The Athletic has live coverage of the U.S. Open 2025.

FLUSHING MEADOWS, N.Y. — The latest pivot point in Iga Świątek’s tennis career happened when no one around her expected it, in May of this year.

For most of the six months leading up to the Italian Open in Rome, she had been going through the motions of trying to evolve as a tennis player and as a person.

She had hired Wim Fissette in October 2024. The renowned coach, who had helped guide Naomi Osaka and others to the top of the tennis world, had spent those six months trying to get her to restore the patient but tactically aggressive tennis of her early career. Daria Abramowicz, her sports psychologist and a key member of her team, had spent many hours on long talks with Świątek. She was trying to get her to leave her one-month anti-doping suspension for taking a contaminated dose of melatonin, a sleep aid, in the past.

The 24-year-old six-time Grand Slam champion wasn’t really listening to either of them. She heard them out, nodded plenty and showed fleeting signs of change. But when she walked onto the court and when she decompressed off it, she reverted to form.

In matches, her first thought was to hit the ball as hard as possible, no matter how hard it was coming over the net. In her down time, her thoughts would drift back to last fall, when she tested positive for trimetazidine (TMZ), a banned substance.

The ITIA accepted her explanation that a contaminated batch of melatonin was the source of the positive test. Świątek submitted her medications and supplements to independent laboratories, alongside unopened containers from the same batches and hair samples. She missed two months of competition while provisionally suspended, losing the world No. 1 ranking to Aryna Sabalenka.

For months, as she sought her championship form to win a tournament, she kept going back to the unfairness of it all. She reached the quarterfinals or the semifinals in all seven tournaments that she played before the Italian Open, but she also saw four title defenses thwarted.

And then Danielle Collins smoked her in straight sets on Rome’s red clay, a surface where she dominates. Nine days earlier, Coco Gauff had blasted her off the court in Madrid; Jelena Ostapenko had beaten her in Stuttgart three weeks prior. Świątek, the queen of clay, was without a trophy on the surface for the first time since 2019.

In retrospect, that might be the best thing that ever happened to her. Two of those four title defenses had been on hard courts, in Doha, Qatar and Indian Wells, Calif. Świątek has seven WTA 1000 titles on the surface; she won the U.S. Open in 2022. And no matter what anyone told her, she figured that she could just do what she did in the past, but do it better, even if Fissette and especially Abramowicz — who espouses the values of a mindset focused on growth rather than results — told her otherwise.

It was when she hit rock bottom on her best surface that she started to listen. In a series of meetings with Fissette and Abramowicz ahead of the French Open, she took in what some other people that they all respect had to say. Now she is a Wimbledon champion, back to world No. 2 and back in the U.S. Open quarterfinals, who is texting Fissette straight after lancing Ekaterina Alexandrova to book a practice court for more work and more listening ahead of a Center Court rematch with Amanda Anisimova.

One of those people she listened to before Paris is the greatest skier in the world.

“Mikaela Shiffrin said that every time when she skis, she thinks about winning, she literally loses,” Świątek said on the London July afternoon that she lifted the Rosewater Dish, reaping the greatest possible reward from an evolution based on not thinking about them at all.

“I’m kind of similar. I think, you know, the best things will happen to you when you least expect them.”

During a recent interview in Mason, Ohio, where Świątek claimed her second title since those hinge moments after Rome by winning the Cincinnati Open, Fissette described the journey toward this more patient and tactical version of Świątek.

“Tennis is always getting better, so you have to make sure you’re getting better,” he said.

“Copying what you did the last year and just expecting that things will be exactly the same was not the right mindset. It was hard for her to realize that. And after Rome she was more focused on just developing as a player.”

Fissette and Świątek started working together when her immediate tennis future was still murky. Fissette didn’t care. Osaka, his charge for much the past five years, had decided to part ways with him. He was a free agent, and Świątek had jumped on the chance to hire him after she had decided to part with Tomasz Wiktorowski.

Fissette told Świątek that she didn’t need to be a hero on every shot. She hits with amazing, heavy topspin. Almost no one on the tour can match her on either wing. Why not use that spin and that advantage to change the height of the ball over the net and push her opponents further behind the baseline, to open the court for an easier winner?

She can play with more patience than most players who can’t generate her prodigious revs. She can accelerate over the ball and land it with plenty of margin, rather than blasting flat and true for the lines to win points. And she can use that advantage to construct points, rather than crushing them, climbing the ladder to the front of the court to finish off an opponent hopelessly scrambling far behind the baseline.

Like everyone else, Fissette had watched Świątek win her maiden Grand Slam title at the 2020 French Open, when she was just 19. She played with so much variety then, finessing drop shots and relying more on sharp angles and arcing strokes than flat, linear power. Wiktorowski had simplified her into a first-strike, all-out aggression machine. It won her four majors, but also stunted the qualities that separate her from other great players. The peerless footwork. The impregnable defense. And that patient, high-margin, sideline-breaking spin, that takes opponents’ legs and leaves them feeling like a puppet on a string.

“The beginning is always easy,” Fissette said, “when the players are open.”

Wim Fissette and Iga Świątek’s partnership has blossomed in recent months. (Robert Prange / Getty Images)

Świątek listened at first, and Fissette’s ideas worked. She matched her best result at the Australian Open, coming within a point of the final and losing in a gripping tiebreak to eventual champion, Madison Keys, who had the best two weeks of her tennis life.

But then Świątek started to play tournaments she had previously won. When she didn’t successfully defend the titles, Fissette watched as she reverted to the habits that had left her without a cushion on off-nights, especially when under scoreboard pressure. When swinging hard didn’t work, she would just swing harder, sending the ball flying off the court or into the net. And much like late-2024 Carlos Alcaraz during his in-match troughs, her serve lacked the precision and effectiveness to act as a release valve when her ground game deserted her.

As frustrating as it was to watch, Fissette understood what was happening. He has been through just about every coach-and-player dynamic that exists.

Half of Świątek’s brain was telling her to escape danger by doing what had worked in the past. The other half was trying to process the information Fissette was giving her and use it to escape into her tennis future. She knew this herself, even early in their partnership, with the pattern of swinging hard under stress having taken hold back in 2024.

“I see my game every day,” she said during an interview. “It’s hard to see the changes because they’re little. I know. They only seem big on a bigger horizon.”

He also sensed another problem that often goes overlooked in such an international sport. Świątek had always worked with an entirely Polish team. Now she and Fissette were communicating in their second languages. He could tell that sometimes, she couldn’t totally understand what he was saying, especially when he used the same words he had used with Osaka when he delivering technical instructions.

Fissette, 45, felt like he was failing Świątek, because he sensed her frustration when her results didn’t measure up to her lofty standards. She’d always been a good student. She wanted to learn.

“She wants to be, let’s say, corrected a lot,” he said. “She wants to be coached very intensely. And to find that ideal coach-player relationship, we needed some months to get on the same line, finding the right words at the right moment.

“We needed some time. I think it’s normal.”

Fissette wasn’t exactly sure how they were going to get past their obstacles, but he believed that they would. Then Rome happened, and he and Abramowicz saw that they had an opening. Świątek always got good grades in school. Tennis delivers grades in the form of wins and losses and rankings points, and Świątek’s grades were slipping.

“We had several meetings about a different mindset, just focusing on becoming a better player and evolving and adding stuff to her game,” he said.

“If you want to stay at the top, that’s what you have to focus on and results will come after. You cannot just focus on the results.”

Świątek also began to let go of the boulder of the anti-doping process that had forced her out of tournaments and cost her ranking points. “For many months I just couldn’t get over some stuff that happened,” she said.

But once she got to Roland Garros, she put it out of her mind.

“I managed to not think about and not come back to this stuff anymore and not think that the world is not fair or something. Obviously I’m not in a place to say that the world is not fair, because people have it much worse.”

Then she arrived in Paris, the site of her greatest success, as a four-time winner and the defending champion. She was also the No. 5 seed, with few expectations. She said she was not the favorite, regardless of her previous success.

That was fine with Fissette, because he could see she had opened her mind to new ideas. In one practice before the tournament, she ended up on the court with Alejandro Tabilo of Chile. Like most top women, Świątek often hits with men. She’s fine with the pace and used to the weight of their shots.

Tabilo’s serve was a different story. At first it kept whizzing past her. Świątek, whose ability to turn just about any serve into a feast is a trademark, had her toes on the baseline, another old habit that had started to cause her more problems than it won her points.

Fissette told her to move back. She started landing returns in the court. Then she got to the French Open quarterfinals against Elena Rybakina, and got hammered 6-1 in the first set after standing too far up and too central to the 2022 Wimbledon champion’s powerful serve, especially the one she can swing away past a player’s forehand.

In the second and third sets, she moved diagonally backward. She won. She did it again to Rybakina months later, at this year’s Cincinnati Open. And while she lost to Sabalenka in the semifinals in Paris, Fissette thought that it was a great result. Świątek wasn’t just playing differently; she was adjusting her tennis in real time, while sliding across the clay like a figure skater, just as she always does.

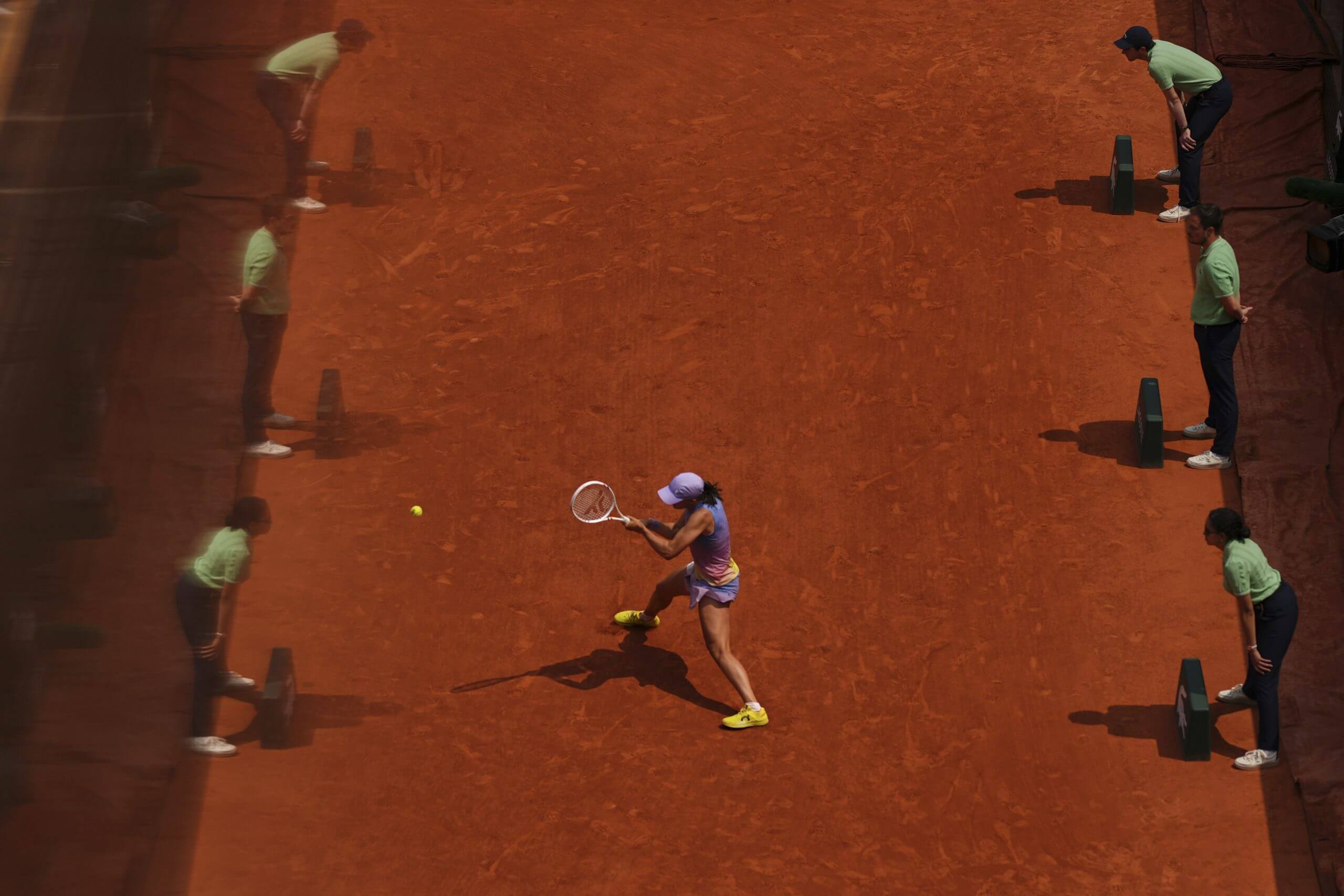

Świątek has reembraced playing with margin and patience, as well as introducing deeper return positions. (Aurelien Morrisard / AFP via Associated Press)

“We really felt like she was getting back to the real Iga we love to see,” he said.

The earlier-than-usual loss at Roland Garros also carried a hidden advantage. It shifted her focus to Wimbledon and the grass, the surface where she felt the most discomfort, with extra days to rest and without the emotional exhaustion of playing in a Grand Slam final. But even at Wimbledon, her results were hardly disastrous. Her third-round exit to Yulia Putintseva was the apex descent into ball-bashing when under duress. In 2023, she reached the quarterfinals and ran into Elina Svitolina, who was on a dreamlike run; in 2022 and 2021, Alizé Cornet and Ons Jabeur, crafty characters able to exploit holes in a player, took her down.

That discomfort meant that she was more open than ever with Fissette, whose players had enjoyed great success at the sport’s most important tournament. He coached Angelique Kerber when she won in 2018. He coached Sabine Lisicki to the final five years earlier.

Growing up in Belgium, Fissette often played indoors on carpet, a slick surface that can behave a lot like grass. The footwork was similar, but it was footwork that Świątek had never really practiced. The grass also brought opportunities for her to use the variety that she had kept inside her hands for much of the past three years. So after she played a warm-up in Bad Homburg, Germany and reached the final, she skipped another in Berlin for more practice, focused on making her better on grass long-term.

The payoff came quickly. At Wimbledon, Świątek looked like she’d always been a natural on grass. She chipped returns back at her opponents’ feet. She used drop shots. She sliced her backhand. But most of all, the technical adjustments that she had been working on for months started to pay off in concert with her mental focus patience and tactical manipulation. Świątek turned into something of a serve bot at Wimbledon. Her forehand was more compact and more devastating. She joysticked opponents around as she had done on clay for years. In the final against a frozen Anisimova, she was untouchable in a 6-0, 6-0 win.

She got the ultimate prize for it, but the triumph at Wimbledon brought more than a nice trophy and about $4 million.

“It will give me a lot of motivation, I think, because I feel like I developed my game,” she said. “And I haven’t felt like that for a while, maybe except when I was at the Australian Open.”

Fissette hopes it’s only the beginning. He wants to slowly bring back all the variety she once played with. He wants to see her hit more drop shots and finish more points at the net. Rewatch Świątek’s most famous win of her 2020 French Open run, a dismantling of No. 1 seed Simona Halep, and see a web of finesse and serenity weaved around the brutal topspin.

“She’s very skilled and she’s got good hands, but she hasn’t used those skills the last years,” he said. “She has learned to have this efficient, disciplined game. But at the end, you have to keep surprising. Otherwise players will understand exactly how you’re going to play. So you have to keep surprising. That’s the goal.”

He also wishes that Świątek didn’t have to have had such a rough go to get from there to here, to change from the player she was to the one she wants to be.

“Sometimes it just takes a hard time,” Fissette said. “It takes something that happens to make you do it.”

(Photo: Timothy A. Clary / AFP via Getty Images)