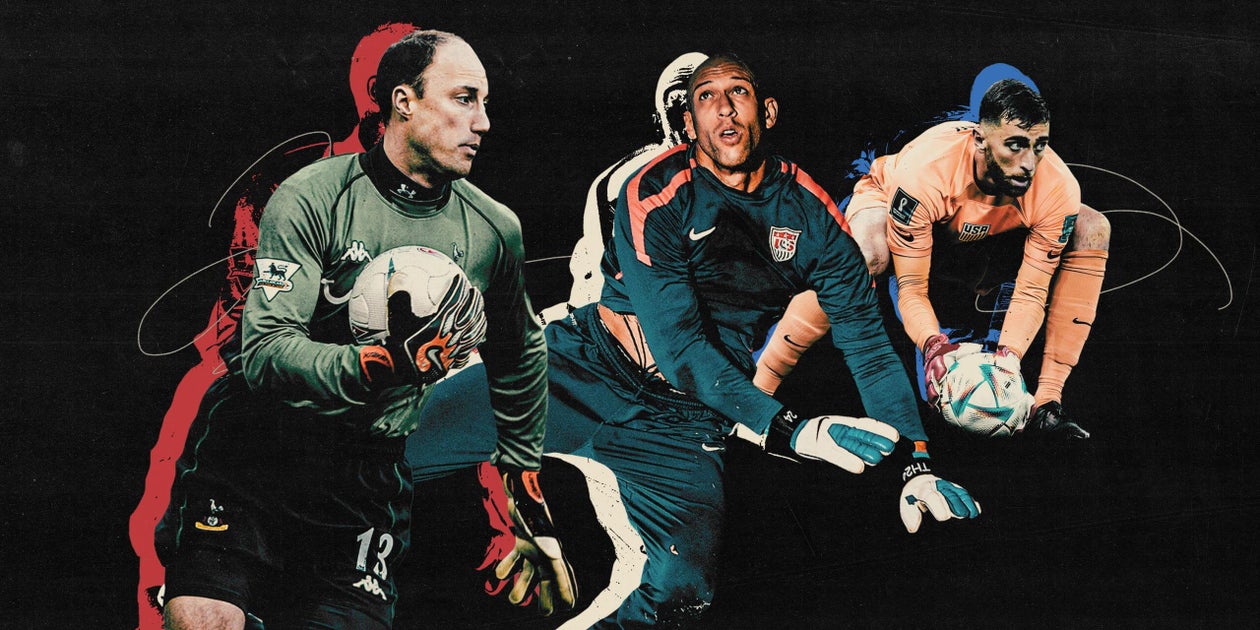

To many soccer fans, the dependable American goalkeeper was once as much of a national staple as fast food drive-thrus and podcast feuds. From 1995 to 2016, at least one Premier League club entrusted its last line of defense to a United States import. These men were beloved for being as committed to keeping clean sheets as maintaining their shaved heads.

Yet with the 2026 World Cup next in the queue, the USMNT is under intense pressure to find a starter – and is hard-pressed to feature a backstop such as Tony Meola, Brad Friedel, Kasey Keller or Tim Howard. Players who gave solidity to the USMNT at World Cup campaigns and were safe custodians at the club level.

“What we’ve had is a sort of changing of guard a little bit,” said Jack Robinson, U.S. Soccer’s head of goalkeeping. Robinson, whose CV also includes time with Manchester United and the FA, assumed the role in August 2024 fresh off of six seasons at Liverpool under Jürgen Klopp.

“With Mauricio (Pochettino) coming in and his staff, there’s a real onus from them to say that whoever is playing, whoever’s in form, whoever’s performing well for their team, will have an opportunity to come and play for us. I think that it’s up for anybody to come and try and take that No. 1 shirt.”

It can’t be comforting, though, that just over nine months from the World Cup kicking off in North America, Pochettino is still testing new options with a dwindling number of warm-up games left before the opening match. And it all leads to one simple question with a multilayered answer:

What happened to the once-mighty American goalkeeper?

“I think we were spoiled for a very long time,” Howard told The Athletic. “It’s an interesting question, one that I get asked way more than I’d like, because you’d like to see more American goalkeepers have success abroad.”

The U.S.’s grand return to the World Cup in 1990 provided a breakout moment for a few players; even more would get the star treatment once the tournament came stateside in ’94. Among the most popular faces was Meola, who played 11 games with Brighton after Italy 1990 but whose legacy was crystalized in MLS and across 100 USMNT caps.

Tony Meola was one of the stars of the USMNT’s 1990 and 1994 World Cup teams. (Photo by Russell Cheyne/Allsport/Getty Images)

By keeping the USMNT competitive in 1990 and helping send the hosts to the knockout stage in 1994, Meola set a standard that helped clue the world to a bevy of his successors.

Coming up as an Aston Villa fan, Aron Hyde — who was a goalkeeping coach on Gregg Berhalter’s U.S. staff from 2020-2023 — came to admire the exploits of “the Brads,” as he calls them in a conversation with The Athletic. The summer of 2008 brought both to Villa: Friedel, the veteran who had already logged over a decade of starts with Liverpool and Blackburn Rovers; and his understudy, Brad Guzan, brought over from since-defunct MLS franchise Chivas USA.

To Hyde, it wasn’t a source of anxiety to trust an American in goal. It was sensible.

“It’s the stereotypical, quintessential things that American sports and upbringings give: hand-eye coordination, just the natural athleticism that is prevalent within Americans is well-suited,” Hyde said. “And then just their demeanor, presence, personalities: confident and able to deal with the pressures that come in the Premier League.”

The pair combined to make 256 league starts for the Villans. Their tenure was far from an anomaly.

Juergen Sommer came first, joining Queens Park Rangers in 1995. Keller made his Premier League debut in 1996-97 after four years with second-division Millwall, making 201 starts for four clubs. Howard arrived in 2003 and made 431 Premier League appearances, making the PFA Team of the Year in 2003-04 with Manchester United before becoming an icon across a decade at Everton. A model third-stringer for the USMNT, Marcus Hahnemann was first-choice with Reading and Wolves across his 12 years in England.

The trend reached an abrupt end when Howard returned to MLS in the summer of 2016, while Guzan followed him across the Atlantic a year later. The USMNT saw its one-time bounty of Premier League starting goalkeepers deplete entirely.

Matt Turner has fallen out of favor as the USMNT’s No. 1 goalkeeper (Photo by Nick Tre. Smith/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images)

When Zack Steffen and Matt Turner were signed by Manchester City and Arsenal, respectively, they were viewed as dependable backups who could start cup games and give the preferred option a good sparring partner. Fans of their clubs need little reminding that Steffen and Turner struggled with on-ball decision-making; both are now back in MLS.

The 2025-26 season kicked off with two Americans on Premier League goalkeeping depth charts, although both appear to be third-choice. One, Gabriel Slonina of Chelsea, returned after two seasons on loan at Eupen and Barnsley. The other, England-born Brandon Austin of Tottenham, held his own in a one-off start. As the only homegrown player on Thomas Frank’s squad, he doubles as a crucial piece in Champions League squad registration.

The evolution of the goalkeeper position

One commonly cited reason for the sudden falloff of American goalkeepers is the modern era’s redefining of the role.

For decades, a goalkeeper was viewed as a specialist tasked with stopping shots and thumping the ball down route one. That all changed in 2016, the very same summer that saw Howard leave Everton. When Pep Guardiola controversially benched captain Joe Hart (a traditional keeper) for Claudio Bravo and then Ederson a year later, it changed perceptions of how the position should be played at the highest level.

An amendment to the IFAB’s Laws of the Game has expedited this trend. Since the 2019-20 season, goal kicks no longer need to leave the box before a teammate can receive it.

The adjustment enabled using short passes to start possession sequences. In 2016-17, according to Opta, Premier League keepers launched 76% of all goal kicks into the opponent’s half. In 2024-25, that rate had halved to just 38%. Suddenly, ball control and passing ability became key criteria for a goalkeeper.

“In terms of the build-up, at Liverpool, we worked really hard on trying to, as a team, beat the press of the opposition,” Robinson said. “With that is recognizing the state of the game, and recognizing that if their team is high pressing, there’s going to be space somewhere else. That might be behind the last line, that might be into the 10 position. It might be wide. You just have to recognize it.”

Hyde pushes back against the popular notion that American goalkeepers can’t do deft work with their feet. It’s just that they were seldom asked to do these tasks until roughly a decade ago.

“I think it’s too simplistic, I do,” Hyde said. “I would argue that at the time, Tim, Brad — both of them, even when Friedel was playing at Tottenham — they were still effective at what they were asked to do. You think about the initial sort of evolution (of the role), when you had to put the ball out to the fullback – they all were very proficient at doing that.”

The 21st century has also seen a rapid evolution of how clubs analyze transfer targets. In the past, many clubs leaned into observed archetypes if a nation was prolific at producing similar types of high-level players. The American goalkeeper was a shortcut akin to, say, targeting a Brazilian playmaker or an Italian defender.

The success of one or two players could open doors for the next handful of compatriots. These days, the financial ramifications of the sport’s highest level and the increased access to extensive data means clubs leave far less to taking a chance on stereotypes.

“There’s definitely an increase in the quality of scouting that’s going on out there,” Robinson said. “I think there’s a broader range of goalkeepers that have been brought up from all over the world. Essentially, I think clubs are getting smarter and smarter about how they (recruit).”

These evolutions aren’t cause for defeatism. It requires a modified approach to development – one that starts far from the spotlight. Hyde credited U.S. Soccer for hiring Robinson fresh from his time at Liverpool, bringing a modern Premier League-winning goalkeeper expert into the fold. As the head of goalkeeping, Robinson says he aims to “leave the Federation in a better place than when I found it.”

Jack Robinson (right) enjoyed success as one of Liverpool’s goalkeeping coaches before joining U.S. Soccer (Photo by Andrew Powell/Liverpool FC/Getty Images)What U.S. Soccer is doing about it

Robinson and his team are creating a goalkeeping ‘B’ coaching license and will subsequently launch a goalkeeping ‘A’ license. Another of Robinson’s aims is to create accessible instructions for all coaches, whether they’re a national team assistant or “the mums and dads who are coaching the kids on a weekend.” Given the country’s size and how sparsely the geography can be covered with pro academies, local youth clubs are a vital part of this all.

“We will make sure that the whole ecosystem gets an opportunity to have education on the goalkeeping side,” Robinson said, citing the importance of the grassroots programs. “That’s where the passion and the love for the role comes. We want to get young boys or girls to be passionate about goalkeeping, and that starts at your local club.”

When working at the FA, Robinson joked he could visit any club rostering a promising prospect with a two-hour drive from headquarters. A similar approach to scout the best talent in the U.S. would deplete the federation’s mileage budget.

U.S. Soccer is already trying to improve its outreach to all parts of the nation. Having split the U.S. into six geographic regions for youth talent ID camps, Robinson is working to launch goalkeeping-specific sessions as part of those three-times-a-year sessions. This would allow a greater number of young players to convene, also allowing interested youth goalkeeping coaches to come in and touch base with the players and federation alike.

Robinson won’t push a one-model-fits-all approach. Instead, adaptability and a bedrock of positional awareness is central to the positional profile for the next wave of American goalkeepers.

“What I would like to see as we’re developing our goalkeepers, from the younger ages through to the senior level, is that we have goalkeepers who can play in any team, any system, any formation, so that they have the ability to play if the opportunity is there,” Robinson said.

“I think the biggest things I want to see in the goalkeeper that we’re trying to develop in the youth side and going to the senior team is that they show emotional control, they’re adaptable, and able to play under pressure in different types of games against different styles and they’re impacting the game. I think those are the three things that are important for me as we go forward.”

Refining how goalkeepers are coached is something Howard sees as mandatory.

“There’s one train of thought that there was just something in the water in that generation and that we thrived – but the bigger part of it is goalkeeping coaching,” Howard said. “We still produce the athletes – we see it all the time – we produce the goalkeepers. But goalkeeper coaching on the whole in this country has gone downhill and I think goalkeepers are suffering the price for that.”

Tim Howard, right, alongside Clint Dempsey at the 2014 World Cup in Brazil. (Photo by Kevin C. Cox/Getty Images)There’s no substitute for match experience

Developing the positional awareness that Robinson is seeking requires one element that has been in short supply beyond the domestic leagues for Americans: game action.

“You can’t replicate the process for a goalkeeper of going through a game,” Hyde said, “in terms of: the prep before, going through the game, the warm-up, doing the game, and then the recovery and getting into the routine and the rhythm of reviewing and then working again, building up. It’s really, really important to be able to have the rhythm within all that.”

But only one goalkeeper starts per team, and prospects can’t enjoy the same gradual incorporation into a team that outfield players are afforded.

“The leash on a goalkeeper is always shorter,” Hyde said. “With an outfield player, you give him 20 minutes here and 10 minutes here. You’ve got a cup game, he’s playing for 90 minutes. Then we’ll train him for a little bit, and give him 30 minutes, 20 minutes, 20 minutes. Before you know it, he’s racked up a ton of minutes within a season, and then the next year, he’s starting games.

“You don’t throw a goalkeeper in for 20 minutes. You have to prime them to deal with the ups and downs and be consistent in doing the things that are expected of them. Because then, they’re strong enough then to deal with the downside of when they don’t perform well. They’re able to bounce back.”

The same predicament has played out for the USMNT since Pochettino took over last September. Ten goalkeepers have been named to his squads over the past 12 months. From the outside, it resembles a reality competition where a winner won’t be named until the last minute.

Nonetheless, Robinson backs the approach and is confident it’ll lead to the right option next summer.

“Now it’s down to them,” Robinson said. “They have to perform for their clubs. They have to be fit and in rhythm when it comes to the selection, because anything can happen in these nine months. We wanted to make sure that we saw as many of the goalkeepers we could. We understood them; we know what they’re like character wise. We’re monitoring them every single week, we’re watching all the games that are playing.”

May the best of MLS win?

Unlike the predecessors who fostered the U.S.’s goalkeeping reputation and plied their club trade abroad, the competition to start in goal at the 2026 World Cup is almost exclusively playing out in MLS stadiums. Turner is back from his European sojourn, starting again for the New England Revolution. Steffen has rediscovered his previous consistency since joining the Colorado Rapids last year. Matt Freese, whose penalty-stopping prowess made him a Gold Cup hero, starts for New York City FC.

Patrick Schulte started at the 2024 Olympics and is in his third season starting for a Columbus Crew side that fosters the highest rate of possession in MLS. Roman Celentano offers a more traditional shot-stopper for FC Cincinnati, while Chris Brady is already a surefire starter with the Chicago Fire at age 21.

Columbus’s Patrick Schulte makes a save for the USMNT vs. Canada (Photo by Jay Biggerstaff/Imagn Images)

“It’s an exciting time, really,” Hyde said. “These guys all want to compete, and this is where it’s at. They’ve got to get out there every week and get it done, then give Poch and (goalkeeper coach) Toni Jiménez a headache about who they’re going to pick. That’s what you want as a coach, rather than the necessity of ‘I have to play this guy.’”

Rather than repeat this contest every four years, the efforts to improve education and crystalize a positional profile are being done to dependably have options. Not just prospects, as Robinson is quick to emphasize, but viable alternatives to an incumbent starter to keep them fresh.

It’s hard work, readying someone to excel in the sport’s loneliest position. Still, it’s something that the U.S. once did as well, if not better, than every other nation. For a program aspiring to compete at World Cups, shoring up the last line of defense is mandatory.

That begins at an early age, in parks and backyards across the country.

“We want to try and make sure that if somebody does have a passion when they’ve put the gloves on for the first time, that we continue that passion,” Robinson said. “That comes through the way that you coach them and the relationships you build with them. It also comes from having role models. Hopefully in the summer, on the men’s side, there can be a role model for young goalkeepers, like we had with Brad Friedel and Tim Howard and Kasey Keller.

“But hopefully, it’s not just one. Hopefully, it’s a good production line of goalkeepers coming through who enjoy the position and take that challenge on board to be the best that they can be.”

(Top illustration: Kelsea Petersen/The Athletic; Richard Sellers/Getty; Kvork Djansezian/Getty; NurPhoto/Getty)