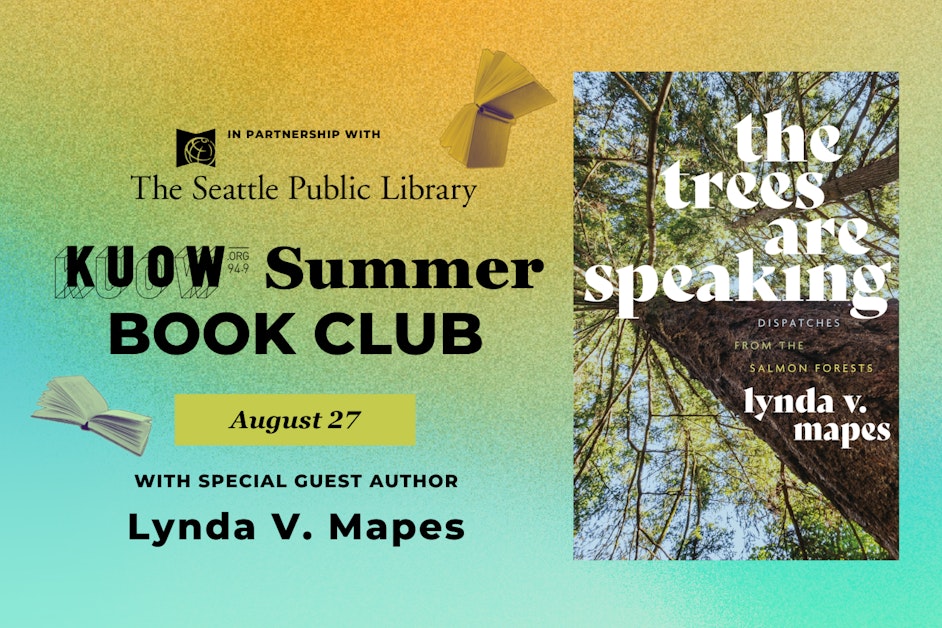

This month, the KUOW Book Club read Lynda V. Mapes’ new book, “The Trees are Speaking: Dispatches from the Salmon Forests.” Mapes joined KUOW’s Katie Campbell for a live conversation at the Seattle Central Library, the final in a three-part summer series in partnership with Seattle Public Library. The full audio from the event is available below.

W

hen I was writing the questions I wanted to ask Mapes about “The Trees are Speaking,” what I wanted to know most was what it was like to walk among trees, hundreds of years old, with her.

She writes with such reverence for these great beings, and while they inspire awe in me, too, I wanted to experience them through her. It’s rather challenging to gather several dozen people together for a book talk out into the woods, though, so I settled for asking her to describe what she sees, smells, hears as she walks through an old-growth forest.

RELATED: Subscribe to the KUOW Book Club newsletter here

“The very first thing is the tread underfoot, that very, very soft tread, the deep, deep forest floor that’s been building for thousands of years,” she told a live audience when we spoke at the Seattle Central Library Wednesday night. “The next thing, of course, is the quiet. It’s like a recording studio, because it is so soft, every surface is soft and rounded. The sound is only surpassed by the smell. It’s that fructifying funk. It’s that gorgeousness of soil and moss and wet. And then, the quality of the light. It’s ever-changing.”

And it’s not any one thing, these forests.

“It’s not just big trees, and they’re not damp and dark places,” she said. “These are places that are defined by variety. Yes, there are enormous trees, but there are also big gaps where a tree has fallen over and sunlight is pouring down to the forest floor, and the next generation is rising. There’s an understory replete with everything from ferns to berries to even tiny, tiny little Calypso orchids, the flowers no bigger than your pinky nail. To me, it’s the variety of the trees, their species, but also the textures and the age classes in a true, natural old-growth forest.”

Mapes speaks of these forests in the same way she writes about them: with the utmost respect, joy, and immediacy.

Much of our conversation, like her book, dwelled on the systematic destruction that has been done to these now rare forests and the terrible impact their deterioration has on surrounding ecosystems.

As much as I would have liked to linger on Mapes’ prose, I quoted some of the passages in “The Trees are Speaking” that left me furious with humanity. Passages like this one about the abandoned Lincoln Paper and Tissue mill in Maine:

The mill produced products of everyday life: the postcards that tumble out of magazines, trying to get you to subscribe. Paper towels, napkins, plates, and stationery. It specialized in deep-dyed tissues used for pleasantries: party streamers, paper napkins, and tablecloth sets. In producing these ordinary things, the mill discharged extraordinary pollution in the Penobscot River: dioxin and furan, contaminating the fish, sediments, and other natural resources. … Dioxin is a potent and persistent pollutant that causes cancer in multiple species, including humans, disrupts the endocrine system, and suppresses the immune system.

THE TREES ARE SPEAKING, PAGES 123-124

But at least we had pretty party streamers for so-and-so’s birthday, eh?

“These are terrible poisons that are created by making very ordinary things,” Mapes said. “I’ve bought party streamers. I’ve bought those tablecloths. … Look, I live in a wood house. I love to write with pencil on paper. I worked at a newspaper for 40 years, different papers, and I write books. So, I’m a big wood-products user. But one of the things I wanted to talk about in this book was beginning a movement for local woods, similar to local food, and respect for wood-product producers, such as we have for farmers.”

She makes that argument in the book, too.

What if we insisted our local public buildings were made from local wood that was actually sustainably sourced, not just clear-cut? What if we took pride in not the big beams from century-old trees in grand and even second homes but thrifty, small homes made with wood recycled from teardowns and built with innovative products made from lower-value wood, such as wood fiber insulation? Can’t we create tiny house envy, instead of lust for bigger, and even second homes? Can’t we get more excited about a really big tree left in the forest for wildlife than we do about yet another, even bigger house for us? Whatever happened to the less-is-more movement of the 1970s? It has become virtually unallowed speech, in a consumption-oriented society that lusts for stuff, yet is disconnected from our own personal consumption. That we would even think about the wood products we use at all, or the people who make them, and the forests they come from, would be a good start.

THE TREES ARE SPEAKING, PAGE 214

What Mapes is proposing would be a major cultural shift, and she knows that. Not just because she’s asking for a reversal of our consumerist behaviors, but also because it would mean spending more money on products like toilet paper and wood beams — money not everyone has to spare.

RELATED: ‘Old trees matter.’ Seattle author Lynda Mapes is writing to save them in her new book

I asked her how that can be accomplished when some folks in Seattle struggle to afford housing and food.

“One of the first things I would like to see, Katie, is a more equitable society,” she said. “This only works if communities are healthy. To the extent they’re living in exploitive systems and oppressed, they’re not going to be worried about the price of plywood. They’re going to be worried about feeding their kids. Health starts at home, and health has to be throughout society. If you’re living in the kinds of inequitable society that we are today, people have much more serious things to worry about in their lives, and that’s not how it should be.”

In her book, Mapes’ shows the way several tribes across the continent have traditionally raised their communities, taking from the land but with generations of prosperity and environmental responsibility in mind.

She saw it for herself on Penobscot Indian Territory in Maine, not far from the abandoned Lincoln Paper and Tissue mill.

Although they are cut, Penobscot forestlands are managed for multiple values: consistent income, jobs for tribal members who get hiring preference, water-quality protection, and enhancement and protection of the cultural integrity of the tribe. Clear-cuts, where they do them, usually are limited to less than five acres… a little bigger, maybe eight acres, if they are done primarily to create open areas for wildlife such as deer. The tribe does not use herbicides on their land, and all regeneration is natural. … They weren’t just managing these lands for clients or unknown investors. This was their home place, forever.

THE TREES ARE SPEAKING, PAGES 156-157

“I really think this is a fundamental question of values,” Mapes said. “It’s a much bigger question than how do we log or where do we log. By the end of the research on this book, I felt like logging was like quaint, at least, it’s a choice. It’s something under our control. I mean by the combined forces of globalization and climate and our forest practices of the past, we’ve created a situation in which, even in protected areas, our forests are under attack by bugs, by disease, by hot drought, by fire. … It’s about how we decide we’re going to live on this land together, and as long it’s about commodification of everything, even one another — that’s what’s brought us to where we are today.”

There may not be an exact prescription to set all of that right, but Mapes did offer some guidance to save our old trees, guidance to ponder as we wrap up this summer reading series:

Stop breaking things. Start fixing things. Stay together. Keep the big picture and the long game in focus. Share the cost and the work. And keep on going.

THE TREES ARE SPEAKING, PAGE 215

Listen to our full conversation by hitting the play button at the top of this post.

—————————————————————————————-

Spoiler alert: For those of you who like to plan ahead, we’ll be reading Seattle author Daniel Tam-Claiborne’s debut novel, “Transplants,” in September. And Daniel is set to join me for an interview to conclude our reading.

“Transplants” follows two young women — one Chinese and one Chinese American — on a university campus in rural Qixian, where they’re both met with hostility. Together, they learn what it means to be their truest selves in a world that doesn’t know where either of them belongs. It’s an exploration of race, love, power, and freedom.

Look out for the reading schedule on Sept. 1.