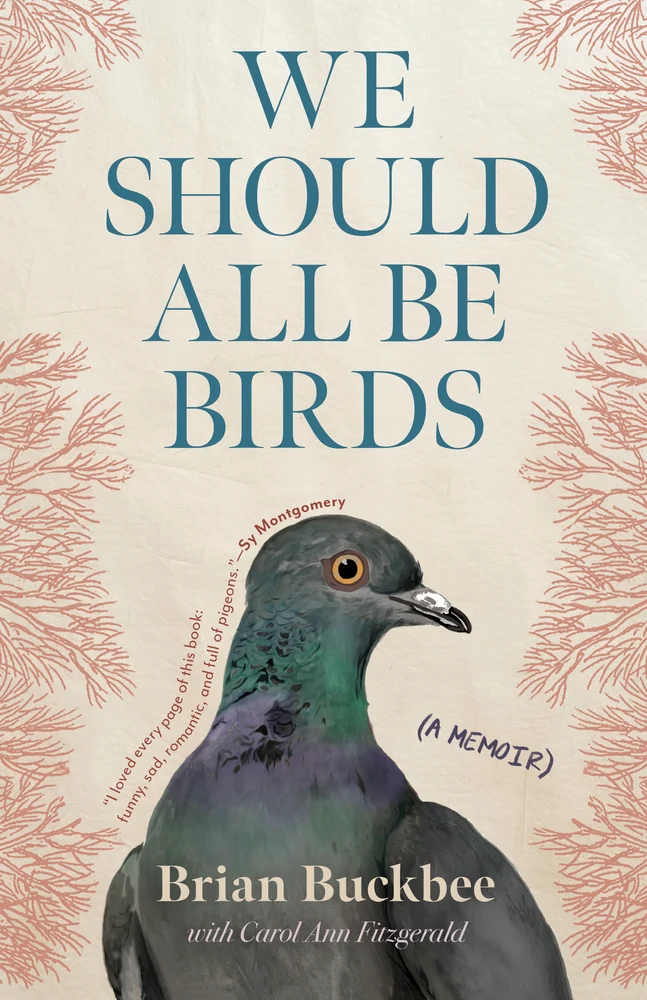

I don’t want to say human-animal relationship stories are to the book world what Christmas is to the Hallmark Channel, but there is a trap waiting for animal-loving writers where redundancy, sentimentality, and smarminess dwell. Perhaps I avoided that trap in We Should All Be Birds, a memoir I wrote about a wild pigeon named Two-Step, because I didn’t actually write it. (A health condition forced me to dictate parts of the story, and my coauthor helped me turn them into a book.) At their best, animal stories don’t just tug at the heart but shift how you see the world. My relationship with Two-Step did that for me, in ways both profound and hilarious.

Whether or not the writers on this list set out with the intention of saying something new or different about a person’s relationship with a wild animal, they did. (Like me, some of them may not even have planned to write a book, but the animals didn’t give them much choice.) As a result, each writer carved out their own niche—proving, as I found when illness contracted my world, that there is an infinite amount of space in even the smallest of circles.

They say you travel somewhere not to understand the place you are going to but to understand the place you came from. These stories show how our connection to wild creatures can help us understand animals, and perhaps more importantly, ourselves and, in the process, learn to live, thrive, and heal.

The Hawk Book

H Is for Hawk by Helen MacDonald

At the outset, it is important to note a couple of oddities. First, training hawks is called falconry. Second, I—a pigeon rescuer—am writing favorably about the pigeon’s enemy number one. (Tied for second are the raccoon and the cat.) MacDonald writes half for the head and half for the heart. A scholar and professor, she explores the biology, history, and mythology of predatory birds, especially the goshawk, one of which she adopts (and names Mabel). At the same time, she struggles to cope with the sudden death of her father, who also happened to be her childhood falconry buddy. Goshawks are extremely sensitive by nature, so MacDonald must observe her adopted bird with patience and a keen eye. Not only do readers get to see this beautiful creature in all its detail, but MacDonald also turns that same, trained eye inward, helping herself (and the reader) understand the complexities of loss.

The Rabbit Book

Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton

People tend to think hares are the same as rabbits, though they are a very different species. Among their differences is that a wild hare is incredibly difficult to keep alive. On a walk one day, Chloe nearly steps on a newborn baby hare. What to do? Leave it so if its mother returns, she will find it easily? Move it into the grass where the mother might not find it? Or bring it home? In an act that will prove to be a gift to readers, she decides to take the young hare home.

From the start, Chloe’s goal is to NOT get close to the hare, literally. The biggest threat to a young hare is stress, and nothing causes a hare more stress than being handled and restrained. So Chloe holds a cloth in her hand before she picks up the hare to feed it from a syringe. She abandons early attempts at confining the hare and lets it have free rein in her home and garden.

Adding to the appeal of the book is Dalton’s understated crisis of her own. Previously an urban dweller consumed with her work in government, the pandemic forces her into a new life in the countryside. Though Dalton tries to maintain her old pace and lifestyle, she finds that the noise and activity are upsetting to the hare, so she begins living on the hare’s schedule and discovers a different pace of life. She doesn’t wear makeup, doesn’t watch the news, and doesn’t use lights in the garden at night. “It was excessive, it was absurd, it was beautiful,” she says. She realizes she has been waiting for life to go back to normal, but if this one hare can provide so much meaning and joy, what else might be awaiting her if she turns away from her old, hectic life?

The Octopus Book

The Soul of an Octopus by Sy Montgomery

In this exploration of the only eight-armed creature in the world, the reader will learn that the compellingly strange octopus has three hearts. The reader may need three for themselves, too, because Montgomery writes so beautifully about the mysterious cephalopod that a couple of theirs might just burst. With a background in journalism and having authored many books about other creatures (tigers, apes, dolphins, etc.), Montgomery is often referred to as a “popular naturalist,” and she has developed a writing style that is familiar and authoritative, funny and smart, and totally accessible. Over the course of the book, the popular naturalist gets to know several octopuses. (And, yes, octopuses is the plural of octopus, as is “octopodes,” which is also correct.) What stands out is Montgomery’s description of how these two creatures (human and octopus) have seemingly endless curiosity about each other. She becomes well acquainted with four different octopuses as the story progresses, and it turns out each one has its own personality. Using the term “personality,” though, is itself loaded, because animals, even the inquisitive and alluring octopus, are not people.

We learn from Montgomery that each arm of the octopus is essentially its own brain, capable of thought and emotion, and when she visits the aquarium and puts her arm in a tank, the resident octopus—whether it is Athena, Octavia, Kali, or Karma—will move its suckered arms across Montgomery’s un-suckered arm, sometimes blushing, sometimes retreating to a corner or tightening the embrace. And with each encounter, our estimation of this unique, marvelous creature grows, and we gain a greater sense of the depths of our compassion.

The Snail Book

The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elisabeth Tova Bailey

This is a memoir that crawls along at a deliberate pace—but it is far from slow. Pulling off that feat speaks to the writer’s craft and her scientific eye, since most of the book takes place with one character (the writer herself) confined to her bed, and the other (a forest snail) confined (mostly) to a terrarium that sits on a bedside table. The book is both reverie and revelation. (A single room? A snail? Really?)

The illness that incapacitates Bailey is so extreme that she can rarely leave her bed. Her visitors are few, but one brings a pot of violets, and serendipitously, this pot has a gastropodic stowaway. Grieving her busy former life—which included plenty of friends and plenty of time in the garden—Bailey turns her attention to the shell-covered, slow-moving creature who is living out its life beside her.

Such is Bailey’s curiosity (and what turns out to be the fascinating lives of snails) that it is easy to forget how extreme her illness is and how much suffering it brings. She launches into an investigation of all things snail, including a twelve-volume book by early naturalists, and along the way we learn things like how many teeth a snail can have (thousands) and how utterly complex snail slime is. This is not the voice of a person removed from the world but rather the voice of a person who has a new, strange world brought to her.

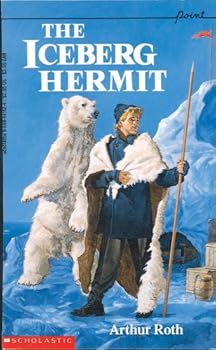

The Polar Bear Book

The Iceberg Hermit by Arthur J. Roth

Yes, this is a YA book, and yes, this book can help a child fall in love with reading (as it did for me when I was around ten years old). While not a memoir, it is the true (or true-ish) story of a young whaler in the 18th century who is the sole survivor of a shipwreck. Survival in the Arctic seems unlikely, but Allan Gordon gets lucky when the sunken ship, now turned belly-up, becomes frozen in the ice. This bit of fortune provides Allan with shelter, warmth, food, and…rum. Lots of rum. The isolation and freezing temperatures are not enough to numb the existential pain, and his turn to self-medication shows young readers that seemingly black-and-white issues are often filled with shades of gray.

Allan’s second break comes when he befriends an orphaned baby polar bear. He names the bear Nancy after his beloved, whom he left behind and yearns to return to. This creature, who he had been taught to fear, becomes a companion and the answer to his existential distress.

Allan and Nancy have numerous adventures, including encounters with creatures that want to kill him, and creatures he has to kill, and a fortunate run-in with Eskimo people he has to decide whether to trust or not. What struck me at the time and sticks with me all these years later is how much companionship a creature that we may not have thought much of before (or would have feared in an encounter) can provide. Though Allan longs to return to his home, nature finds a way to impart a valuable, lifelong lesson: if you can’t be with the one you love, love the one you’re with. (Even if it is a polar bear.)

The Owl Book I

The Wise Hours by Miriam Darlington

Reading is a migraine trigger for me, and as a result, I have only read two books in the past half dozen years, and this is one of them. I have no regrets about my choice. Darlington is a poet, and she has to be in order to describe owls in the way they deserve. Owls are shy, often invisible when they are right in front of you, and silent as they glide over a field where poor, scurrying creatures live. As Darlington canvasses the UK countryside and beyond in pursuit of owls and owl lore, she has to reckon with the health struggles her fellow explorer and helper is dealing with. That helper, Benji, is also her son, and the mysteries of his illness seem to mirror the mystery of the owl. Darlington not only writes gorgeous, rhythmic sentences, but her mastery of rhythm may be what helps her tune into the rhythms of the natural world (and in particular the habits and habitats of owls).

The Owl Book II

Alfie and Me by Carl Safina

In Alfie and Me, behavioral ecologist Carl Safina recounts a transformative year spent caring for a rescued baby owl during the COVID-19 pandemic. Though Safina has spent a lifetime working with wildlife, this tiny, downy creature—Alfie, a “ginger” Eastern screech owl who at one point is the length and color of a sweet potato—touches something deeper in him.

8 Books about the Interdependence Between Humans and Animals

Erika Howsare, author of “The Age of Deer,” recommends nonfiction about our coexistence with the creatures around us

Apr 2 – Erika Howsare

Reading Lists

As Safina tells the story of Alfie’s rehabilitation, he seamlessly weaves a fascinating tapestry of science, history, philosophy, and personal experience. He also conveys his abundant (and infectious) love for Alfie without a drop of sentimentality. As he prepares (and delays) Alfie’s soft release into a perilous freedom, Safina considers the bond they’ve formed and the difficulty of letting her go, asking himself: Should I open the door? Saying goodbye is complicated, but of course he does.

We won’t spoil the outcome, but Alfie’s part in it is uplifting. The human part is less so. Despite the charming relationship between these two gentle souls and their vibrant connection with the many beings in and around their Long Island backyard, the author makes sure we remain aware of greater threats to all life. As this clear-eyed scientist, guided by deep compassion, has said: “Technology won’t save the world, but our hearts may. And our hearts must.”

The Fox Book

Fox and I by Catherine Raven

It appears that Raven, who has the fortune of having a bird for a last name, has made a deliberate choice to live a solitary life. As she says, she is alone but not lonely. She is “uncomfortable with dialog” and opts for “disappearing into the woods” to avoid answering questions that cause her anxiety, especially those related to her parents and her alone-ness. She is a biologist and a teacher of naturalist history, and she is well-trained in the close examination of the living things she encounters. She has a fondness and curiosity for all of them, not just the fox who routinely visits near her cabin but also the trees, weeds, flowers, magpies, voles, and even a black widow spider.

Early in her “relationship” (her chosen word) with fox, Raven is warned by a colleague that her non-interactions are okay “as long as you’re not anthropomorphizing.” Apparently, attributing human characteristics to an animal is THE cardinal sin in natural biology. But even in a moment when her training says she should not allow an animal into her “social circle,” she wonders if she is “imagining fox’s personality.” The reader feels a tension here, one that reveals Raven may not be as completely at peace with being alone as she claims.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.