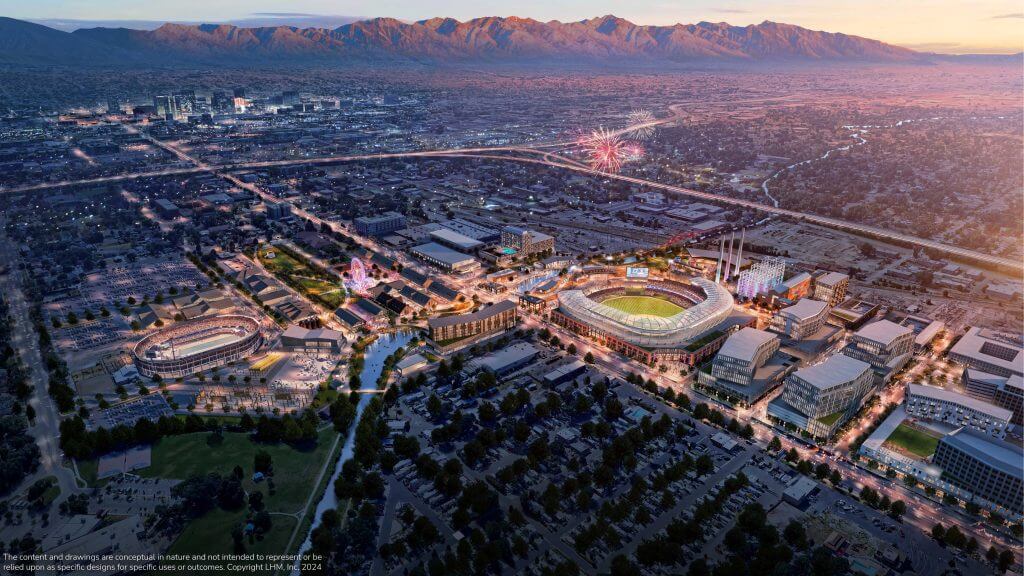

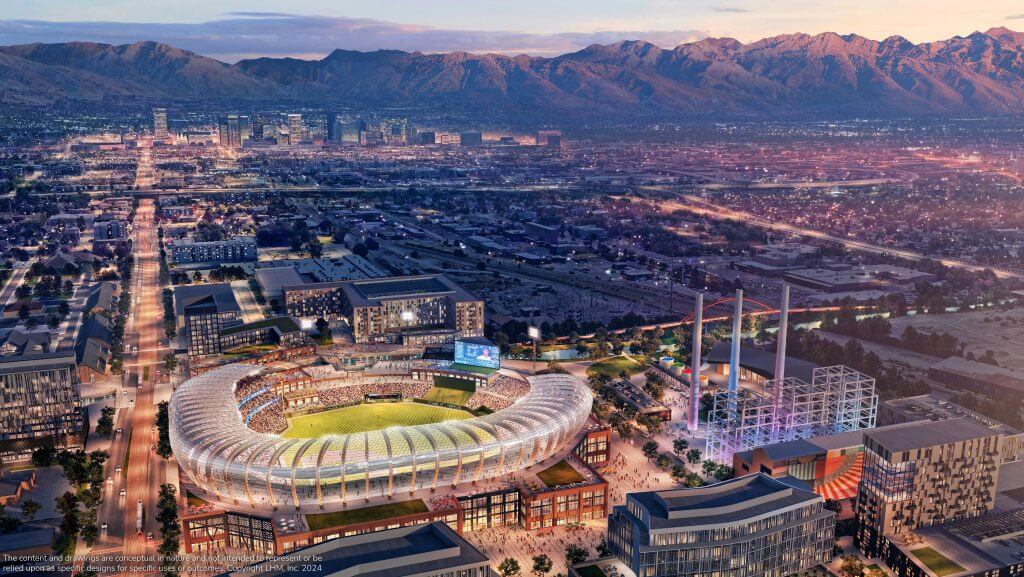

(Renderings courtesy of Big League Utah)

An MLB stadium is the proposed centerpiece of the 100-acre Power District site on Salt Lake City’s west side, a redevelopment plan toward which the Larry H. Miller Company has pledged more than $3.5 billion. The project will go forward whether or not MLB gives Utah an expansion team; crews will break ground on Rocky Mountain Power’s headquarters there later this year.

While Big League Utah is ahead of other potential expansion cities in completing priority tasks, there’s more to do than wait. Though the group released preliminary renderings of a stadium design, they’re still studying elements of the site and finalizing plans to be “truly shovel-ready,” Starks said, “to eliminate the risk for the commissioner and the other owners.”

“Even if you announce a project, it’s still incredibly complicated,” he said. “We’re taking all the steps necessary to de-risk it and be able to show, hey, we can (have) shovels in the ground and can submit plans within the first six months.”

(Photo: Brandon Bell / Getty Images)