In the middle of a worldwide water crisis, scientists from MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) are working on an innovative technology: devices capable of extracting potable water directly from the air, even in the driest places. I know this might sound so strange, but this project has already been tested in Death Valley, which is one of the driest and hottest places on Earth, and it showed very promising results. So, let’s find out more about this MIT project.

How this MIT technology works

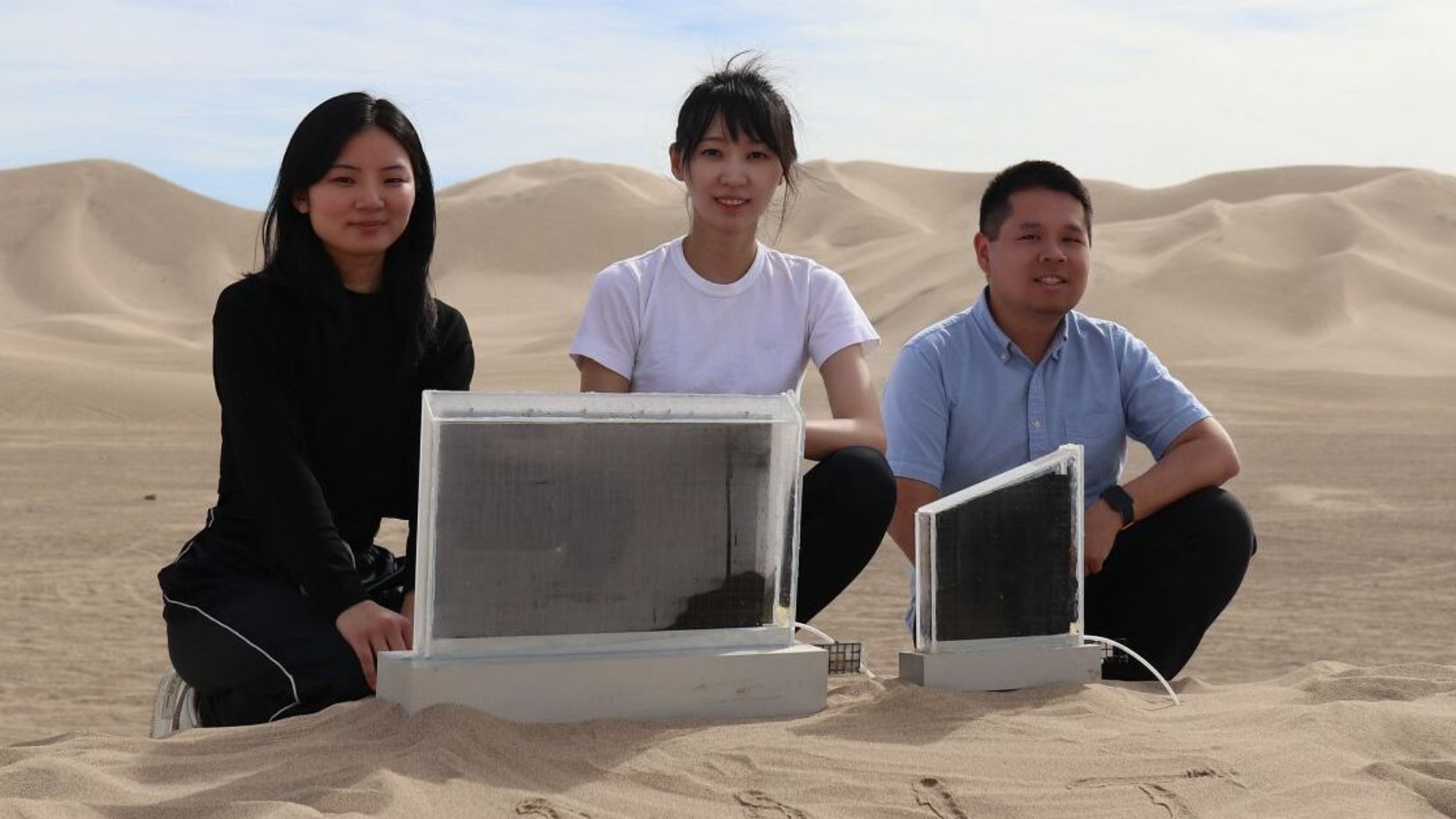

The team from MIT designed a device with the size of a window made of hidrogel, which is infused with salt, folded like origami, and sealed in glass. But, how does it work? Hydrogel seems like a kind of black plastic with bubbles, and it absorbs water vapor from the air. Then, when the sun heats the panel, hydrogel releases humidity and the water condenses on the glass and flows through the tube, transforming it into potable water ready to drink.

However, the most remarkable aspect is that the system doesn’t need electricity, just natural heat from the sun.

How much water does it produce?

Currently, MIT technology generates about two-thirds of a cup of water under extremely dry conditions. Even though it’s not a lot, the final goal is that it can supply enough potable water for an entire home, even in deserts.

Lack of water as a global challenge

More than 2 billion people around the world don’t have access to safe potable water since climate change is worsening issues like longer droughts, shrinking reservoirs, and increasingly erratic rainy seasons. This is why making the most of the humidity from the air seems to be an attractive alternative. It’s true the technique of collecting water from fog is not new, but the challenge was to do it in dry environments where the air contains very little humidity. That’s where MIT innovation plays a crucial role.

Hydrogels role

Hydrogels are the heart of this technology, they are spongy materials (similar to those used in diapers) capable of absorbing up to 10 times their volume in water even in dry climates.

According to Evelyn Wang, from MIT, hydrogels are cheap and require little energy to release the absorbed water. These features make them particularly promising for atmospheric water harvesting.

Recent projects with hydrogels

Interest in hydrogels has increased worldwide. Let’s take a look at more examples of experiments using hydrogels:

A project in the Atacama desert, the driest nonpolar place on Earth, produced 0.1 gallons of water per square meter per day with a mix of hydrogel and salt.

Another experiment in Las Vegas developed a hydrogel membrane inspired by three frogs and air plants that can yield one gallon of water per day.

Critics and limitations

Despite the enthusiasm, MIT technology faces important challenges like:

Low production: the amount of water obtained is still limited.

High cost: producing water with this technique costs around 10 times more than tap water and more than desalination. Yet, it’s cheaper than bottled water which could justify its use in specific situations.

Experts point out that its most realistic applications will be, at the beginning, in industries that need ultrapure water, such as semiconductors, batteries, or medical equipment. What’s more, it could also be used in emergencies like hurricanes or in military operations.

A promising future?

Some critics think atmospheric water harvesting is a distraction, but the global market already exceeds $2 billion and is growing. Companies in Israel and the U.S. are developing commercial systems capable of producing hundreds of gallons of water daily.

Paul Westerhoff, a professor at Arizona State University, predicts a commercial “boom” within the next decade as costs drop and production scales up.

So, with continued advances from MIT and other research groups, turning air into water could move from scientific curiosity to an essential tool in tackling worldwide water scarcity.