Analysts at the Brussels-based think tank Bruegel recently assessed the fiscal effects of the GOP-passed tax cut and spending reform megabill. Their conclusion is that it made an already challenging fiscal outlook materially worse.

The analysts focus on what it will take to stabilize gross federal debt at various levels in the coming quarter-century. Gross debt includes borrowing from government trust funds (most especially those associated with Social Security and Medicare). The more common measure in the US debate is debt held by the public, which excludes intra-governmental transactions, but most international comparison studies conform to the Bruegel model. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated in the long-term forecast completed before the megabill became law that gross debt would rise from 122 percent of GDP in 2024 to 160 percent in 2050.

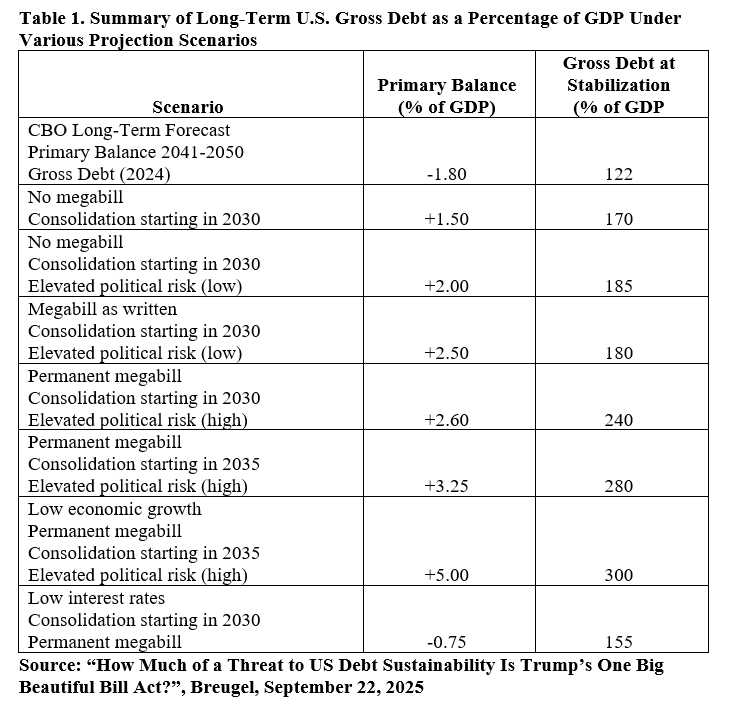

Bruegel’s analysis focuses on the level at which a sustained annual primary budget surpluses or deficits will prevent continued escalation of gross debt relative to GDP. The primary budget excludes net interest payments on accumulated debt. CBO’s long-term outlook estimates the primary budget will run an average annual deficit of 1.8 percent of GDP from 2041 to 2050. Scenarios which model the effects of primary surpluses thus assume tax and spending changes which rather dramatically improve the government’s fiscal position.

Bruegel’s starting point is an April 2025 fiscal and economic projection from the International Monetary Fund combined with CBO’s assessment of the fiscal effects of the megabill. Several additional variables are then considered.

The timing of fiscal consolidation. Changes in primary budget balances begin either in 2030 or 2035.

The possibility of elevated political risks. The volatility and uncertainty introduced by the Trump administration’s tariffs and other unilateral actions might erode growth and deepen the fiscal hole, which Bruegel factors into some scenarios.

Permanent or temporary tax cuts. Bruegel assesses scenarios with the megabill’s temporary tax cuts expiring as planned or remaining in place permanently.

High or low short-term interest rates. President Trump’s push to cut short-term rates would have a large effect on debt projections. Bruegel produces scenarios that assume short-term rates follow the president’s stated preferences (approximately a permanent 2.0 percent short-term rate) and rates which conform to what would occur with traditional Fed governance (4.25 percent).

Faster or slower economic growth. Bruegel models what might happen with markedly slower annual GDP growth.

Table 1 summarizes the study’s findings.

There is considerable uncertainty in any long-term fiscal forecast, but especially in the current environment. In particular, two factors could dramatically alter Bruegel’s projections. First, the Trump administration’s tariffs, if allowed by the courts, might generate substantial additional federal revenue. If that occurred, and the downside effects on the economy were minimal (which is unlikely), the long-term debt forecast would be much less pessimistic.

Second, if artificial intelligence (AI) enhances productivity growth on a sustained basis, as some expect it will, then higher growth might ease fiscal pressures in future years.

With so much uncertainty, and rising risks from further delays, it would be better for Congress to move quickly on a course correction. It will be possible to loosen restraints later if today’s projections prove to be too pessimistic.

Bruegel’s authors stress that the risks from inaction are high. They note that no country has been able to run sustained primary surpluses of 3.0 percent of GDP or more to avoid a debt crisis. If Congress delays starting fiscal consolidation until 2035, it is possible that the US would need to run permanent primary surpluses of over 3.0 percent of GDP just to keep gross debt from rising above 200 percent of GDP.

The wild card is monetary policy. If the Fed were to cut short-term interest rates substantially, as the president has demanded, net interest costs would fall, which would make it less challenging to keep gross debt from rising uncontrollably. With lower interest rates, the Bruegel team estimates the government could run primary deficits of 0.75 percent of GDP each year and still keep gross debt from rising above 155 percent of GDP.

Of course, the economic and fiscal risks from undermining the independence of the Fed are so high they that outweigh any potential benefits from inflating away the government’s debt obligations. That does not mean the temptation is not be real.