In May 2024, researchers at Georgetown Law’s Center on Privacy & Technology released a sprawling report on how the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) had quietly built one of the most expansive DNA surveillance systems in American history.

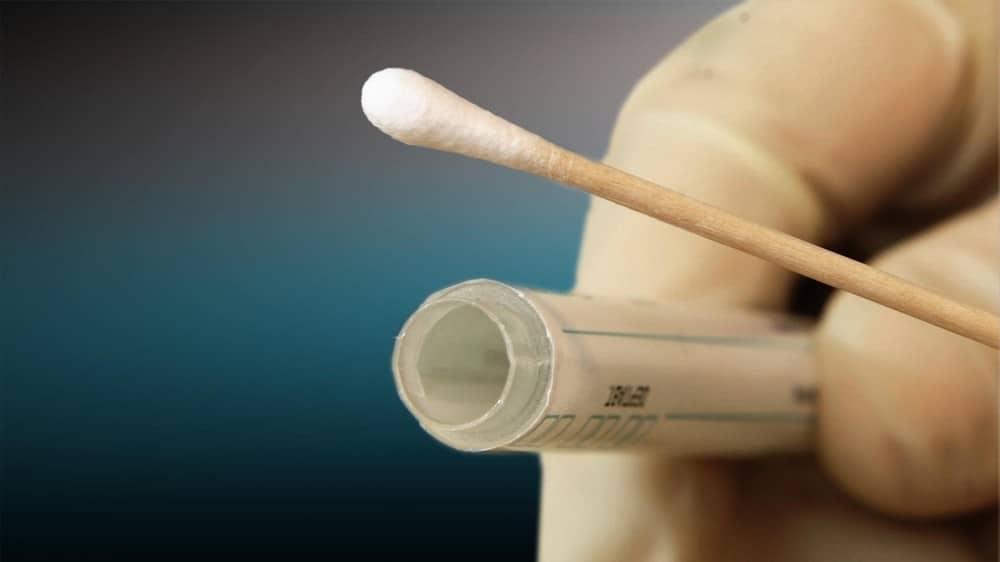

What began as a rule change in the waning days of Donald Trump’s first administration had by then spiraled into a massive dragnet. More than 1.5 million genetic profiles were funneled into the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) in just four years, dwarfing the pace of criminal law enforcement collection.

The report warned that immigration powers were being twisted into a tool for population-scale genetic monitoring, with people of color disproportionately swept up into the system.

The rule change by the Department of Justice implemented the Attorney General’s authority provided by the bipartisan DNA Fingerprint Act of 2005 to authorize DHS to collect DNA samples from certain non-U.S. persons it detains. The Biden administration though declined to fully implement the twenty-year-old law. In January, Trump mandated that the rule finally be codified into law in his Securing Our Borders Executive Order.

An update to the Center on Privacy & Technology’s original 2024 report confirmed that the worst fears were not only justified, they were grossly understated. Under Trump’s second administration, DHS and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) accelerated DNA collection, integrated a data infrastructure provided by Palantir, and pushed genetic surveillance further into the country’s interior.

Earlier this month, the Center on Privacy & Technology disclosed in an issue brief that between 2020 and 2024, CBP knowingly and repeatedly took DNA from approximately 2,000 U.S. citizens, including at least 95 minors, and sent those samples for inclusion in CODIS.

One 15-year-old in Laredo, Texas was swabbed after a minor drug accusation that prosecutors later declined to pursue. Others were adults pulled aside at airports or border crossings, with no charges ever filed.

In more than 500 cases, CBP listed the justification for swabbing U.S. citizens as “detainee,” although CBP Directive 3410-001A states that “CBP agents/officers may never document U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents as ‘detainees.’”

Together, the Center on Privacy & Technology’s reports paint a disturbing portrait of a government genetic collection program that is vast, legally dubious, and resistant to oversight. What began as a targeted measure aimed at noncitizens has spilled over to touch citizens, children, and communities far from the southern border, raising stark constitutional questions about privacy, due process, and the limits of executive power.

“The data also shows that DHS is taking citizen DNA knowingly and, in some cases, without stating any reason for doing so … The revelation that DHS regularly and knowingly takes DNA from U.S. citizens suggests new layers of potential illegality to a program that was already a flagrant abuse of power,” states the July updated report.

The software infrastructure used to stitch together genetic profiles with other biometric and personal data collected by the federal government is provided through lucrative contracts awarded by the Trump administration to Palantir, a company specializing in surveillance technology that has intimate ties to the White House.

Civil liberties advocates warn that this Orwellian infrastructure could evolve into a universal database that links DNA to individuals’ movements, communications, and family ties.

“Regardless of the citizenship status of the people from whom DHS takes DNA, this program must be understood as a leap toward universal genetic surveillance in the guise of immigration enforcement,” the Georgetown researchers declared. “It will not be possible to cure the injustices of the program by treating its impact on citizens as separate from its impact on everyone else.”

Biometric Update reported almost seven years ago that the FBI and other U.S. law enforcement and intelligence agencies were using “bio-forensic” DNA data to test whether genetic material can be parsed deeply enough to identify or narrow down unknown subjects of interest.

Comparing an unknown DNA genetic sequence against a known sequence may not create a one-to-one match, but if sufficient human DNA is sequenced at specific marker locations, a DNA profile for the unknown sample could be generated and then used to identify a relationship to known DNA profiles, especially the profiles of persons whose DNA has been recovered from crime scenes – or from anywhere.

“Noncitizens are most at risk because of DHS’s activities, but this program affects everyone,” the Center on Privacy & Technology said, pointing out that “DNA samples can reveal information not just about an individual’s most intimate personal details such as their biological sex, ancestry, health, and predisposition to disease, but also their biological relations today and across generations.”

Since 2020, CBP has ramped up its biometric surveillance capabilities by dramatically expanding DNA collection at the border, including the collection of DNA of children as young as four years old, Biometric Update reported in June. This despite CBP having assured in 2020, and again in September 2022, that only DNA from persons ages 14 to 79 is being collected.

When the Department of Justice eliminated the regulatory exemption that had spared DHS from full DNA collection, the consequences were immediate. In just four years, DHS added more than 1.5 million profiles to CODIS. By December 2024, the detainee index had swelled to 2.35 million, overshooting projections by nearly 95,000.

By spring 2025, another quarter-million was added, pushing the total past 2.6 million. DHS alone, with a fraction of the manpower of local police forces, was matching the DNA collection pace of the entire criminal justice system.

Records show instances where DNA was taken under statutes that were not criminal at all. In about 40 cases, CBP agents provided no statutory justification whatsoever, yet the samples were still forwarded to the FBI. For the individuals involved, there was no judicial oversight, no opportunity to contest the swab, and no path to expungement.

The legal stakes are clear. Federal law allows DNA collection from people arrested, charged, or convicted of crimes, and from noncitizens detained under federal authority. But nothing authorizes DHS to collect DNA from citizens absent criminal process. By doing so, the agency has exceeded its statutory limits and crossed constitutional boundaries.

Even the Supreme Court’s narrow ruling in Maryland v. King which permits police to swab individuals arrested for serious crimes with probable cause does not cover immigration detentions. Immigration “probable cause” is not subject to judicial review, and detention can be imposed on individuals who have committed no crime at all.

As Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in her September 2025 dissent in Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo, the court’s deference to mass detentions effectively authorizes the government to “seize anyone who looks Latino, speaks Spanish, and appears to work a low wage job.” Layered on top of DNA collection, that deference opens the door to population-scale genetic monitoring.

The Center on Privacy & Technology July update paints a disturbing portrait of who is being swabbed. Records obtained pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) show CBP sent DNA from tens of thousands of minors to the FBI. The oldest person recorded was 93. For minors, fewer than two percent faced any criminal charge, yet their genetic profiles are now permanently indexed as if they were offenders.

The vast majority of those affected came from just four countries – Mexico, Venezuela, Cuba, and Haiti – accounting for over 70 percent of the dataset. Honduras, Russia, Colombia, and Canada followed distantly.

For years, researchers had not documented a single case of someone refusing DNA collection, in part because refusal is a federal misdemeanor punishable by up to a year in prison. But records released under the FOIA show that between January and July 2024, at least 174 people told CBP they would not comply. The government has provided no information about what happened to them afterward.

The July update also detailed how the Trump administration has deepened the integration of DNA surveillance into broader government systems. A March executive order mandated cross-agency information sharing. And with immigration arrests now surging throughout the nation’s interior, the impact of the program is no longer confined to border communities. Increasingly, citizens and long-term residents are at risk of being pulled into the government’s genetic net.

The combined findings of the Center on Privacy & Technology’s reports, combined with other data and disclosures, leave little ambiguity that DHS has amassed millions of DNA profiles under questionable legal authority, siphoning in citizens, minors, and elderly people often without charges or justification, and has embedded the database into a broader surveillance infrastructure creating the foundation for universal monitoring. And it has done all this with minimal transparency, oversight, or accountability.

Congress has the power to repeal the DNA collection provision of the DNA Fingerprint Act or to impose strict limits on DHS and the FBI. Georgetown’s researchers have called for halting the program, purging collected profiles, and banning the use of immigration powers to amass DNA. But political will remains uncertain.

“Congress can and should repeal the federal statute that authorizes DHS to take DNA and pass new legislation comprehensively regulating the collection, creation, storage and sharing of genetic data by both public and private actors,” the researchers said.

In the meantime, every DNA swab adds to a database that is permanent by design. DNA, unlike fingerprints, contains a person’s biological blueprint and family ties. Retained indefinitely, it can be mined in ways not yet imaginable. The blueprint of who we are is now in government freezers and in FBI databases, waiting to be linked, analyzed, and used.

The danger lies not only in how the government uses this data today, but what future administrations may do with it. The story of the DNA Fingerprint Act shows that what was once considered marginal can, with time and opportunism, become central. Twenty years later, the overlooked provision has become the cornerstone of an American genetic dragnet. One that shows no signs of stopping.

Article Topics

biometric identifiers | border security | CBP | data collection | DHS | dna | FBI | law enforcement | U.S. Government

Latest Biometrics News

Sep 24, 2025, 5:23 pm EDT

Age assurance is on New Zealand’s agenda as the country advances its digital identity system and the Trust Framework that…

Sep 24, 2025, 3:49 pm EDT

Political leaders rise and fall, but they never really go away. Former Prime Minister of the UK Tony Blair, now…

Sep 24, 2025, 12:20 pm EDT

The UK is modernizing its Mandatory Licensing Conditions (MLC) with British pubs, shops and clubs able to accept mobile digital…

Sep 24, 2025, 12:02 pm EDT

It’s becoming increasingly clear that social media is at a tipping point. Having captured a huge percentage of the internet…

Sep 24, 2025, 11:56 am EDT

The National Procurement Commission (NPC) of Sri Lanka, in partnership with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), has kicked off…

Sep 24, 2025, 11:22 am EDT

The U.S. Biometric Exit program graduated from a pilot program to production earlier this month with a revision to Customs…