A firm favourite topic for Beatles obsessives to kick around during those long-into-the night deliberations is just which of their eleven (we don’t count Magical Mystery Tour or Yellow Submarine, okay!) studio LPs was their singular best.

Whether you’re a Revolver man, an Abbey Road girl or your softest spot is reserved for their 1963 debut Please Please Me (we know there’s a few of you out there), what really isn’t a matter of opinion is that on the wider cultural stage, it remains 1967’s Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band that is the most synonymous with the Beatles at the peak of their powers.

For many, it remains the greatest album in pop’s storied history. It’s certainly one of the most interesting from a technical and band narrative point of view, being the first of the Beatles’ studio-based career.

In fact, it was this vivid cauldron of a record that solidified the very idea of ‘the album’ in popular culture, and underlined its status in devotees as the most crucial component of an artist’s canon.

You may like

“The pop revolution was driven by 45s – an LP ‘the prize’ for success and even then comprising two hits and a lot of filling,” said writer David Hepworth in his album-centred book A Fabulous Creation: How the LP Saved Our Lives.

“It was Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band that changed all that: not merely a collection of songs but an album – though one might call it a song cycle. After Pepper nothing was ever the same again and the acquisition of albums was an essential part of every student’s life.”

Expanding on Revolver’s initial forays into unknown sonic regions tenfold, Pepper found John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr firmly shunning the trappings of their prior identity as a mass market, entertainment spectacle.

Instead, inspired by the pioneering studio work of Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys, they decided to use their hard-won global platform to metamorphose into a creative force the likes of which the world had never seen.

Connecting the musical threads that spanned Britain’s past and present – and rippling with the philosophy of the counterculture – the Beatles recast themselves as the house band of the Summer of Love.

The Fab Four were no more. Enter Sgt. Pepper’s titular psychedelic troubadours, the Lonely Hearts Club Band. This overt casting-off of their previous identity was quite literally depicted by the iconic Beatles-at-their-own-funeral cover art by Peter Blake.

On a strictly musical level, the album’s high points were many. There was the sinister Victoriana of Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite, the heart-string tugging social commentary of the stately She’s Leaving Home and of course, the grand finale’s hallucinogenic collision of high art and acid culture depicted on the sweepingly epic A Day in the Life.

The Beatles had speedily mastered the art of using the studio as instrument, and painstakingly crafted innovative work which left the boundaries of contemporary pop music a distant speck in the rear-view mirror.

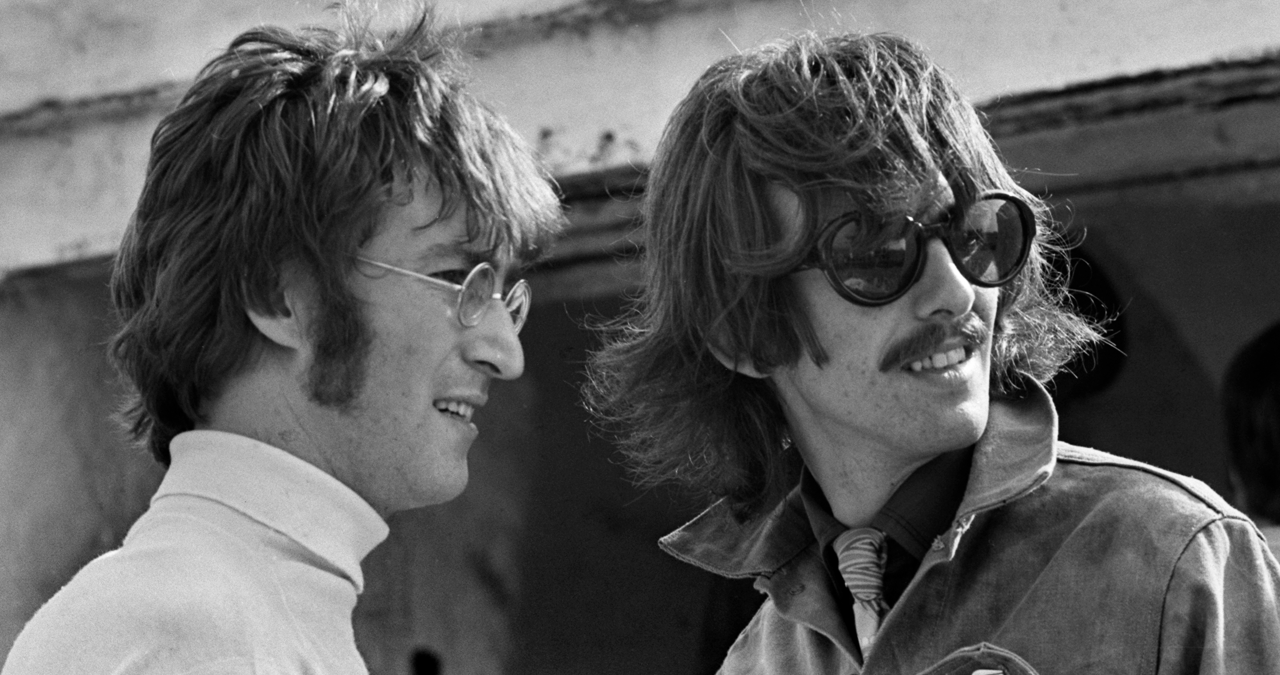

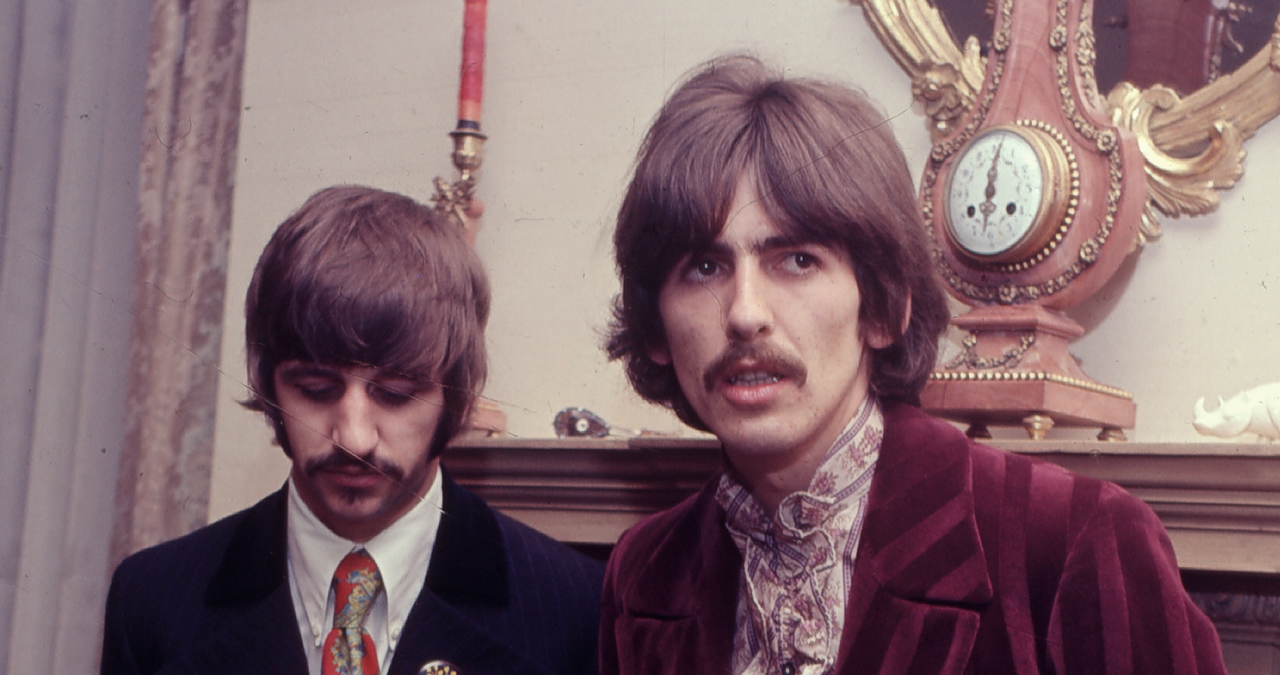

The Beatles in 1967 emerged, bleary-eyed, from EMI Studios with a record that would come to define the era (Image credit: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

At the heart of this kaleidoscopic set lay perhaps its most profound cut. We’re talking about that Indian-instrument suffused second-side opener, Within You Without You, written and performed by George Harrison. With a little help from a few of his, non-Beatle, friends…

Backing Harrison on this most unusual of ‘Beatle’ recordings were an eight-piece string ensemble (corralled by George Martin) and a collection of Indian musicians, playing dilruba (a bowed sitar-type instrument), tamboura (a drone-setting lute, also known as a tanpura), tabla (a pair of hand drums, popular in Hindustani classical music) and swarmandal (a harp-like, plucked-box zither.)

Enchanted by the sitar ever since he had his first cursory dabble (the story goes, that this happened during the making of the Beatles’ second movie Help!), George was eager to lay his guitar to one side and incorporate his new fixation into Beatle songs.

You may like

This ambition had started gently with the sitar’s incongruous, use on Rubber Soul’s Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown), and expanded more overtly with the sparkling Love You Too on Revolver and its defined presence within the swirl of that album’s mind-expanding conclusion, Tomorrow Never Knows.

Within You Without You, though, represented a full-blooded, far-reaching leap into the depths of the Indian classical musical tradition.

Within You Without You (2017 Mix) – YouTube

For passive pop-picking listeners on the 1960s, it would be extremely difficult – ludicrous perhaps – to even countenance that the artist behind this exotic, Indian-instrument defined piece was the very same act that just a couple of years prior had been doling out pop confectionary like I Feel Fine and Day Tripper.

It was during the interim between the group’s announcement that the touring days were over (August 1966) and the beginning of work on Sgt. Pepper (November 1966) when George truly immersed himself in Indian culture. Spending six weeks in India, Harrison was engrossed in the language, traditions, music and spirituality of the formerly British Empire-ran subcontinent.

He returned a changed man.

Hindu philosophy had resonated profoundly with the 23 year-old. In particular was the notion of the Krishna consciousness. “I always felt at home with Krishna. You see it was already a part of me,” Harrison explained in an interview with the Hare Krishna Movement in 1982. “I think it’s something that’s been with me from my previous birth… It had been slowly fitting together.”

When not fervently mantra-chanting or bathing in the Ganges (the river where his ashes would eventually be scattered after his death from cancer in 2001), Harrison took up the challenge of fully mastering the sitar under the tutelage of respected virtuoso, Ravi Shankar.

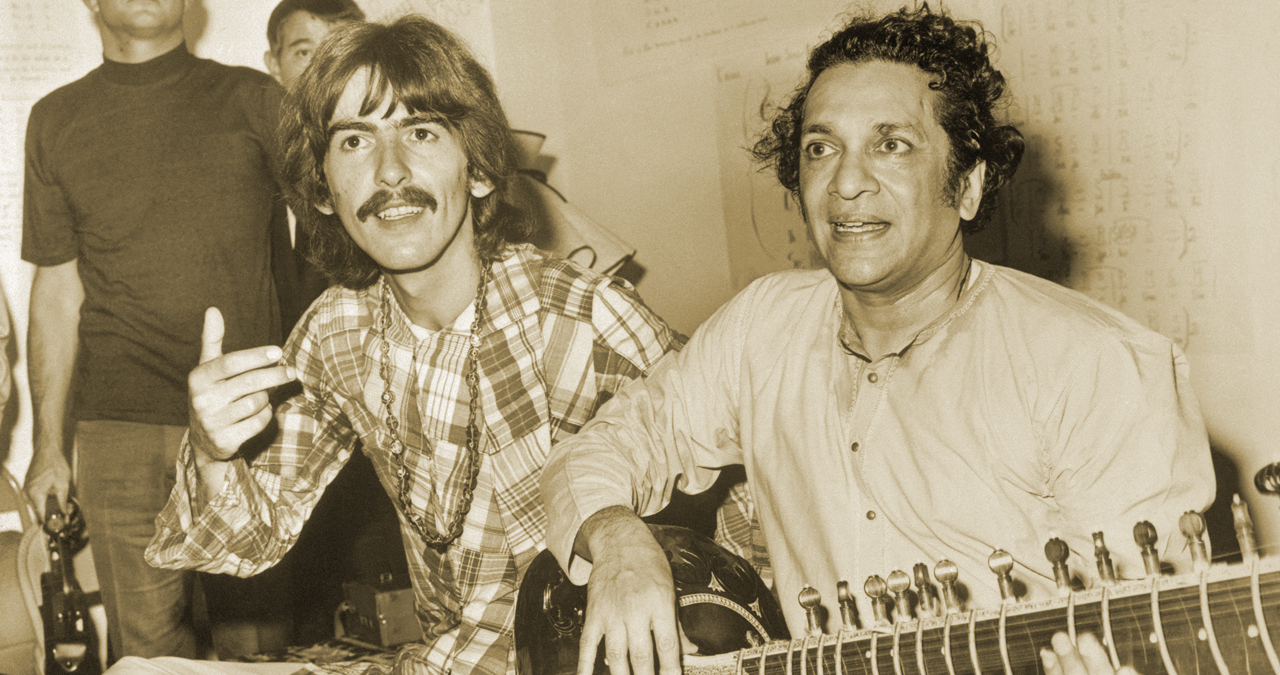

George learned his sitar chops from one of the instrument’s greatest masters, but Ravi Shankar felt the Beatle still had a long way to go… (Image credit: Bettmann/Getty Images)

Under Shankar’s tutelage, Harrison regularly repeated the sargam scale – a run through the notes of the octave that underpin the Indian musical scale (Sa, Re, Ga, Ma, Pa, Dha, Ni).

These daily exercises soon became muscle memory to Harrison, and the gradual note progression ultimately shaped the melodic contours of Within You Without You.

“When George showed his interest in sitar and said he would like to learn a little more, I told him very clearly that sitar is not like guitar where you can just learn it on your own,” Shankar explained in Andy Babiuk’s The Beatles’ Gear. “You have to undergo many years of study, like with the violin and cello or any of the Western classical instruments. It takes ten to fifteen years to reach a good standard, because it is not just the playing of it. You have to learn the whole musical system. So what George did, along with many others, was to take up the sitar and just start to play. They produced a sort of sound that to us sounded really ridiculous.”

“Within You Without You was written after I had got into meditation,” George recalled in his 1980 book I Me Mine. “We had entered into the All You Need Is Love consciousness after the LSD period. The song was written at Klaus Voormann’s house in Hampstead, London.”

Voormann, an artist and musician, was a longtime friend of the band since the Hamburg days, and the artist behind the Revolver cover. They two men had been discussing characteristically weighty subjects, namely the idea that invisible forces permeate the world. During a lull in the conversation, Harrison noticed his old friend’s recently acquired harmonium.

Curious, George asked Klaus if he could have a tinker.

“[That’s] when the song came to me,” remembered George in I Me Mine. “The tune came first, then the first sentence, [‘We were talking about the space between us now’] I finished the words later.”

The lyrics that poured from Harrison were reflective of his spiritual renewal in India, and a newly-attuned radar for those enigmatic forces that he believed swam in the spaces we couldn’t see.

These weren’t just the esoteric concerns of the East, Harrison felt, but they pervaded the lives of ordinary people in the West, too.

The problem was, in George’s view, that many couldn’t, and never would, be aware of these imperceptible bonds. Partly because they didn’t want to, and partly because of the distractions of the modern world.

We were talking about the space between us all

And the people who hide themselves behind a wall of illusion

Never glimpse the truth

Then it’s far too late

When they pass away

“There are so many people who don’t understand the sentiment of Within You Without You,” Harrison explained in the Beatles Anthology. “They can’t see outside themselves, they’re too self-important and can’t see how small we all are.”

These themes, though broadly critical of the erosion of spirituality, also jibed strongly with the overall, consciousness-raising philosophy of acid-advocating intellectuals like Timothy Leary. The song’s intimation of ‘the truth’ corresponded with Leary’s concept of ‘ego death’, the notion that blurring the boundaries of the self via psychedelic substances was key to tapping into a deeper truth.

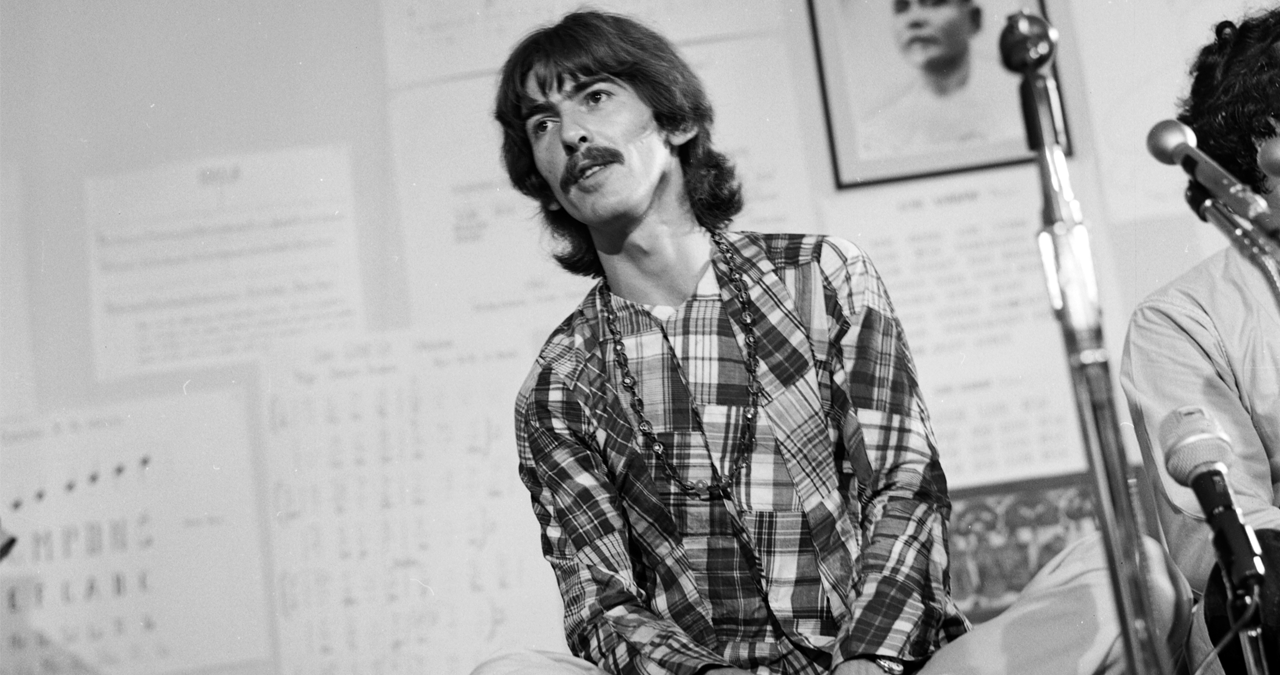

Harrison’s sole songwriting contribution to Sgt. Pepper underlined his musical and spiritual fixation with all things India (Image credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

These types of philosophical ideas were becoming trendy as the utopian, hippie movement began to gain prominence.

This was, perhaps in part, a reaction against the horrendous, televised images of horror taking place in Vietnam that were then being played out in living rooms across the Western world. The youth had naturally started to question government, and the established order of things.

Back to the Beatles, and despite being relieved to no longer have to go out on tour, Harrison was missing the band cohesion during the more technically-demanding Sgt. Pepper sessions. “Sgt. Pepper was the one album where things were done slightly differently,” Harrison reflected in The Beatles Anthology. “A lot of the time, we weren’t allowed to play as a band so much. It became an assembly process – just little parts and then overdubbing.”

This yearning for yesteryear certainly wasn’t at the forefront of Harrison’s mind when it came to working to the album’s Paul McCartney-directed concept (which George had little interest in), and Within You Without You was developed distantly from his bandmates.

“My heart was still out there [in India]”, Harrison was quoted as saying in The Beatles Anthology. “[Working with the Beatles again] felt like going backwards.”

This feeling of detachment was further compounded by the fact that his first song pitch for the group’s eighth LP, Only a Northern Song (which would later appear on the soundtrack to Yellow Submarine) was dismissed by the Beatles’ producer George Martin as ‘Too boring’.

Only A Northern Song (Remastered 2009) – YouTube

Martin instructed Harrison to ‘come back with something better’ for his one and only contribution to the record. That had to sting.

Fuelled by this rejection, Harrison turned to working his idea for Within You Without You into what is surely in the running for the most audacious piece of music on the album.

It was a piece of creative retribution that sounded unlike anything that had ever been heard before on a chart-topping Western pop record.

As George further recounted in the Beatles Anthology, the arrangement of Within You Without You was based upon a piece of music that Ravi Shankar had recorded for All-India Radio. “It was a very long piece – maybe 30 or 40 minutes – and was written in different parts, with a progression in each,” recalled Harrison. “I wrote a mini version of it, using sounds similar to those I’d discovered in his piece. I recorded in three segments and spliced them together later.”

Principally recorded on March 15th 1967 within Abbey Road’s Studio 2 (then known as EMI Studios), Harrison went all-in on setting the appropriate mood.

Decking out the studio with Indian tapestries, Harrison turned down the lights, lit some incense and attempted to conjure the distinctly Eastern vibe that he hoped would infuse the track.

Seasoned Beatle-engineer Geoff Emerick aided Harrison, digging out some of Abbey Road’s tatty throwrugs so the instrumentalists could sit and play together, emulating a traditional set-up.

“The Abbey Road throwrugs were completely moth-eaten and dilapidated… but it was the thought that counted,” Emerick recollected in his book Here, There and Everywhere.

Performed on the track were a pair of tamboura (two were played by Harrison himself alongside Beatles’ road manager Neil Aspinall) whilst the tabla, two dilrubas and an additional tamboura were performed by Amiya Dasgupta, Anna Joshi, Amrit Gajjar and Buddhadev Kansara respectively.

These musicians were all members of the Asian Music Circle – a London-based group which had been set-up to promote Indian and Asian styles of music and dance in Western culture. What better conduit to the ears of the West than its biggest band’s eagerly anticipated new album.

Additional overdubbing would expand the instrumental palette further with the addition of the swarmandal, which is used to weave the glissando, harp-like ornamentation at the song’s start. There was also space for Harrison to, of course, beautifully thread his sitar.

Following a ‘marathon’ recording session, George’s dreamy lead vocal was tracked early in the morning of the next day.

“George tackled the lead vocal, and he did a great job. Mind you, he does sound quite sleepy on it,” recalled engineer Geoff Emerick in Here, There and Everywhere. “[It’s] hardly surprising since he’d been up all night working on the track! Fortunately, that lethargic quality seemed to perfectly complement the mood of the song.”

Emerick also illuminated how he close-mic’d the tablas, and added signal processing to make them a little bit more sonically exciting. “Everyone was amazed when they first heard a tabla recorded that close and with the texture and the lovely low resonances.”

“It was not a commercial song by any means,” producer George Martin later recalled. “But it was very interesting. [George Harrison] had this way of communicating music by the Indian system, a seperate language almost. [Sounds] like ‘tiky tiky ta ta taaa’, which came from the rhythms suggested by the tabla player. You had to get inside that and work out what it was about.”

Directing proceedings based on a memorised structure, Harrison’s composition oriented around the Khamaj thaat (the Indian equivalent of the Mixolydian mode), Within You Without You’s music etched its way atop a constant drone that gravitated around C (later sped up to the key of C# when being edited for time). Harrison’s serene, undulating vocal melody was mirrored by the dilruba – a typical approach in many Indian music forms.

Meanwhile, the propulsive tabla rhythms were grounded in a 16-beat rhythm known a tintal during the verse and chorus, played at a medium tempo.

This was a pattern similar to 4/4, yet differed as one measure encompasses the entire 16-beat cycle. Its steady, symmetrical pattern kept a 16-beat (4+4+4+4) pulse throughout the main part of the song.

During the middle-section, this tabla beat entered into an organic call-and-response interplay with the other instruments in 5/4 time, an approach referred to in the Indian classical musical tradition as jawab-sawal (question/answer), before ultimately landing back on the 16-beat tintal rhythm of the opening.

Harrison’s deep study of Indian musical forms was in obvious evidence, but there was another element that elevated the track even further…

Tabla (Image credit: Elio Guidi/Getty Images)

The final magic touch came with the ingenious decision to marry these traditional Indian techniques with instruments typically found in the West.

George Martin’s inspired string ensemble, tracked on the final day of recording for Sgt. Pepper, united eight violins and three cellos from the London Symphony Orchestra to complement, contrast, mimic and blend with the Indian landscape.

The two Georges worked tirelessly to find the common linkage between the instruments, painstakingly mapping the swooping and bowing of the dilruba’s movements and carefully communicating the microtonal slides to the English ensemble.

The resulting interplay bridged these two, very different, musical traditions. It was, essentially, a divine handshake between West and East in sound.

Although an impressive technical accomplishment, the instrumentation echoed the underlying lyric’s philosophical intimation that deeper powers bond every human being, regardless of culture and geography.

“I found it very fascinating actually working with George on that,” George Martin stated in an interview, shared below. Him trying to get from English musicians what the Indians were already giving us. It started with George working with a dilruba player.”

Within that same video, Martin demonstrated how their work entwined the dilruba and violin, and how George Harrison ‘answered’ on sitar. He points to the pizzicato strings and a ‘slurpy’ cello as being examples of how they managed to find the connective tissue between distinct musical languages.

Although the song was hugely different to everything else on Pepper, Harrison’s only concession to the record’s loose theme was the addition of humoured crowd noise [Taken from Abbey Road’s sound effect collection, Volume 6: Applause and Laughter] at the song’s end.

Although initially added to relieve the heaviness of the track’s grander themes, Harrison judged that it also worked in reference to the supposed context of the surrounding record. “You were supposed to hear the audience anyway, as they listen to Sgt. Pepper’s Show,” Harrison told Hunter Davies in his authorised biography.

As the opener to Sgt. Pepper’s second side, Within You Without You was quite the most unexpected turn a Beatles album had taken to date.

It demonstrated the full reach of George Harrison’s musical abilities. A studious, questing talent that was further proved via the fruits of his work across the next few Beatle records. A blinding array of songs that included While My Guitar Gently Weeps, Here Comes the Sun and Something.

Whilst some contemporary listeners were unsurprisingly baffled by the track (some still are), and derided its musical aspirations as pretentious, an equal number fell under its spell.

Ringo sat this one out, much to his relief (Image credit: Mark and Colleen Hayward/Getty Images)

“This ambitious essay in cross-cultural fusion and meditative philosophy has been dismissed with a yawn by almost every commentator since it first appeared,” wrote the late Beatles-scribe Ian MacDonald in his still-essential Revolution in the Head. “[But] Within You Without You is central to the outlook that shaped Sgt. Pepper. Stylistically, it is the most distant departure from the staple Beatles sound in their discography – and an altogether remarkable achievement for someone who had been acquainted with Hindustani classical music for barely eighteen months.”

Despite not contributing to the song, John Lennon was a notable presence in the studio on the day it was recorded. Although he, according to Geoff Emerick, looked bored during the session, Within You Without You would strike a chord with Lennon, and stand up as one of his very favourite George songs, even over a decade later.

“He’s clear on that song,” John Lennon would later enthuse of Within You Without You in his Playboy interview in September 1980, just three months before his tragic murder. “His mind and his music are clear. There is his innate talent. He brought that sound together.”