explore the architecture office of a minimalist icon

A landmark opening is set to take place in Marfa, the small Texas town whose transformation into an ‘art destination’ was famously led by the legendary Donald Judd. While he is among the most important American artists of the minimalist movement, it is less commonly known that his practice extended beyond sculpture and furniture and into architecture.

Judd had moved from New York City in the 1970s to the remote town which dots the endless high desert. In the decades to follow he was busy establishing large-scale art spaces and undertaking ambitious historic preservation projects. His many endeavors include an office in the heart of town which ultimately became his working architecture studio.

The office occupies a two-story brick structure which was first built in the early twentieth century before its overhaul by Judd and his team after acquiring it in 1990. Its recent restoration follows a seven-year effort that began in 2018 and paused after a fire in 2021. Throughout it all, the design team’s approach is driven by Judd’s own principles — respect for original materials and thoughtful adaptation to context. The renovation of Donald Judd’s architecture office in Marfa has reached completion and will reopen on September 20th, 2025.

Architecture Office, Judd Foundation, Marfa, Texas | image by Matthew Millman © Judd Foundation

a restoration driven by donald judd’s design principles

The reopening of the Marfa office is led by Texas-based studio Schaum Architects along with the Judd Foundation, which sees to the preservation and revival of Donald Judd’s architectural works. Through the project, passive cooling strategies, a rooftop solar array, and sustainable insulation methods are integrated into the original structure. Its historic spirit, meanwhile, is maintained and celebrated.

Interiors become gallery spaces for the display of Judd’s plywood and metal furniture, drawings, physical models, and archival material. Visitors traveling through Marfa are invited to explore these rooms to experience the depth of Judd’s architectural practice in the spaces where it came to life.

Ahead of the office’s September 20th reopening, designboom spoke with Rainer Judd, President of the Judd Foundation and Donald’s daughter, about the project’s place within his legacy and its role in the ongoing story of Marfa.

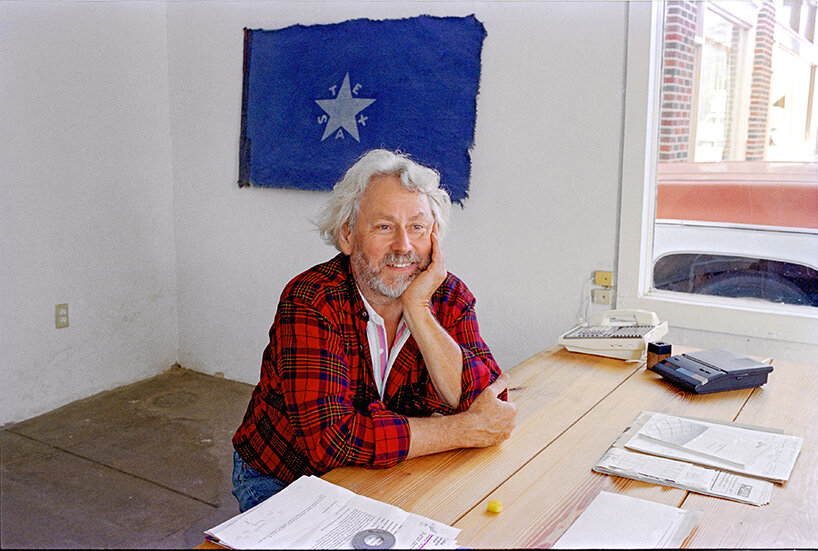

Donald Judd in Marfa, Texas, 1993 | image © Laura Wilson, courtesy Judd Foundation

dialogue with rainer judd

designboom (DB): Can you describe the spirit of Marfa through your eyes, and through the eyes of Donald Judd? How has it has evolved since his first presence there?

Rainer Judd (RJ): Marfa has a small-town history that is the core of its spirit — generations of individuals and families have helped shaped this before Don. From its days as a military outpost to its period as a cattle town, through the de facto segregation period against Mexican American residents, through its economic up and downs, it tells the story of change in the southwest, demographically and economically. Before it was settled as a town, this region has been inhabited for thousands of years.

For Don, Marfa was a place to install his work, a place to be in and care for the land, and to think. Inadvertently, it was an opportunity to do something locally that did not go against the nature of the place. He was against Marfa becoming a cattle town museum, and an art town as well, he was against the idea of an artist colony.

Today Marfa is considered an ‘art destination,’ and it was not when Don was living there. It is our responsibility to show up to the challenges we’ve helped create. I think for the work of the Foundation it is important to consider Marfa in an everyday context, of a small town, with us being one of the many individuals contributing to the next chapter of the place’s history.

Architecture Office, Judd Foundation, Marfa, Texas | image by Matthew Millman © Judd Foundation

DB: While he is known first as an artist and designer, he famously had many built and unbuilt works of architecture. How did these different creative disciplines intersect for him?

RJ: Art and design were individual parts of a whole, but you can see how they work with architecture, they all deal with space. In his writing on all of these — art, architecture, design — he states that the need to preserve and install his work in spaces that he considered appropriate and the invention of his work, were two primary concerns that ‘joined and both tend toward architecture.’ Concerned with the space surrounding his art, this led to repurposing buildings and envisioning future ones for different purposes.

That being a given, he understood that art did not have to concern itself with function the way architecture and design do. He emphasized that architecture was not art, but that did not mean that it could not be artistic or cultural the way that many objects and structures clearly are.

His concerns with scale, materials, form, and quality were the points at which these disciplines intersected. And also dignity, which he refers to often in writing and in interviews about architecture and art. The dignity of spaces, for living and for working, he believed good buildings had that quality. And of course, the inherent dignity of art, which led to his concern with its preservation and proper installation.

Architecture Office, Judd Foundation, Marfa, Texas | image by Matthew Millman © Judd Foundation

DB: How do this building and its restoration illustrate his architectural and artistic vision?

RJ: Considering the historic and spatial context of buildings, understanding their original structure and function was important to Don. When he bought the Architecture Office, one of the first things he did was sandblast the facade, he wanted to return the building to its original condition. This action takes into consideration the town, the style, and the time in which it was built. He respected original thought, labor, and materials. He was interested in not wasting this. He understood that the building could serve other purposes and even have his ‘unusual furniture’ inside but structurally it should be returned to the context, or as he would say the ‘situation.’

This aspect of understanding historically, spatially, and culturally where one is and what can be done with the available materials and resources, can be seen in both his art and architecture practices. And it was also what guided the Foundation’s work in this restoration project. The building needed to be up to date to protect the installed collection and the integrity of its structure, to adapt to the desert climate and be energy efficient, but whatever had to be done had to consider the existing situation and how it fit into the broader history and community in Marfa.

Architecture Office, Judd Foundation, Marfa, Texas | image by Matthew Millman © Judd Foundation

DB: What discoveries were made during the team’s environmental condition studies, and what were some challenges in bringing the building back to life, especially with the harsh Marfa climate?

RJ: The building has beautiful details that were able to be maintained and preserved or rebuilt after the fire — from the archway on the second floor, to the press tinned ceiling, to its double hung windows, to the framing of the building. Following the fire, we had the opportunity to have new conversations to the possibilities within the structure.

The building itself, built circa 1915, was structured with a lattice of wood beams across the attic ceiling so it all had to be rebuilt. This provided our talented project team with a time period to consider how to do it better, more efficiently, with the time of one hundred years to reflect upon. We installed a system which I am excited about, which reflects the ‘technologies’ humans have used for thousands of years in desert climates in which the cool night air flushes the building.