The remarkable seasonal flow of thousands of bison into and out of Yellowstone National Park is both a relic of an earlier, pre-settlement era and a source of great debate — Montana’s even sued in pursuit of fewer bison.

But there’s now less debate about the ecological good the herds of native herbivores bring to the landscape. A new study published in the journal Science shows that the migratory herds of bison effectively function as nature’s fertilizers, providing an astonishing 2.5-fold bump in crude proteins growing into the grasslands that blanket Yellowstone’s Northern Range.

“It’s mainly coming from urine and feces,” said Jerod Merkle, a professor of migration ecology and conservation at the University of Wyoming. “What happens is it goes into the ground, and it lights up the microbial ecosystem in the soil.

“It’s a circle,” he added. “Bison graze, pee and poop. That facilitates the insects and the microbes, which then creates better soil, which then the plants take up again.”

Bison and other critters, in turn, benefit.

A grazing lawn site in the Lamar Valley shows heterogeneity in grazing patterns during summer. (Bill Hamilton)

A grazing lawn site in the Lamar Valley shows heterogeneity in grazing patterns during summer. (Bill Hamilton)

Merkle, along with co-authors Chris Geremia of Yellowstone National Park and Bill Hamilton of Washington and Lee University, even estimated the net benefit migratory bison add to the landscape in terms of crude protein. There’s not actually more grasses growing — even though they’re heavily grazed, the volume sprouting off the landscape stays about the same.

“It’s not biomass,” Hamilton told WyoFile. “It’s more productive — the nutritional quality is improved. There’s more nitrogen and crude protein in the forage.”

Across Yellowstone’s Northern Range, researchers calculated that the bison stimulation effect added 3,549 tons of crude protein to a 329-square-mile region, which pencils out to an estimated 37-pounds-per-acre bump in nutrition.

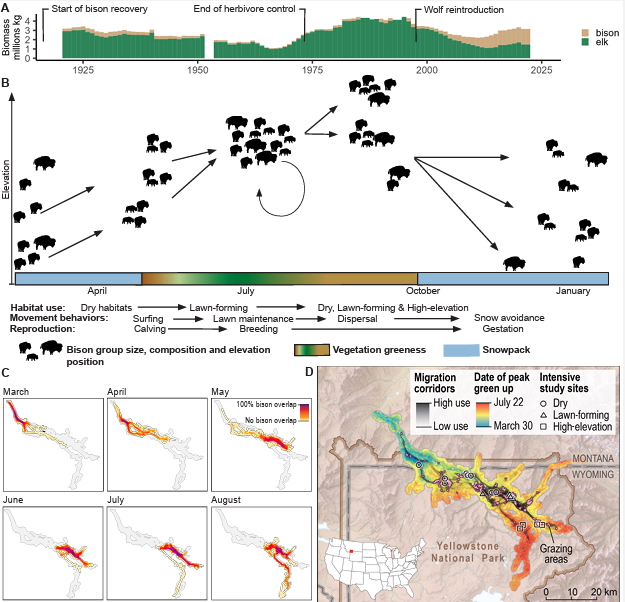

Figure from study. A) Bison now account for the majority of herbivore biomass on Yellowstone’s northern range, which has a complete guild of migratory herbivores and their carnivores. B) Beginning in spring at lower elevations in the West, bison move in dispersed groups, calving on the move and following the “green wave” of emerging vegetation. C) As they ascend, they gather in larger, coordinated groups on floodplains and wet grasslands, forming grazing lawns crucial for nurturing calves D) The main migratory route in Yellowstone covers about 100 kilometers from west to east in the northern part of Yellowstone. (University of Wyoming)

Figure from study. A) Bison now account for the majority of herbivore biomass on Yellowstone’s northern range, which has a complete guild of migratory herbivores and their carnivores. B) Beginning in spring at lower elevations in the West, bison move in dispersed groups, calving on the move and following the “green wave” of emerging vegetation. C) As they ascend, they gather in larger, coordinated groups on floodplains and wet grasslands, forming grazing lawns crucial for nurturing calves D) The main migratory route in Yellowstone covers about 100 kilometers from west to east in the northern part of Yellowstone. (University of Wyoming)

The benefits aren’t uniform. There’s a “mosaic” of bison grazing’s influence on the landscape, Merkle said, both in terms of space and time due to seasonal migrations. Grazing provided 156% more crude protein in the lawn-like habitats like the Lamar River valley and 155% more in high-elevation landscapes. In dry areas, the effect was slightly more subdued, with a 119% increase.

To make those calculations, the research team assessed grazing and nutrient dynamics at 16 sites from 2015 to 2022. They used fenced exclosures moved every five weeks and kept track of datapoints including plant consumption, plant growth and plant composition, nutrient cycling, plant and soil chemistry and soil microbial populations.

Merkle, Hamilton and Geremia did not detect overgrazing, which can result in declining plant productivity and diversity and soils becoming compacted. Rather, they detected the opposite and a lot of variation across the landscape, Merkle said.

“There are spots that bison hit hard, and places they don’t touch at all — and that can change over the years,” he said. “The cool thing is that allowing these bison to freely move across the landscape at a big scale, creates the heterogeneity.”

A fixed exclosure at one of the grazing lawn sites in mid-summer. Fixed exclosures are installed in spring and stay up until October to quantify the amount of biomass produced in the absence of grazing. (Chris Geremia/National Park Service)

A fixed exclosure at one of the grazing lawn sites in mid-summer. Fixed exclosures are installed in spring and stay up until October to quantify the amount of biomass produced in the absence of grazing. (Chris Geremia/National Park Service)

On the broader western landscape, it’s an effect that’s largely been lost. Although there are a few exceptions and efforts to grow more free-roaming herds, bison are generally not allowed to behave like wildlife in the modern world.

In Wyoming, for example, bison are classified as a big-game species where the roughly 500-animal Jackson Herd roams and in the unoccupied Absaroka herd unit east of Yellowstone. But elsewhere, they’re not considered wildlife and instead considered “privately owned or bison running at large.”

That’s not particularly unique. Today, about 95% of the 400,000 bison that exist are privately owned or commercially raised for their meat. The few “conservation herds” that exist average just 300 animals, and they’re “almost universally managed in constrained areas with strict limits on numbers and movements,” according to the Science paper. It’s a far cry from the 20,000-strong bison herd that early explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark encountered in South Dakota in 1806, which was just a sliver of the tens of millions that existed before white settlers hunted the American bison to near extinction.

Yellowstone is one of the very few exceptions. The herd-oriented, migratory plant-eating megafauna — and their quantifiable ecological effects — have been lost almost everywhere else.

“The closest relatable ecosystem is the Serengeti, where we have big herds of wildebeest and zebra moving and migrating in a similar way and creating a similar nitrogen and ecosystem cycle,” Merkle said. “It’s kind of cool for Yellowstone to be on par with a Serengeti-type place.”