As the Léon Thévenin eased into Cape Town port last month, Shuru Arendse was ready to rush home to his family. He had a month off and a laundry list of to-do’s: fix a leaky tap, patch a hole in the roof, take his two children to the trampoline park.

But halfway through Arendse’s leave, there was a phone call: An undersea internet cable off Angola was malfunctioning. The Thévenin, the only cable repair ship permanently stationed in Africa, was heading off to fix it, and Arendse was needed. He is a cable jointer — one of a handful of people on the continent who know how to splice cables together.

Shuru Arendse, cable jointer, receives a hug from seaman Didier Towanou.

His wife got angry. “Shuru, we didn’t even get a chance to do anything yet,” he recalled her saying.

The ship has taken Arendse all along the African coast and given him a sense of purpose. But it has been at the expense of his family, the 43-year-old said. Cable-ship crew like him can spend weeks to months at sea, interspersed with periods of shore leave.

“I’m an absent parent,” he told Rest of World. “Because of that guilt, I spoil my children. What I do is, I buy, buy, buy.”

Working on an internet cable repair ship is grueling but rewarding — and never more important than in today’s hyperconnected world, a handful of the Thévenin’s crew members told Rest of World. This report is based on three years of observations and two weeks onboard the ship.

The Léon Thévenin anchored near Réunion.

“I’m trying to save a country from losing its data or communication,” Arendse said. “I love the challenge of it; it’s never the same.”

Data races from people’s devices over terrestrial networks to exchange points and data centers, where it is routed and sometimes sent abroad through massive undersea internet cables. Some of these stretch thousands of kilometers across ocean floors before surfacing at distant cable-landing stations and rejoining land-based internet.

With the artificial intelligence boom, the infrastructure through which data travels has taken on more importance, Steve Song, senior director of infrastructure mapping at the nonprofit Internet Society, told Rest of World.

“There is no AI without high-speed connectivity,” he said. “There’s every reason to believe that demand [for cable capacity] will continue to go up, mostly thanks to streaming media, and now perhaps due to … AI.”

Most of the world’s data is managed by big tech firms including Alphabet, Meta, and Amazon, which consumed 3.6 billion megabits per second of bandwidth in 2023, according to the research firm Telegeography. That’s roughly as much data as 700 million people streaming Netflix at the same time. The companies operate global content distribution networks, which rely on undersea cables to move data quickly around the world.

Kevin Willenberg (left), able seaman, and officer Charles Khumbuza support operations on the main vessel from a small boat alongside it.

Kevin Willenberg (left), able seaman, and officer Charles Khumbuza support operations on the main vessel from a small boat alongside it.

Eugene Boonzaier (left) works on the protective casing around a recently completed repair. The cable will then be returned to the ocean.

Eugene Boonzaier (left) works on the protective casing around a recently completed repair. The cable will then be returned to the ocean.

Kilometers of spare cables are stored in large cable tanks for use in repairs.

Kilometers of spare cables are stored in large cable tanks for use in repairs.

The deck crew guides the cable out over a large wheel, called a bow sheave, returning it to the sea.

The deck crew guides the cable out over a large wheel, called a bow sheave, returning it to the sea.

In Africa, the companies used cables that were majority-owned by telecom providers until around 2022. Then, they moved in. China’s HMN Tech, formerly owned by Huawei, landed the Peace Cable in Kenya in 2022. Alphabet’s Equiano went live the same year. Meta’s 2Africa, the world’s longest cable at 45,000 kilometers (around 2,800 miles), will be operational later this year.

A cable lasts 25 years on average and requires upkeep. When an underwater storm or an errant anchor snaps a cable, the internet slows or cuts off somewhere on land. Repairing it becomes a matter of urgency.

The owners of the cable — usually a consortium of telecoms or big tech companies — pool resources to hire a cable-ship like the Thévenin. Depending on its age and condition, keeping a vessel at sea could cost $70,000 to $120,000 per day, according to Orange Marine, a telecommunications company based in France, which owns the Thévenin. There are 62 cable repair ships globally that remain on call at all times.

“We impact the lives of millions of people,” Didier Dillard, Orange Marine’s chief executive officer, told Rest of World. “We sail when we are required to sail, and we need to be ready to do it at any time.”

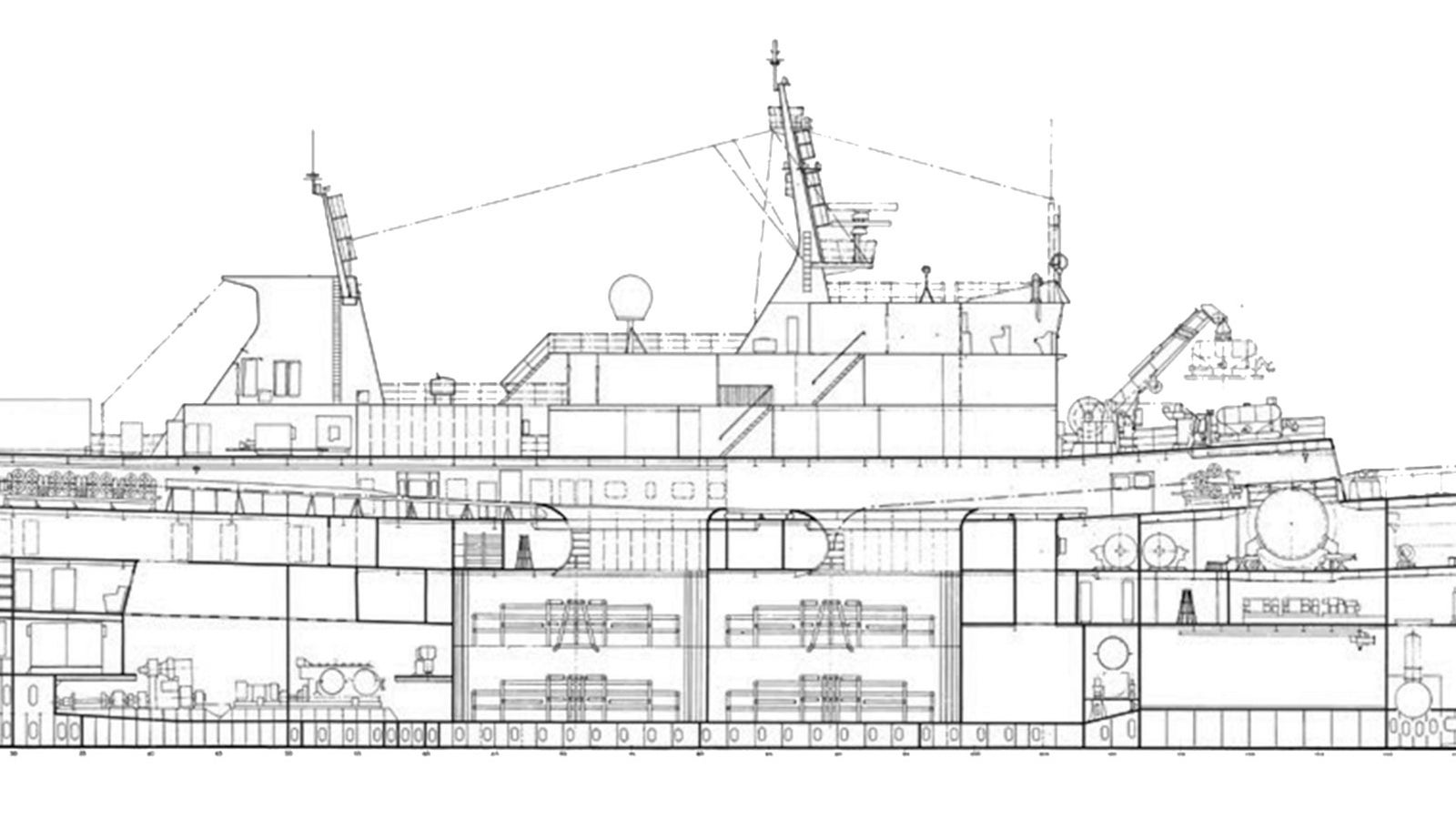

The Léon Thévenin is among the world’s oldest repair vessels. As long as a football field, rising three stories above the waterline, it is crewed by up to 60 people.

In June, South Africans noticed their internet slowing. The culprit was the West Africa Cable System, a 14,500-kilometer (9,000 miles) line that links Portugal to Africa’s west coast. Off Namibia, a junction box where three cables meet had failed and needed replacing. The Thévenin, which is responsible for repairs from Madagascar to Ghana, was called in.

“This type of repair is very special, because normally you do not find this kind of failure,” Benjamin Smith, the deputy chief of missions who coordinated the repair, told Rest of World.

The crew had to liaise with people in four countries, Smith recalled from his home in Cape Town. Back on shore leave, he said he was rarely without his toddler son, who nestled on his lap during the interview.

60

The number of times undersea internet cables could encircle the globe by 2040, according to projections.

At 43 years, the Thévenin is among the world’s oldest repair vessels. As long as a football field, rising three stories above the waterline, it is crewed by up to 60 people, mostly Africans. “It’s like a little floating city,” Thomas Quehec from France, the captain on rotation in July, told Rest of World.

Every corner of the ship serves a clear purpose. There’s a laundry room, bicycle racks, a dining hall, and a remotely operated submersible. But what sets cable ships apart are giant cable tanks that descend into the belly of the ship. They can hold thousands of kilometers of heavy fiber-optic cables, which are carefully coiled into place manually by crew members working in sync with machines.

The Thévenin has never been busier, Michel Senechal, director of submarine operations for Orange Marine, told Rest of World. The Congo Canyon, a deep valley slicing the Atlantic seabed and stretching 280 kilometers (174 miles) out to sea, has been suffering from an unusual number of underwater landslides. There has been an increase in cable breaks in the canyon, Senechal said, and the ship has more cables to maintain than ever before — now reaching 60,000 kilometers (over 37,000 miles).

The Léon Thévenin is like a small city that runs on trust and strong bonds between the crew. (L to R) Some crew members; morning tea break; the crew catch 40-kilogram tuna fish on a handline.

Two years ago, the ship was stationed close to the coast of Ghana, repairing a break in the West Africa Cable System. The equatorial sun was unforgiving. The workers, all men, sweated under thick protective gear and rubber boots. The vessel rocked and swayed as they used a special grappling hook to snag a cable from the depths.

The remotely operated vehicle, which resembles a giant dung beetle, is deployed sometimes to snatch up cables, but it was not needed this time. On deck, the crew hauled in the cable, leaving plenty of slack. If there’s too much tension, it would snap like a stretched elastic when cut.

Arendse, the cable jointer, described the steps of cable repair to Rest of World in July. The mission team contacts the landing stations to cut the power supply to the cable. At this point, everything goes quiet, he said.

Arendse works in a team of four to repair the damaged segment. This is a high-stakes, precise job that can take up to a day. “You can’t work alone, it’s too risky,” he said.

The workers seal the intact end, attach it to a buoy, and drop it into the sea. They then strip the broken section, exposing delicate hair-thin glass fibers, which they fuse with fresh cable. A speck of dust or even a tiny misalignment would ruin the joint and they would have to start over.

“Our job is very intricate, and we are not allowed to make mistakes,” Arendse said.

The Ghana repair lasted more than 48 hours. Typically, the crew pull 12-hour shifts daily, sometimes for weeks until the cable is repaired, captain Quehec said. Every worker is crucial to the effort, he said, especially the catering staff, who serve three hot meals a day for the hungry men.

Once a cable repair ends, the crew celebrate with a braai (barbecue in Afrikaans) as the ship heads back to its home port, Cape Town.

After a decade or more together, the crew feel like family, Trenley Padiachy, a bosun from Mitchells Plain in Cape Town, told Rest of World.

“We call it the ‘Love Boat,’” he said. “We spend more time with each other than with our own families, so we have formed strong bonds. We look out for one another.”

The ache of separation from family eased somewhat last year when the ship got a Starlink connection and Wi-Fi, letting sailors call and message home at any time. Before that, the ship only had a satellite phone, and the crew used shared computers with limited bandwidth, enough only for basic messaging.

The upgrade is a reminder of the benefits of being connected to the internet — and the stakes if a repair ship like the Léon Thévenin can’t fix a cable. The mission keeps the crew going, Didier of Orange Marine said.

“It’s hard to think of many professions where your work can affect so many lives so directly,” he said. “We are proud of that responsibility, and we take it very seriously.”