Amanda Uhle had a recurring dream as a child.

She would open the windows and purge her house of excess: canned goods and stockpiled scrap fabric went out the window.

Jars of cinnamon were dumped on the kitchen floor. Dozens of shampoo bottles were emptied on the rug. This wasn’t about instilling order it was, she explains, about upending the disorder in which she existed.

‘It was a fantasy, a wish to escape from the oppressive forces we lived with,’ Uhle, 47, told the Daily Mail.

Her mother was an obsessive hoarder – a compulsion that drove the family into debt and Uhle to the brink of despair.

She describes the experience and impact of growing up in a household so squalid it was often too cluttered to find a place to sit down, in her new memoir, ‘Destroy This House.’

‘It made me uncomfortable, sad and anxious,’ Uhle said. ‘I counted the days until I could leave for college and be free of it all.’

In elementary school, Uhle thought it was perfectly normal for households to be messy.

Amanda Uhle’s mother was an obsessive hoarder, a compulsion that drove the family into debt and Uhle to the brink of despair

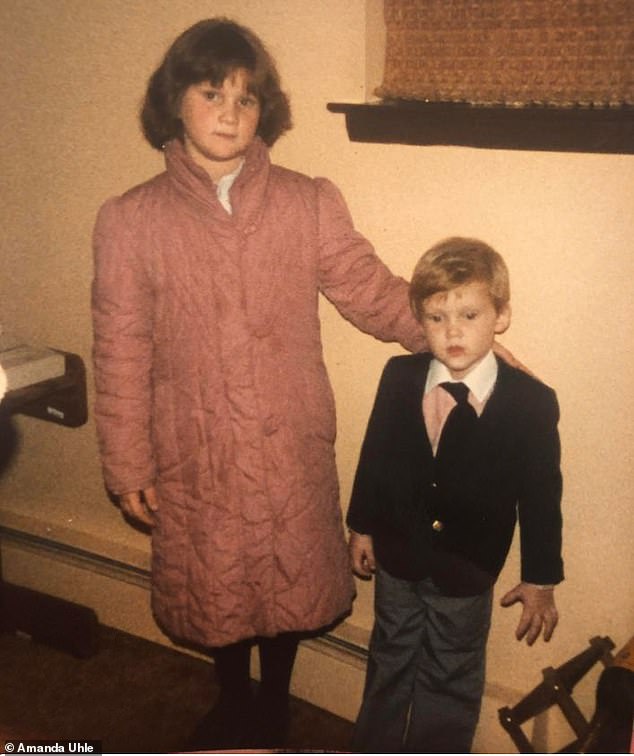

In elementary school, Uhle (pictured alongside her brother, Adam, in 1985) thought it was perfectly normal for households to be messy

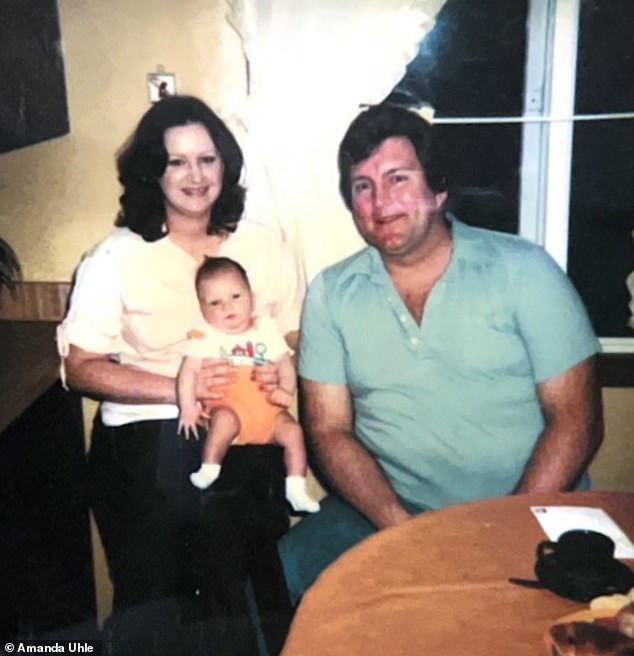

Uhle’s mother, Sandra (pictured above with her late husband Stephen), was an obsessive hoarder – a compulsion that drove the family into debt and Uhle to the brink of despair

‘It just seemed like something parents did,’ she said.

But as she got older, she realized her home was uniquely untidy.

Her mother, Sandra Long, was half-committed to a host of fly-by-night jobs. She dabbled in realty, selling rubber stamps and assisting in dress shops before eventually becoming a hospice nurse.

She would buy yards of fabric, intending to make clothes that she never did. The material, however, took over the dining table, while dirty dishes and scattered food packages covered the kitchen counters.

One time, Uhle recalled, her father Stephen was forced to butter a piece of toast in the palm of his hand because every surface was taken.

Food rotted everywhere in the home.

The overflowing refrigerator was stuffed with so much uneaten food that it wouldn’t shut. Most of it would spoil, and Uhle lost count of how many times she found sludgy cucumbers, moldy cheese or curdled milk on its shelves.

Inside, there was no room for leftovers, so half-eaten meals often simply lay out on the counter, deteriorating and attracting flies.

Compounding the problem, her mother rarely took stock of the kitchen cabinets and would return from the grocery store with canned goods, boxed dinners and perishables that weren’t needed and would inevitably be left to decay.

Occasionally, Uhle would attempt to make in-roads into cleaning things up. But her efforts would only provoke her mother, who would go into an ‘uncontrolled fury.’

Uhle remembers reaching into a cupboard – ‘stacked full of at least five times as much food that would fit’ – to fish out a snack and plucking a granola bar from the oldest-looking box.

‘It would bother me as a 10-year-old that my mom would buy another box of granola bars when we already had 30 others at home,’ she said.

‘So, I reached for one of the older boxes because I had this feeling I should use up some of the old stuff first.’

She unwrapped the granola bar, took a bite, then looked at it and saw that it was moving.

‘It was full of wriggling maggots,’ she said.

Uhle complained to her unsympathetic mother, who only shrugged her shoulders and told her to ‘just spit it out.’

One time, Uhle recalled, her father Stephen was forced to butter a piece of toast in the palm of his hand because every surface was taken

According to Uhle, ‘It would bother me as a 10-year-old that my mom would buy another box of granola bars when we already had 30 others at home.’

Sandra had tried to feed her family rancid food on more than one occasion – yogurt four years expired, hot dog buns with the mold torn off, meat that had turned gray. Decades later, Uhle’s stomach churns at the memories.

Shopping for clothes with her mother was equally nightmarish.

If Uhle so much as looked at an item or felt the material during a trip to a store, Sandra would place it in the cart and insist on buying it, no matter how much Uhle protested.

The cover of Uhle’s memoir, in which she recalls her chaotic childhood

She longed to be like a regular mother and daughter who enjoyed the thrill of weighing up choices, trying on outfits and selecting one or two pieces to bring home.

But Sandra and Stephen were feckless, they preferred a ‘hands-off method of managing their money,’ Uhle writes – and it showed.

Dusty bills and receipts stacked up on the top of the hot tub in the backyard that was never used as anything other than a repository for discarded paperwork.

After a while, anything that looked like a bill would be thrown in the trash. As a child, Uhle routinely answered the phone, ignored by her parents, only to be barked at by debt collectors.

‘You’d find a stack of white envelopes under the remnant of someone’s sloppy Joe sandwich or cracked eggshells or a plastic cheese wrapper,’ Uhle writes.

As her father jumped from job to job, the family moved state to state.

Uhle describes Stephen as a wheeler dealer type, who worked as a cleaning products salesman before hawking books door-to-door, selling real estate, then entering a Lutheran seminary as a pastor.

As a result, the family was in constant upheaval, relocating no fewer than six times between states as far afield as New York, Indiana and Michigan.

When the family moved to a neighborhood in Detroit during her teenage years and Uhle made friends at a new high school, she was too embarrassed by the mounting junk to invite them around.

If someone was picking her up, she’d wait outside on the street rather than risk them knocking on the door.

Uhle describes her father, Stephen,(pictured with her mother and Uhle as a baby) as a wheeler dealer type, who worked as a cleaning products salesman before hawking books door-to-door, selling real estate, then entering a Lutheran seminary as a pastor

Uhle pictured outside the family’s Long Island home. The family was in constant upheaval, relocating no fewer than 10 times between states as far afield as New York, Indiana and Michigan

Uhle as a teen in 1995 at a friend’s house; if someone was picking her up, she’d wait outside on the street rather than risk them knocking on the door

‘I’d make an excuse, saying, ‘It’s not a good time’ or ‘Your house is better, and I like it more,’ Uhle said.

Uhle was 18 years old when, in 1996, she finally broke free, moving hundreds of miles away to attend college in Chicago.

At last, she had a room where piles of belongings did not take up one side of the bed and the countertops were clear of clutter. Her recurring dream to obliterate her childhood home stopped the very first night she arrived.

‘It was beautiful,’ she said.But, while Uhle escaped, her mother never stopped hoarding – even after her father died from cancer in 2013 and she had been moved into an assisted living facility.

She would call Uhle, by then a mother herself, saying she couldn’t close the freezer because of the amount of food inside.

Neighbors complained about the smell of rotting produce emanating from the apartment and the management threatened eviction.

Sandra died of kidney failure in 2015 at the age of 64. For Uhle, there was no relief in her passing. Instead she felt a wave of sadness that she had never truly bonded with her mother, and never come to understand the compulsion that overwhelmed her mother’s life and, with it, her own childhood.

‘I’ve concluded, through writing my book, that even those who are supposed to be closest to us and who we love deeply, can be mysteries,’ she said.

Following her death, the contents of Uhle’s mother’s apartment were removed by a junk company. It took several days to empty the place.

Once it was done Uhle surveyed the space and saw, in its emptiness, the fulfilment of the fantasy she had harbored as a child – that dream of purging the property for good.

‘Destroy This House’ by Amanda Uhle will be published by Summit Books on August 23, 2025.