It was a perfect snapshot, capturing a moment in time. As the Old Trafford crowd roared, Alejandro Garnacho wheeled away in celebration and propped himself on an advertising hoarding, hands on hips, sitting there with a beaming smile as Kobbie Mainoo and Rasmus Hojlund joined him.

Garnacho’s goal put his team 2-0 up against West Ham United, but, for Manchester United and their supporters, it signified something far more than a welcome Premier League victory. It was their third win in a week and, in a difficult 2023-24 season, it felt as if they had settled on a way forward at last, building around the youthful promise of Garnacho, 19, Mainoo, 18, and — less assuredly, perhaps — Hojlund, 21.

The image went viral. The club’s official website called it “iconic” and, a few months later, “prophetic” after Garnacho and Mainoo scored in the FA Cup final victory over Manchester City. The trio needed little encouragement to recreate the pose when the new home kit was launched that summer. “Hopefully it can go on to be an iconic picture and hopefully we can do great things for the club,” Mainoo told club media.

Iconic? Hmmm. Ironic, possibly, but symbolic is probably the best word to describe the photograph taken in February 2024 — and not in a good way. Eighteen months on, it symbolises not the bright future the three of them were dreaming of, but a club where promise and optimism wither so quickly these days, where yesterday’s bright young hope is, once again, cast as today’s problem child.

Last night, United agreed to sell Garnacho to Chelsea for a £40million ($54.1m) transfer fee and, from within Old Trafford, it was presented as a great solution to a summer-long problem. It is the fourth-largest player sale in the club’s history and a huge profit on a player signed for a six-figure compensation fee when he arrived from Atletico Madrid as a 16-year-old. It represented a decent step up from Chelsea’s opening offer of £25m — and all of this for a player who had been agitating for a transfer and whom coach Ruben Amorim was relieved to see the back of.

Hang on a minute. Last summer, Garnacho, along with Hojlund and Mainoo, was among a small core of players who were considered integral to United’s future plans — “ringfenced” in the words of one official — at a time when just about everyone else in the squad had their price. Hojlund’s anticipated departure to Napoli on an initial season-long loan is less surprising, but The Athletic’s revelation last night that Mainoo had asked the club to be allowed to leave on loan in search of first-team football is, like Garnacho’s fall from favour, a sign that something has gone terribly wrong.

On November 6 last year, five days before Amorim took charge, the CIES Football Observatory, based in Switzerland, released its list of the most valuable players in world football under the age of 21.

CIES would not claim its algorithm to be foolproof, but the fact that Barcelona prodigy Lamine Yamal was top of that list with an estimated transfer value of €180.9million (£156.2m or $211m at today’s exchange rates), barely three months after his 18th birthday, suggests some degree of reliability.

What is striking about that list is that Garnacho was second, valued at €114.8m and — after a group that included players from Paris Saint-Germain (Warren Zaire-Emery and Joao Neves), Manchester City (Savinho and Rico Lewis) and Real Madrid (Endrick and Arda Guler) — Mainoo was ninth, valued at €74.8m. And if you had proposed to anyone at United back then that they would be selling Garnacho to Chelsea for £40m and open to similar offers for Mainoo, they would have laughed.

The financial position is a factor, particularly in the context of the Premier League’s profit and sustainability rules (PSR), which have had the unwanted effect of encouraging clubs to cash in on homegrown players at the first opportunity.

But let us not overstate the PSR factor. If Amorim had regarded Garnacho or Mainoo as important players for United’s future, they would have been off-limits and there would be a determination — almost certainly shared by the players — to extend and improve upon the contracts they signed in early 2023. Instead, he quickly concluded that Garnacho, in terms of technical profile and attitude, did not fit his plans.

Amorim’s position on Mainoo has been less clear-cut, but for the player to be seeking a loan deal, having been so frustrated at being kept on the bench for United’s first two Premier League matches, is alarming, whether the club sanctions such a move or — as it appears for now — not.

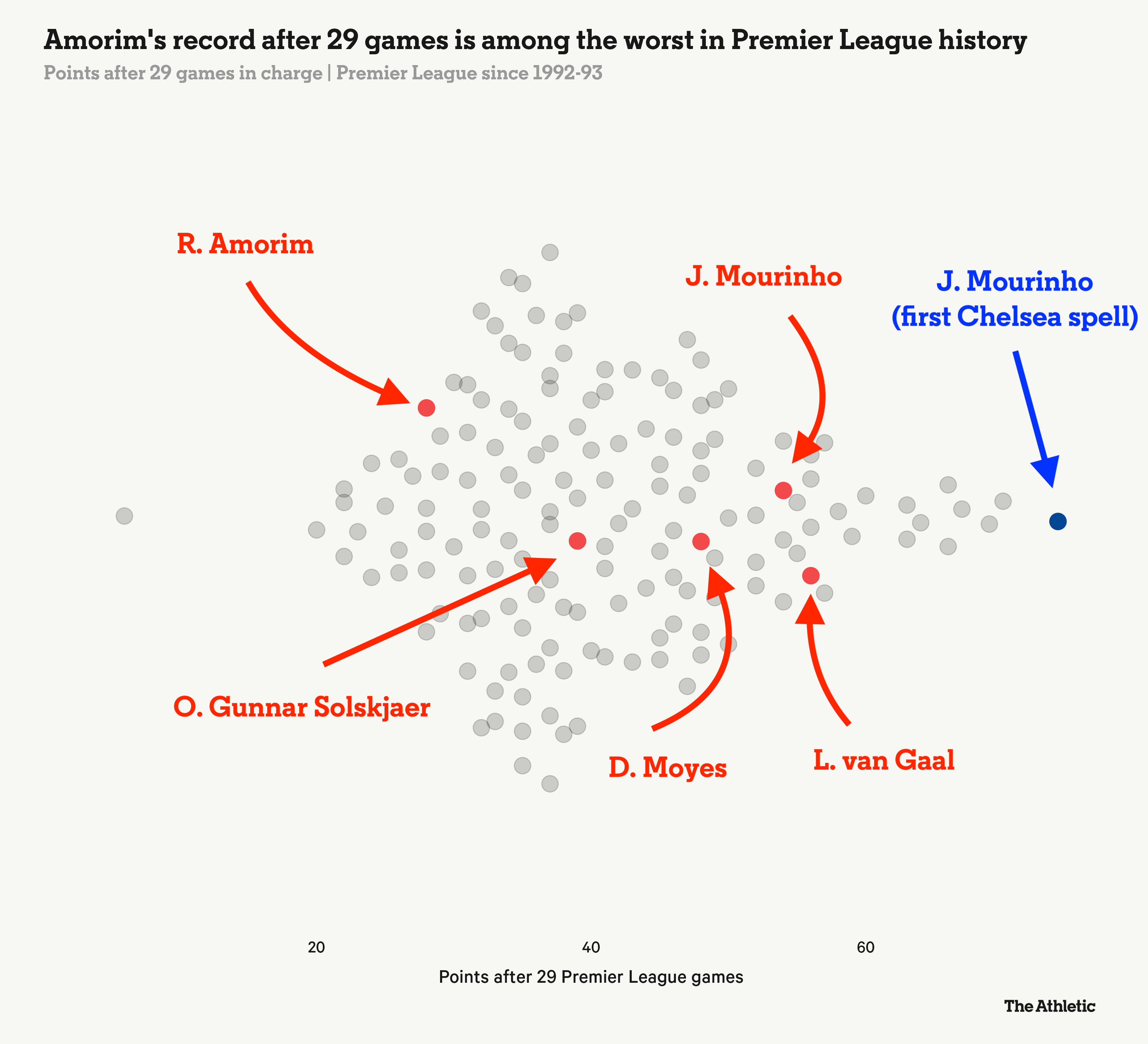

Are United’s supporters OK with this? Since Amorim took charge last November, they have won seven Premier League games out of 29, scoring 33 goals. For all the belief in Amorim, for all the mitigating circumstances around his appointment, the results have been terrible and performances have not been much better.

This isn’t just bad by United’s lofty standards. In the Premier League era, dating back to 1992, there have been just 13 cases of a manager picking up fewer than 28 points from his first 29 games. Among these 13 are some of the most infamous managerial tenures in the competition’s history: Steve Kean at Blackburn Rovers (26 points), Alan Ball at Manchester City (26 points), Mark Hughes and Harry Redknapp at a chaotic Queens Park Rangers (24 points), Mike Walker at Everton (23 points), John Gorman at Swindon Town (22 points), and David Moyes at Sunderland (20 points).

As an aside, bottom of that list by far is Mick McCarthy’s spell at Sunderland, but his miserable total of six points from his first 29 Premier League games began in March 2003 with a team doomed to relegation and was punctuated by two seasons in the Championship. Still, for those who imagine things can’t get any worse for a beleaguered manager, there is a popular McCarthy-based meme to warn you otherwise.

Manchester United: 2013-present pic.twitter.com/fsTLgYPtC0

— James Benge (@jamesbenge) August 27, 2025

We digress. It is one thing to believe a manager must be given time to implement his vision and his strategy, but… what if a vision built around a three-man central defence and a central midfield axis of Bruno Fernandes and Casemiro, in 2025, is fundamentally flawed? What if, sooner or later, we find ourselves looking back at Amorim’s tenure and reflecting that this undeniably talented coach never stood a chance of turning the tanker around? And what if, by backing the immediate preferences of a beleaguered coach over the long-term potential of Garnacho and Mainoo, the hierarchy is continuing a long-term trend by making a short-sighted, regrettable decision?

Such questions will raise the hackles of many United supporters, for whom faith in a manager’s judgement is fundamental to their belief system. This is a fanbase that, recalling how Sir Alex Ferguson turned things around from the dark of the early 1990s, doesn’t give up on managers lightly.

There has been a succession of them since Ferguson retired in 2013 — David Moyes, Louis van Gaal, Jose Mourinho, Ole Gunnar Solskjaer, Ralf Rangnick, Erik ten Hag, Amorim — and all of them, while exasperated by aspects of the job, have found themselves moved by the extent to which the supporters have kept backing them. As Andy Mitten articulated yesterday, worries and weariness on the terraces do not equate to an appetite for another change.

A culturally ingrained belief in the manager’s authority is strengthened when stories emerge of young players sulking over a lack of opportunities when their performances have not been up to scratch. In the cases of Mainoo and Garnacho, such feelings are heightened further when you hear of agents outlining the kind of wage expectations that suggest a detachment from reality.

Some of us were far less giddy than, say, Rio Ferdinand or United’s social media team when Garnacho and Mainoo initially broke into the first team. Mainoo showed considerable potential in early 2024, impressing with his composure, guile and technical ability, but as a part of a dysfunctional midfield that proved largely incapable of controlling matches under Ten Hag. Garnacho’s undeniable promise was of a type that was raw and wildly inconsistent, not just from one week to the next, but at times from one minute to the next.

But they were teenagers, playing with a verve and a flair that felt in keeping with the club’s traditions. There have been few United players over the past decade for whom that could be said. And when young players are being hyped not just by supporters or by the media but by their club’s hierarchy, putting them at the forefront of marketing campaigns, telling them they represent the future of one of the biggest clubs in football, then perhaps they can be forgiven for getting ahead of themselves.

What is it about the modern Manchester United that sucks the joy, fun and positive energy out of everyone and everything? Luke Shaw, their longest-serving first-team player, told reporters on this summer’s pre-season tour of the United States that “it can be quite toxic, the environment, it’s not healthy at all”. Many a team-mate, past and present, would share that view.

As has been written here with almost wearying regularity, it is a club that has lost its way under the Glazer family’s wretched ownership. The malaise runs so deep, from boardroom to dressing room.

It isn’t just players who are afflicted. It is managers, too. Amorim arrived at Old Trafford last November radiating energy and charisma, but there are times when he looks and sounds utterly beaten, drained of enthusiasm, openly questioning his ability to turn the tide of negativity.

(George Wood/Getty Images)

He looked forlorn on the touchline during the Carabao Cup humiliation in the wind and rain at Grimsby Town on Wednesday night: shuffling the magnets on his tactics board in search of an epiphany, then unable to watch the penalty shootout as his team fell to a humiliating defeat against fourth-tier opposition. In his post-match interviews, he was scathing of a group of players whose performance “spoke really loud today what they want”.

And for all Sir Jim Ratcliffe’s condemnation of the “mediocre” culture he found after joining the board in 2024, for all the much-trumpeted executive appointments and talk of restoring a “high-performance environment” at a revamped training ground, for all the efforts to identify troublemakers and move them on, for all the undoubted faith in Amorim and for all the excitement that greeted rare flashes of creative enterprise in an unfortunate defeat by Arsenal, the whole situation is starting to look bleak and horribly familiar.

Time and again in recent years, under a succession of managers, there has been a rush behind the scenes to blame that “toxic” culture on individuals, which in itself is pretty toxic, isn’t it? One perceived troublemaker after another has been shipped out and, to judge by Amorim’s post-match comments at Grimsby, three games into the latest “cultural reset”, the same negative environment persists.

And this is August 2025. You can’t blame Paul Pogba and Jesse Lingard anymore. You can’t even blame Marcus Rashford.

For Rashford, the transition from wholesome homegrown wonder boy to pariah was gradual, even if the speed of the final unravelling — from a huge new contract in the summer of 2023 to loan moves to Aston Villa in January and Barcelona this summer — might have felt rapid. For Garnacho and Mainoo, the downgrading from indispensable to disposable seems to have happened in the blink of an eye.

There are those at Carrington who will be happy to see the back of Garnacho. Some of them will be indifferent if Mainoo follows the same path, whether in the next few days or in the January transfer window, even if others hope he will knuckle down on the training ground and force a re-evaluation from Amorim. Hojlund, if he departs, might be missed for his good nature, but not for his on-pitch contribution, which has been that of a young player struggling in a team where there is such a glaring disparity between the pressure to deliver and the opportunity to do so.

Still, for a few weeks in early 2024, when Garnacho was flying and Hojlund scored eight goals in as many matches, it felt so promising. That was the same period when Mainoo broke into the team and looked as if he was born to play in United’s midfield, chipping in with a goal against Newport County in the FA Cup, a last-gasp winner at Wolverhampton Wanderers, a peach of a strike in the 2-2 draw against Liverpool, and then, best of all, a goal and a man-of-the-match performance against Manchester City in the final.

So yes, when Garnacho scored that goal against West Ham and basked in the glory, it felt like a moment in time. But that is all it has proved to be — a fleeting moment of excitement and possibility — because increasingly it feels that nothing good can thrive for long at a club where so many conflicting ideas and agendas persist and where, in the absence of a clear vision and leadership, the culture that prevails in the boardroom and dressing room is so unhealthy.

That is what Amorim has found himself up against and, in that climate, it is only to be expected that managers, too, find themselves on the back foot, abandoning long-term thinking at the altar of self-preservation.

Only time will tell whether he and the United hierarchy have truly found a way towards a better, brighter future. But more than anything, that snapshot of Garnacho, Mainoo and Hojlund serves as a reminder of how quickly faith evaporates at the modern-day Manchester United — and if that applies to young players, it can certainly apply to coaches too.

(Top photo: Paul Ellis/AFP via Getty Images)