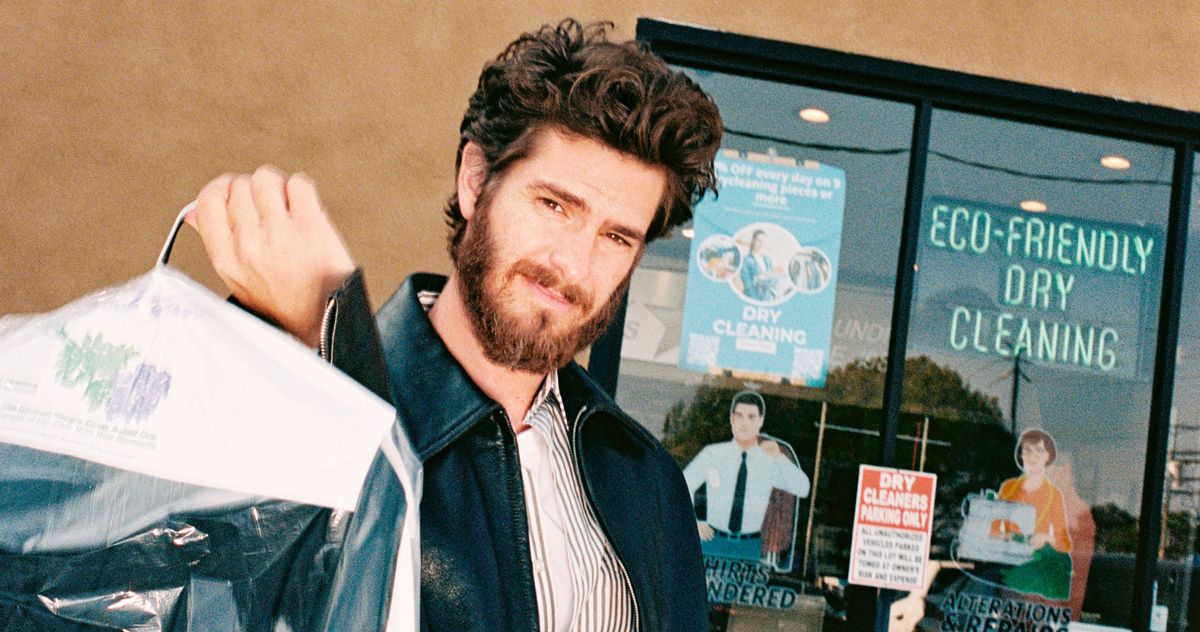

PRADA Shirt, at prada.com.

Photo: Anton Gottlob

The first scene Andrew Garfield shot for his new movie, After the Hunt, is an explosive encounter in which his character, a Yale philosophy professor named Hank Gibson, angrily confronts a student — who has accused him of sexual assault — in front of her teacher and classmates. Directed by Luca Guadagnino, whose films are known as much for their emotional extravagance as their impish button-pushing, After the Hunt is a Me Too psychodrama that dares to grab a few third rails, and the scene features a lot of yelling and door-slamming and students tearfully cowering. Garfield was feeling the weight of taking on such a fraught character. “I was very serious, just pacing around the corridors of that set,” Garfield says. “And Luca’s like, ‘Darling, are you going to be like this all the time?’”

The role, which sees Hank touching women creepily and flaunting his disdain for political correctness, cuts against Garfield’s good-guy reputation. In person, his pleasantness comes through in gently insistent waves. He is soft-spoken and attentive and unflaggingly polite. He puts great thought into his responses to your questions, and when he’s finished, he’ll smile a little smile to indicate I’m done talking now. May I have another? Even when he is dressed in Hollywood incognito — tinted glasses under a dark cap — his brown eyes somehow still absorb you in their benevolent depths. He says heartfelt things like, “I want to know people. I want to be intimate with people, and I want people to be intimate with me.”

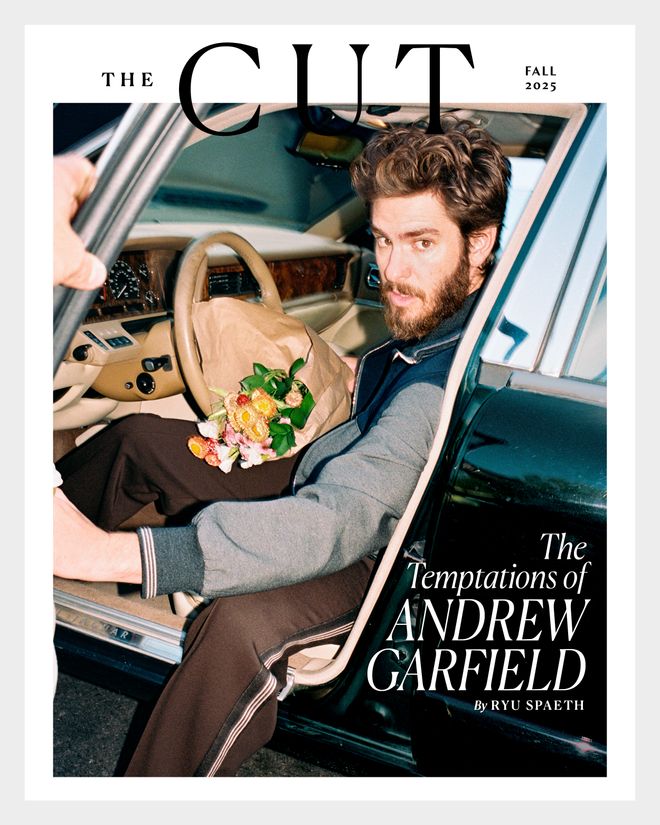

The Cut Fall Fashion 2025

He usually plays nice guys, too. As Eduardo Saverin in The Social Network, Garfield is a naïf who gets cheated out of hundreds of millions of dollars because he makes the terrible mistake of trusting his best friend. As Spider-Man, he is a boy wonder whose real superpower is how much he cares about other people. In Martin Scorsese’s Silence, he is a Christian martyr with a seemingly limitless capacity for being persecuted. And in We Live in Time, he plays a father who is so supportive of his dying partner, so steadfast, so nice, that even Garfield has a few problems with him. “Well, he’s a bit of a pushover,” Garfield admits. “Where’s the guy’s spine?”

We’re speaking at a coffee shop on a dreamy summer day in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco, where he’s filming another Guadagnino joint, Artificial, about the paradigm-shifting rise of OpenAI. Garfield will play founder Sam Altman, whose precocious gifts could be used to obliterate humankind as we know it. Between this and his turn in After the Hunt, Garfield has started to dabble in the dark side, and he is both exhilarated and a bit nervous about it. “I was intimidated by the project,” he says of After the Hunt. “I was intimidated by the character, which excited me. And it felt spicy. It felt very provocative as a piece.”

ECKHAUS LATTA Shirt, at eckhauslatta.com. ERL Crewneck, aterl.store. THE SOCIETY ARCHIVE Pants and Belt, available upon request.

Photo: Anton Gottlob

The role is his finest since Saverin in The Social Network, which introduced audiences to the Garfield who has shown up in some form or another in nearly every movie since: lithe and boyish and elfin, an aspiring adult in his black blazers and dress shirts. Unlike some traditional leading men, whose sharp jawlines and cheekbones could slice through steel, Garfield has always been more fuzzy and delicate, a forerunner of the slighter male stars of contemporary Hollywood, with a long neck that makes him seem fragile, as if that pretty head might just fall off. In After the Hunt, he looks sturdier, hungrier, darkly leonine with flowing hair and a mighty beard. He acts differently, too: lordly and assertive, a rake with a Nietzschean contempt for those he perceives to be beneath him. As he says in one scene, explaining why he is so confident of his professional and personal success, “Only the thoroughbreds have a chance of winning.”

Though careful not to conflate himself with his character, he says about Hank, “I think his argument is that great things are never done in the center. They are done at the edges. And you only really become worth your salt as a human being when you go down into the depths of your own humus. It’s not ascension; it’s descent.” It’s an interesting remark from someone whose characters have often aspired to the highest of ideals: kindness, loyalty, even saintliness. They’ve also rarely managed to be all that memorable. Hank Gibson feels like the crucial element that has been missing from a repertoire that has largely hit a single nice note. It suggests that perhaps it’s not possible to be a viable leading man without at least a hint of the menace lurking beneath.

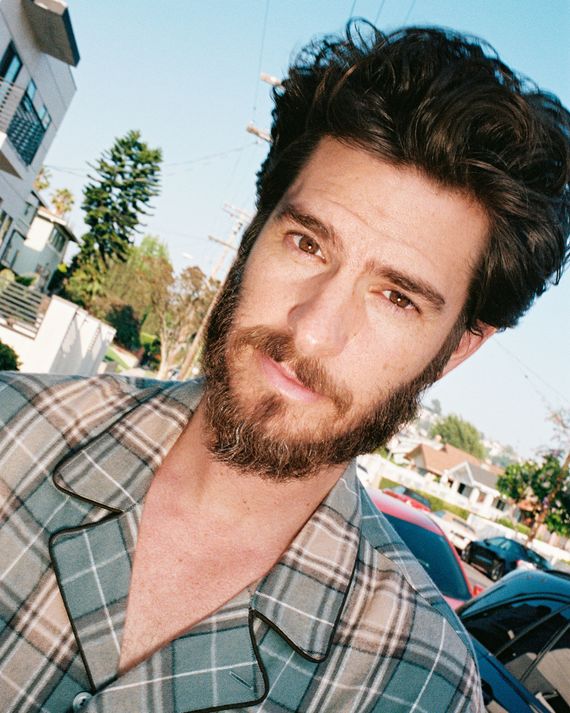

GAP Shirt, at gap.com.

Photo: Anton Gottlob

Garfield is not the only actor going against type in After the Hunt, which revolves around an ambiguous, drunken encounter between Hank and Maggie Price, played by Ayo Edebiri. Maggie says Hank violated her, Hank denies it, and caught in between is Alma Olsson, who is both Maggie’s mentor and Hank’s colleague and confidante. Alma is played with regal ferocity by Julia Roberts, who swears like a sailor, drinks like a fish, and stalks her classrooms like Lydia Tár, hurling insults at the coddled students who get under her skin and offend her brilliant mind with their pat ideas about social justice. Edebiri is her principal opponent, both sympathetic and frightening, a victim-cum-terrorist who weaponizes all the narrative devices of racial and sexual oppression to raze her elders’ lives to the ground.

The movie is the first time Garfield and Guadagnino have collaborated, but they have been circling each other for a long time. “He asked me to do I Am Love,” Garfield tells me, referring to Guadagnino’s ravishing 2009 picture showcasing Tilda Swinton as an older woman who discovers her true self in an affair with a younger chef. Garfield was to play her son. “I think he was on a layover with Tilda at Heathrow,” he says. “He asked me to have a meeting with them in this departure lounge. It felt surreal and decadent and very Luca, retrospectively. I wanted to do the film, but I didn’t have the time to learn Italian.”

When I ask Guadagnino about the actor’s moody brooding on set, he tells me, “I love intensity, but at the same time, I want to make sure what I do comes across in a light way.” He adds, “I realize we must have brought Andrew to a very thoughtful place, so I dared to say, ‘Hey, Andrew, is there something I can do to relieve your tension?’ It was more about my concern that something was wrong with him.”

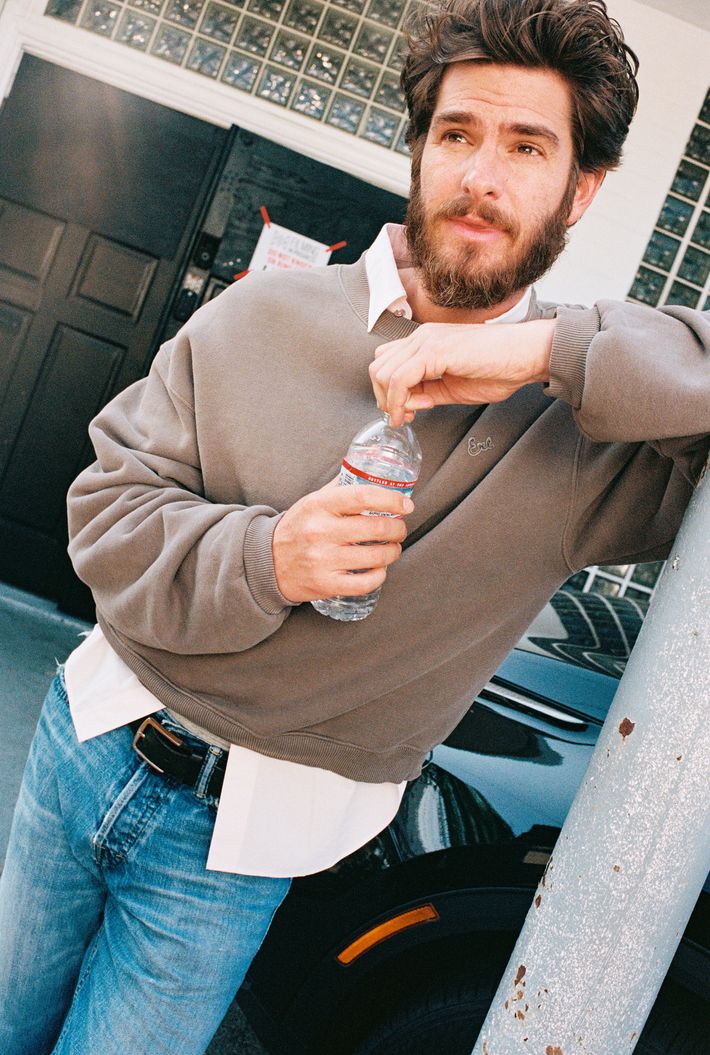

ACNE STUDIOS Jacket, at acnestudios.com. OFFICINE GÉNÉRALE Shirt, at officinegenerale.com. GAP Shirt, at gap.com.

Photo: Anton Gottlob

Guadagnino is a slyly provocative filmmaker, but After the Hunt is his first proper foray into the politics of identity after a series of movies that were simultaneously bold in their declarations and limited in their scope. The title of I Am Love is in essence an argument: that who we are lies dormant within us, waiting for a sensual spark to erupt through the strata of class, smash through conventions, and emerge into the light. Call Me by Your Name captures the world-reorienting moment when we admit that we have fallen in love and that this other person, of all people on earth, has come to represent our tastes and predilections and innermost desires — it could have been called I Am You. Love triangles are a common theme: The three tennis players at the center of Challengers might have been different people altogether, the film posits, if their relationships had only been configured differently.

After the Hunt reckons with how the external markers of identity define us, often over our protests — how maleness and whiteness, say, can be both a source of privilege and used against a person in the zero-sum battles of the culture wars. Or, as Guadagnino tells me, “I like the idea of power as a key to understand character and using character to understand the power that underlies our way of being.” The locus of these tensions is Alma, who is torn between her sympathy for her fellow woman Maggie, her intellectual affinities with (and sexual attraction to) Hank, and her own towering academic ambition, which itself is considered a defect because of her gender. But for all their bravado, all three characters stagger across the movie blindly, blown about by forces they don’t quite comprehend. In such a bewildering environment, Guadagnino asks, when the sense of self is at odds with how the world perceives that self, who can say who Alma or Hank or Maggie really are?

Garfield is clearly aware the movie risks being perceived as anti-woke, one of a number of new entertainments, such as Ari Aster’s Eddington, that are treating very recent history with a revisionist eye. It is as if a growing pocket of auteurist Hollywood, bucking against the industry’s championing of identity politics, is now convinced there was something extreme and embarrassing and even inhuman about that era. One could interpret the character of Hank, a libertine with large appetites and naked desires and a free mind, as a corrective at a time when disillusioned men are seeking solace in the sculpted arms of Joe Rogan and the misogyny of Donald Trump. At the very least, After the Hunt is poised to act as a stand-in for such debates, much in the way that a Sydney Sweeney ad became a vessel for so much cultural angst.

THE SOCIETY ARCHIVE Shirt and Pants, available upon request. CARTIER Watch, at cartier.com. JIMMY CHOO Shoes, at jimmychoo.com.

Photo: Anton Gottlob

Garfield and Guadagnino say they are merely exploring the truth, messy as it may be. “The pervasiveness of consensus, of mainstream thought, is that things can only be said in one way,” Guadagnino says. “I want to say it another way.” As Garfield sees it, “it’s the duty of the artist, and maybe one of the duties of being a human being right now, to find the thing that we point at outside of us and say, ‘Oh, well, that’s not me’ — to find where that does reside in ourselves.” The point of the movie, in other words, is not to claim that men like Hank have been unfairly canceled, even if it entertains that possibility; rather, it is to reflect the ugly impulses and hidden motivations within everyone.

Indulging in the seedier aspects of human nature required a lot of trust among the principals. “I saw in Andrew a real rigor about being malleable, a determination to go wherever he needed to go,” Edebiri tells me. “I was quite moved by it, and it gave me the green light to go there, too.” At one point, Edebiri says, Roberts joked that Guadagnino had assembled all of these incredibly charismatic, funny people to “be quite vicious to each other” and “do a lot of deep staring.” In an email, Roberts writes, “There is a lot of darkness to the story that we took on together and then just put away at the end of the day. All of us did that very similarly.” In one particularly difficult scene, Alma and Hank confront each other in Alma’s spare apartment. Garfield here is at his most dangerous and louche, waking from a nap on Alma’s bed like some feral beast who has been in hibernation — pantless, his wiry chest hair peeping out from a shirt whose two halves are barely clasped together by a single button. The subsequent tête-à-tête brings Alma and Hank’s latent feelings to the surface, a push-pull of revulsion and attraction, aggression and submission, that showcases Hank’s wants in all their unbridled vehemence. The scene was done in one take. “It was astonishing, actually,” Roberts says. “Pure Luca.” Guadagnino says nearly the entire movie was done in one take. “Why do you need to do more?” he asks. “I’m still trying to understand why filmmakers I admire do more takes than are needed when they have such great actors. I’m of the Robert Altman school. Very swift.”

For Garfield, the abrupt end to the shooting of that scene came as a relief. “It’s a horrible thing,” he says, “even if it’s all make-believe.”

BALENCIAGA Shirt, Pants, and Belt, at balenciaga.com.

Photo: Anton Gottlob

We leave the coffee shop and head toward Golden Gate Park, Garfield musing about the quirks of playing Sam Altman. (“I keep saying ‘like’ a lot. I wonder if that’s because of Sam — he says ‘like’ a lot.”) The Haight’s colorfully bedecked stores and restaurants are surrounded by tourists and the unhoused, like some fantasy neighborhood of gingerbread houses crossed with the fentanyl crisis. Garfield is attracting smiles and surreptitious glances and calls of “Andrew, love your work!” and he handles the attention, which I can attest is pretty overbearing even for a bystander, with grace and aplomb.

That has not always been the case. There was a time when he’d hold a piece of paper with a list of charities to his face when the paparazzi were around, a quixotic attempt to remain a normal person and convince Americans there are more important things in life than celebrity. There was a time, too, when he bared his heart to the press. In an interview with this magazine ten years ago, fresh off playing Spider-Man, you can practically see him writhing as the talons of fame sink into him. “I’m still fucked up in my own ways, and insecure, and scared, and don’t really know who I am,” he said back then, an honest admission that earned him tabloid headlines like “Andrew Garfield Snaps in Interview.” He has learned how to take control of his story, declining to divulge any details about his relationship with Monica Barbaro (who also stars in Artificial). He seems at peace, actually, even if he has a habit of casing his surroundings for overeager fans like a spy watching for an enemy agent on his tail.

“I’m happy because it feels that I’m on the edge of something,” he says. “I don’t know what edge I’m on yet, but it’s definitely an edge.” It’s a strange thing to say about a man who is 42 years old, but, like actors before him who have left their boyish personas behind as they transition to more serious work, Garfield seems like he has grown up. His earlier roles frequently involved an innocent awakening to the world’s horrors, whether it was Saverin realizing he has been outplayed by rivals who are more ruthless and cunning, or We Live in Time’s Tobias understanding that we do in fact all die. It is only in Spider-Man that the process of maturation is treated as ennobling and fun. With his determination to push himself into uncomfortable places, it’s as if Garfield is acknowledging that being a man is about much more than losing the boy inside us — that it’s about managing the sometimes voracious needs that materialize alongside empowerment.

MIU MIU Jacket, Pants, and Shoes, at miumiu.com.

Photo: Anton Gottlob

Not to mention ambitions. Altman exerts a ghostly presence over our conversation, just as the shadow of his company and its brethren darkens the Northern California landscape. “It’s hard to do this interview because I’m getting ramped up to start playing Sam,” Garfield says, “and it’s important for me to make it as truthful and as absurd as possible. I get taken over by the grip of creative responsibility when I start a project, so it’s hard to split my focus.” At one point, he breaks off a thought and starts staring at his wrists. “Sam does this weird thing with his hands when he talks. It’s like, palms up, but it’s a limp-wristed palms up, so I’m just thinking about that.” For research, he is reading Karen Hao’s Empire of AI and watching a lot of podcasts. He is leery of AI — “curious but horrified” — and the implicit assertion that everyone has to “get on this steamroller or be flattened.”

When I ask him if he is worried AI will take over the acting business, producing a more handsome version of Andrew Garfield who speaks with Andrew Garfield’s voice and replicates his mannerisms, he says his main concern is losing the real-world joys of his work. “Just the pure pleasure of getting together with a band of idiots and trying to make something that we all inject our souls into,” he says. “It’s like, what is it — what does dialectical mean?”

“When two things oppose each other and they synthesize,” I reply.

“Yeah. It felt like one of the most beautiful dialectical experiences. And it’s there for us all the time. You and I having this conversation,” he says. He describes a lunch where he and his friends were arguing about some subject, only for one member of the party to spoil it by getting the answer from ChatGPT. Another of his friends, crestfallen, said, “Oh, it’s the end of discussion. It’s the end of debate. It’s the end of discovery for human beings.”

“The debate is the point, right?” I say. “The answer is not the point — the point is to try to figure it out.”

“Exactly,” he says.

MAGLIANO Jacket, at magliano.website. GAP Shirt, at gap.com. HERMÈS Bag, at hermes.com. GABRIELA HEARST Shoes, at gabrielahearst.com.

Photo: Anton Gottlob

Production Credits

Photography by

Anton Gottlob

Styling by

Jessica Willis

Digital Tech:

Benoist Lechevallier

Photo Assistant:

Jorge Solorzano

Styling Assistants:

Brandon Michael and Austin Manigo

Grooming:

Christine Nelli

Tailor:

Susie Kourinian

Production:

GE Projects

The Cut, Editor-in-Chief

Lindsay Peoples

The Cut, Photo Director

Noelle Lacombe

The Cut, Deputy Culture Editor

Brooke Marine

The Cut, Photo Editor

Mara Rothman

The Cut, Fashion Market Editor

Emma Oleck

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the September 2, 2025, issue of

New York Magazine.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now

to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the September 2, 2025, issue of

New York Magazine.