The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit will hold a key hearing on Tuesday regarding how many years Division I players should be eligible to play.

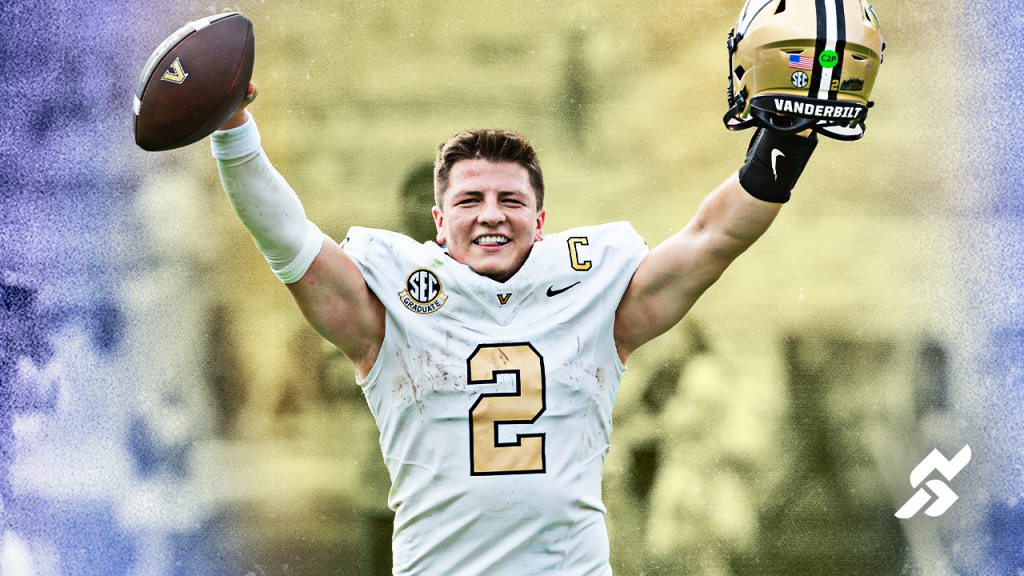

The hearing specifically concerns the NCAA’s appeal of Chief U.S. District Judge William L. Campbell Jr.’s ruling last December to grant Vanderbilt quarterback and former JUCO transfer Diego Pavia a preliminary injunction to play this fall.

Pavia, 24, is now in his sixth college season; he played his first two seasons at JUCO New Mexico Military Institute and last four at New Mexico State and Vanderbilt. The NCAA limits eligibility to four seasons of intercollegiate competition—including JUCO and D-II competition—within a five-year period.

Through antitrust law, Pavia has thus far successfully challenged the application of NCAA eligibility rules to his eligibility. He contends the NCAA and its member schools and conferences, which are competing businesses, have unlawfully conspired to limit how long a college athlete can sell their football services to a school that wishes to place them on its roster.

Campbell agreed, reasoning that Pavia is part of a labor market of D-I football players who participate in an increasingly professionalized college sports environment. Those players market their services to universities, vie for NIL deals and, in the wake of U.S. District Judge Claudia Wilken approving the House settlement, pursue cuts of revenue shares. Campbell found that the NCAA and its members agreeing to limit eligibility for former JUCO players, and thus those players’ opportunities to earn money, is legally problematic.

To that point, there is real money to be made for college football stars nowadays, which in turn incentives them—especially if they’re not NFL prospects—to prolong their status as NCAA athletes for as long as possible. The reality is that many college stars won’t make it as pros; fewer than 2% of college athletes become pro athletes. Given that universities have numerous graduate programs, a player could stick around for a long time as a “student.”

Pavia is a good example of a player who might want to remain a college athlete for as long as he can. Listed at 6-foot, Pavia would be relatively short for an NFL quarterback, who, USA Today has estimated, has an average height of 6-foot-3. But he has excelled for the Commodores and, now in his mid-20s, might be in his peak athletic years. Pavia is also knowledgeable at reading college defenses and has acquired other skills that come along with game experience. In June, Pavia revealed his market as a D-I football player: He said he was offered $4-$4.5 million by other colleges to transfer.

Pavia’s injunction has spawned lawsuits by more than 30 similarly “seasoned” college athletes who seek the chance to keep playing. The NCAA has thus far defeated most of those lawsuits, with some judges reasoning that NCAA eligibility rules, which concern how long a college student can play a sport, aren’t subject to antitrust scrutiny, which concerns commercial dealings. Other judges have found antitrust scrutiny applies, but that the eligibility rules comply with antitrust law. And still other judges, like Campbell, see the rules as unlawfully restraining a labor market in certain instances.

With conflicting court rulings, there is the prospect of a “circuit split,” which refers to when federal circuits reach conflicting conclusions of law about the same topic—an outcome that sometimes draws the interest of the U.S. Supreme Court. In July, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit sided with the NCAA against a case brought by Wisconsin cornerback Nyzier Fourqurean. If the Sixth Circuit sides with Pavia, college athletes and their schools in different federal circuits effectively have different rights absent the Supreme Court intervening.

In preparation for next Tuesday’s oral argument, attorneys for the NCAA and Pavia recently answered the Sixth Circuit’s request to explain two topics: 1. Whether the House settlement impacts how antitrust law should regard NCAA eligibility rules and 2. Whether Pavia’s case is moot since after Pavia obtained an injunction, the NCAA granted him and similarly situated athletes a one-time waiver for the 2025-26 academic year.

The NCAA’s brief—authored by Taylor J. Askew, Rakesh Kilaru and other attorneys from Holland & Knight and Wilkinson Stekloff—argues that the House settlement “only strengthens the case for reversal.”

As the NCAA tells it, the House settlement reaffirms the five-year rule. The settlement contains language that authorizes the NCAA to adopt or affirm rules “governing the number of seasons” and “length of time student-athletes are eligible to receive benefits,” including settlement compensation.

The NCAA also quotes an amicus brief filed by the American Council on Education, which opines that matching eligibility to play a sport to the normal four-year path to a college degree “prevents intercollegiate athletics from becoming an indefinite detour from—rather than a complement to—education.” Along those lines, the NCAA maintains this limitation envisions college students who play sports entering the real world alongside their classmates, with roster spots then opening for rising freshmen. Further, the five-year rule arguably helps to distinguish college sports, which feature full-time students playing on teams, from pro sports, where players play for as long as they and a willing team employer agree they play for some amount of money.

The NCAA also asserts that its appeal isn’t moot on account of the waiver, which the NCAA pledges it won’t revoke if the Sixth Circuit reverses Campbell. The NCAA contends the Pavia case still presents a live controversy since Pavia “has kept open” the possibility of pursuing “additional seasons” beyond 2025-26. Pavia, at least in theory, might try to remain the Commodores starting quarterback for years, during which he could earn many millions of dollars in NIL and revenue-share money. Quarterbacks can play well into their 30s, even 40s.

Further, the NCAA says its appeal is necessary because Pavia’s case has “incited a wave of similar lawsuits in courts across the country.” These cases, the NCAA writes, “are often brought in an emergency posture”—with the player seeking an urgent response by a judge to let them play before their college gives their spot to another player. The NCAA argues a “seemingly endless wave of litigation is profoundly destabilizing for college sports,” a position President Donald Trump enunciated in his recent executive order on college sports.

Pavia’s attorneys, Salvador M. Hernandez and Ryan Downton, offered a very different take in their brief. They depict the House settlement as enlarging the professional aspects of college sports. Put bluntly, colleges will now pay players directly tied to them playing sports.

To that end, the House settlement calls for schools to be able to share up to 22% of money from media rights, ticket sales and sponsorships to athletes. The cap for 2025-26 is $20.5 million and is expected to increase to $32 million over the next decade. Pending potential Title IX challenges, football players will probably receive up to 75% of the revenue share, which Pavia points out means “approximately $15 million per year at Power Four Conference schools.”

This House settlement framework, Pavia insists, further transforms D-I football, especially at the power conference level, into a professional market.

“To the extent the NCAA ever had a valid argument that its eligibility rules were not commercial because they only indirectly determined who could receive NIL compensation, and Mr. Pavia maintains they did not, that argument no longer exists after House; now, NCAA eligibility rules directly determine who receives revenue-sharing compensation from NCAA member schools,” Pavia’s brief charges.

Pavia agrees with the NCAA that the association’s waiver doesn’t moot the appeal. But Pavia’s reasoning is different. His brief says the case is not just about JUCO transfers but more broadly “the anti-competitive effects of the NCAA’s application of the so-called redshirt rules.” Pavia’s attorneys recently filed a separate lawsuit, Patterson v. NCAA, that takes aim at redshirt rules and argues college athletes should have five years to play when they have five years to practice and five years to graduate.

A three-judge panel will hear each side deliver their oral argument, with each allotted 15 minutes. The three Sixth Circuit judges are Amul Thapar, Chad Readler and Whitney Hermandorfer. All three, like Campbell, were appointed by Trump. There is no set time on when the three judges will issue their decision, but it will likely be made during the next few months.