SEATTLE, Wash. — The death of an orca calf this weekend has renewed questions about the health of the Southern Resident population and what other factors are at play.

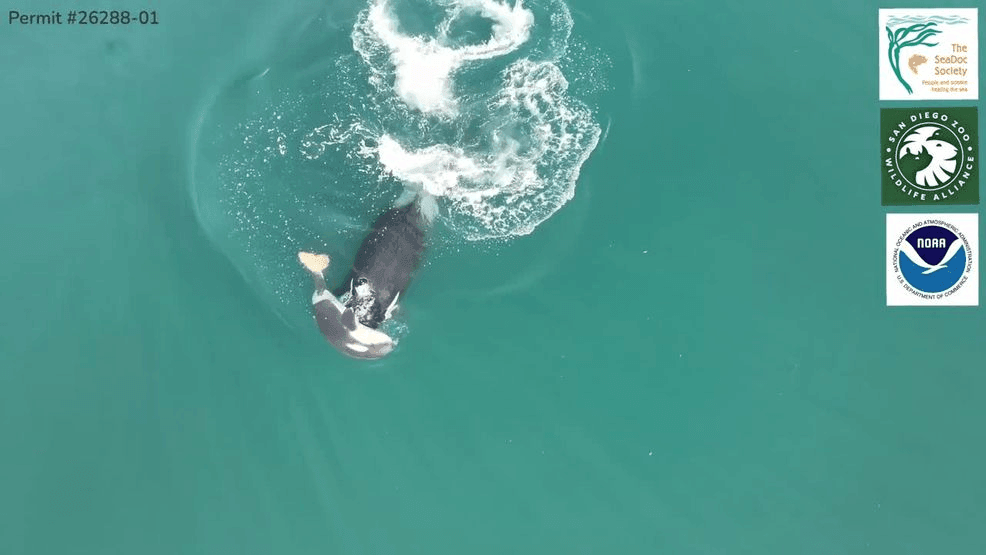

On Saturday, the SeaDoc Society and Center for Whale Research reported that J-36 was spotted carrying her dead newborn calf in the waters of Rosario Strait. SeaDoc reported that she was approximately four miles behind a larger group of J-pod animals moving south and east of Orcas Island.

PREVIOUS COVERAGE | Southern Resident orca seen carrying dead calf near San Juans in possible grief display

It is another discouraging development for those who track the endangered species, which is synonymous with the region.

“They could see her just under the water, carrying that baby over her nose. It was heartbreaking,” said Joe Gaydos, the Science Director for the SeaDoc Society.

Another J pod orca, J35 Tahlequah, previously garnered national attention after she was seen carrying her dead calf for 17 days in 2018, pushing its body for over 1,000 miles through Pacific Northwest waters. J35 lost another calf in 2025 and repeated the process, carrying the body for over 10 days.

Researchers believe this behavior is a sign of grieving among orcas, and it has sparked dialogue over the emotional complexity of animals.

“The parts of their brains that are responsible for things like memory, emotions, and language are very well developed, in fact, in some ways more developed than the human brain,” said researchers from Wild Orca.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if the grieving process doesn’t last a lifetime like it does with humans when a baby is lost,” the researchers added.

And, unfortunately, the Southern Residents experience quite a bit of loss.

“There’s a high mortality rate in pregnancy, almost 70% of the females in this population (are) losing their calves,” said Dr. Deborah Giles, who is a killer whale scientist and was on the scene when the discovery was made. Speaking from an office on Orcas Island, she added, “There’s a lot of different threats facing this population of whales, but I think the general consensus is that it’s a limited prey abundance and quality that’s the biggest issue, the lack of high-quality and high-density Chinook salmon.”

“A loss like this is devastating. A young female calf of a mom who’s not represented yet in the population,” added Dr. Hendrik Nollens, the Vice President of Wildlife Health for the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

The Southern Resident Orca population was decimated in the 1960s and 1970s, with roundups and relocation to aquariums. By the early 2000s, the endangered population was believed to have stabilized around 100, but has dropped to 74 now.

“As Bill Clinton said, it’s the economy, stupid. Right now, what we need to remember is that it’s the ecosystem, stupid,” said Fred Felleman, a Port of Seattle Commissioner who first moved to the region to study the species.

He was visibly angered by the loss of the calf.

“You can go to a gift shop, you can adopt an individual whale, but I’ve yet to see a gift shop that sells ecosystems,” he said. “We know salmon are essential to their existence, and Chinook salmon in particular. But salmon need cold, clear rivers that have tree cover and things like that.”

RELATED | Southern Resident orcas face uncertain future despite groundbreaking research efforts

Nollens added that a loss such as this one is also tough to deal with because gestation is 17 1/2 months, and its recovery is not a quick process.

“They have the capacity to live into their 80s or older for females, into their 60s or older for males, but we’re losing males in their late 20s, and we’re losing females in their late 30s and into their early 40s. That end of the population is a concern as well,” said Giles, who also noted that there should be six births a year and only two of the four born in the wild have survived this year.

“We need these animals to have babies. Need them to have females. We need them to grow up, get pregnant, and continue to do that; that’s the way you have a healthy population. I think what we saw was her carrying her baby around. It’s like they’re having the same sort of emotional thing that we would have if we lost a child at birth,” said Gaydos.

He said experts in the field need to figure out why calves have so many issues.

“That’s on us, to bring back salmon, to reduce vessel noise, and to see if there’s any sort of thing, like an infectious disease or something else that could be contributing to this that we can help out with. For us to see that, it just reminded us that we have a lot of work to do,” said Gaydos.