From the very beginning, those watching the Cleveland Indians (now the Guardians) play the New York Yankees that warm September afternoon in 1951 knew it was a classic, a game Joe Trimble of the New York Daily News called a “tummy-trembler from start to finish” and one of the “truly great games at” Yankee Stadium that year.

The Indians and the Yankees were fighting for first place in the American League, a mere three percentage points apart. Both had been either first or second since July 29, never separated by more than three games during that time. Both had only a handful of games remaining. Both were among the league leaders in earned-run average.

There was, however, one glaring difference that made this moment historic: The Indians were one of six baseball teams that were integrated; the Yankees were among the 10 teams that were not.

It was fitting that Cleveland would push the Yankees to the brink in 1951 just as integration was taking hold in baseball, if not the rest of the country. Without the Indians fielding Black players such as outfielder Larry Doby and first baseman Luke Easter, with their 47 home runs, the Yankees would have been comfortably ahead in the pennant race and the game in Yankee Stadium would have been just an ordinary late-season contest.

Instead, this game, as well as the 1951 season, was the beginning of the end for the Old Era of baseball: An all-white team playing against an early champion of integration. And it took place just one year after the Yankees beat the Philadelphia Phillies in what would be the last all-white World Series.

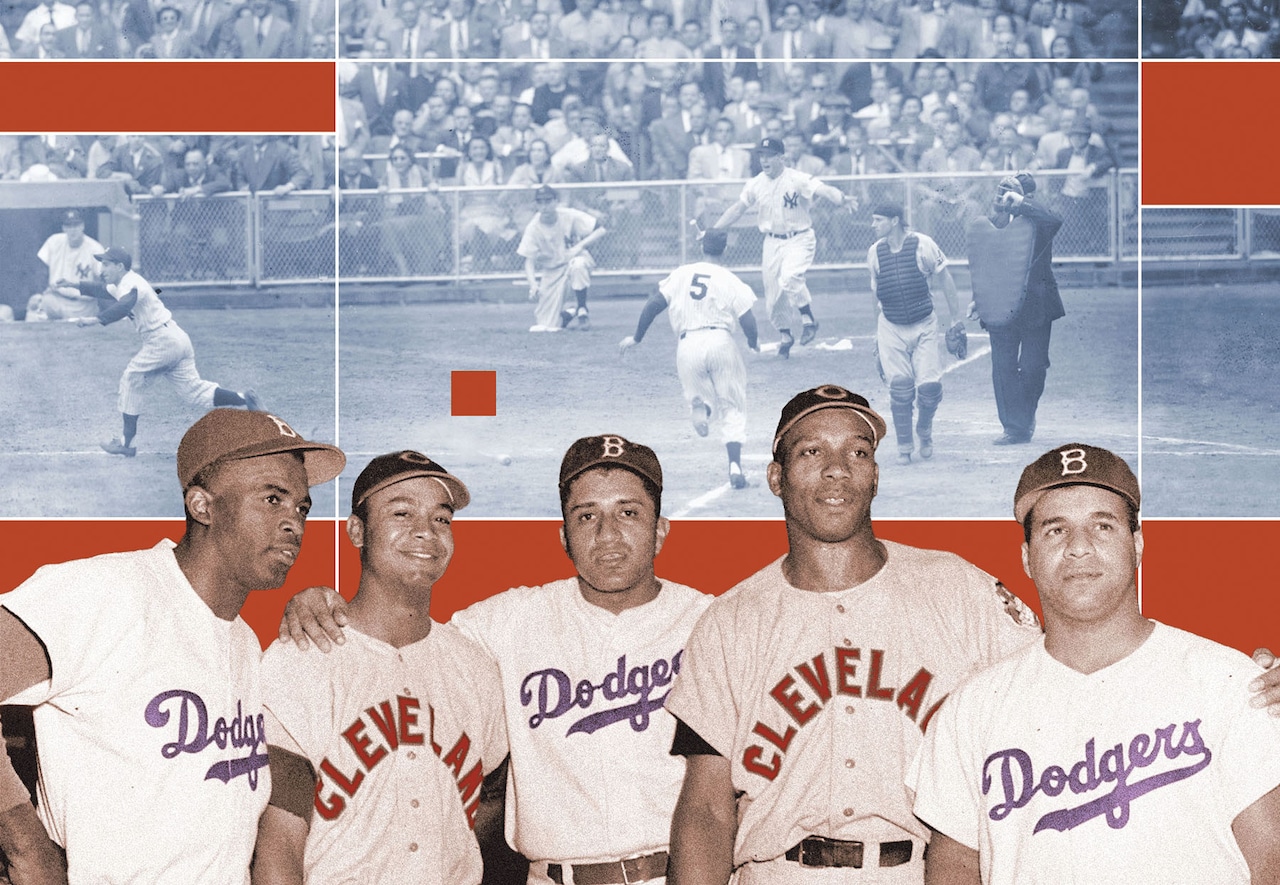

A Cleveland victory likely would set up the first World Series between two integrated teams – Cleveland against either the Brooklyn Dodgers or New York Giants – three teams with 13 of Major League Baseball’s 19 Black players. The Indians, Dodgers and Giants had turned in three of baseball’s best four records while all-white teams produced seven of baseball’s eight worst records

The Yankees’ 2-1 victory on shortstop Phil Rizzuto’s suicide squeeze bunt in the bottom of the ninth – an inning the Associated Press’ Jack Hand wrote had “all the drama of a World Series finale” – helped the Yankees win the pennant and postponed until 1954 a World Series between two integrated teams – Cleveland and the New York Giants. (The Giants won in four straight games.)

Despite the Indians losing that 1951 game, the success of the Indians, Giants and Dodgers, and the play of rookie Willie Mays of the Giants, shattered any illusions among baseball executives that teams other than the Yankees could win pennants without integrating.

Brooklyn Dodgers co-owner Branch Rickey’s audacious experiment in 1947 by signing second baseman Jackie Robinson, followed shortly after by Indians owner Bill Veeck purchasing the contract of Doby from the Negro Leagues, did not open the floodgates to wash away Major League Baseball’s long and all-but-official policy of racism and exclusion.

It was a trickle until 1951, when 19 Blacks appeared in the major leagues compared to only nine in 1950.

“Where would Brooklyn be without” Robinson, catcher Roy Campanella and 20-game winner Don Newcombe, the influential Wendell Smith wrote in the New Pittsburgh Courier in September 1951. “Where would the New York Giants be without” outfielder Monte Irvin and Mays, who “many believe will one day be the greatest of them all? Where would the Cleveland Indians be” without Doby and Easter?

The Indians-Yankees game on Sept. 17, 1951, was played against the backdrop of seething racial tensions across the nation. Just two months earlier, Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson dispatched 500 National Guard troops to the Chicago suburb of Cicero to suppress a riot by more than 3,000 whites who opposed a Black family moving into an all-white apartment building.

One week after the game, more than 200 pounds of dynamite ripped through a Florida apartment complex which Black families were expected to soon occupy. A few months later, Harry Moore, executive secretary for the Florida NAACP, and his wife Harriette, were murdered on Christmas night when a bomb planted by the Ku Klux Klan ravaged their home in the Florida town of Mims.

Yet the integration of the Indians, Dodgers and Giants was more than simple racial justice. The three teams – welcoming great players from the Negro Leagues — wanted to win the World Series, and that meant beating the omnipotent Yankees, who had won nine World Series titles since 1936.

Just months after the 1951 season, outfielders Henry Aaron and Wes Covington signed with the Boston Braves, a team that already was integrated. In 1953, the Cubs purchased the contract of shortstop Ernie Banks from the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues, and the Cincinnati Reds signed outfielder Frank Robinson out of Oakland.

In the aftermath of 1951, the number of Black players in the major leagues increased to 37 in 1954 — and by 1959, every team was integrated. The Philadelphia Phillies, Boston Red Sox and Detroit Tigers, among baseball’s best teams in 1950, were the final holdouts and paid dearly for that reluctance as they slid toward mediocrity.

Jack Torry covering the 2016 Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia. (Photo courtesy of Jack Torry)

Jack Torry covering the 2016 Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia. (Photo courtesy of Jack Torry)

Yet even the Indians were slow to deal with the racism encountered by their four Black players. As late as 1951, the Chase in St. Louis and Del Prado in Chicago would not accept Blacks as guests at their hotels. That led Cleveland General Manager Hank Greenberg to belatedly announce in November that the team would leave the Del Prado for the Hotel Sherry.

Oh yes, there was one more dramatic change in 1951. That year, the first African Americans to play Little League baseball in the South joined a team in Norton, a small town in southwest Virginia.

Jack Torry is the former Washington bureau chief for the Columbus Dispatch and Dayton Daily News.

Have something to say about this topic?

* Send a letter to the editor, which will be considered for print publication.

* Email general questions about our editorial board or comments or corrections on this opinion column to Elizabeth Sullivan, director of opinion, at esullivan@cleveland.com

If you purchase a product or register for an account through a link on our site, we may receive compensation. By using this site, you consent to our User Agreement and agree that your clicks, interactions, and personal information may be collected, recorded, and/or stored by us and social media and other third-party partners in accordance with our Privacy Policy.