Does anyone remember how we kicked off postseason baseball in the 2000s? We bet Greg Maddux does.

He started for the Braves against the Cardinals in Game 1 of the 2000 postseason — and somehow gave up hits to the first four hitters he faced! If that seems unbelievable, how about this: He would win only one more postseason game over the rest of his career.

So why will you not find Maddux’s name on our brand new postseason edition of the MLB All-Quarter Century Team? That’s why!

At least that decision about who belonged on this team was easy. But as for the rest of these? Yikes. Most of them felt practically impossible.

Not that that stopped us. It was our responsibility to you, our loyal readers, to finish off our season-long All-Quarter Century Team series by doing all we could to annoy, enrage and flabbergast you, with these picks for the postseason version of this team.

We think we’ve done that. So here are our choices — which even we didn’t agree on initially. Luckily, we’re confident that everyone reading this will be in full agreement. But if for some reason you’re not, just let us know in the comments section below. We’ll start ducking for cover.

And yes, we’re aware of the technicality that the year 2000 was actually the end of the previous century, not the start of this one. But can we all agree that 1999 was the end of the 1900s, and 2000 was the beginning of the 2000s? In selecting this team, we looked at postseason performance from 2000 through 2024.

Oh, and one more thing: The position-player part of this was a Stark writing assignment. The pitchers section was a Kepner production. Not that it matters to most of you, but if you think any of these picks are dopey, disgraceful or just outright wrong, our stance will be: Don’t blame me. It was HIS fault.

First base: Albert Pujols

Albert Pujols, the NLCS MVP in 2004, gets the nod at first base. (Tom Gannam / Associated Press)

Yeah, we could have gone with Freddie Freeman here — if walk-off grand slams were the 2-billion-bonus-point tie-breaker. But with all proper admiration for Freeman, the winner here has to be Sir Albert.

Compare the postseason credentials for these two and you’ll see.

CATEGORYPUJOLS FREEMAN

HR

19

14

AVG

.319

.277

OBP

.422

.373

SLUG

.572

.519

OPS

.995

.893

RBI

54

36

RUNS

57

31

INT BB

20

3

They each were the first baseman on two World Series winners. And they each have postseason MVP trophies on their shelves (although Freeman was a World Series MVP, while Pujols “only” won an NLCS MVP). So if you’d like to tell us they both deserve this, you’re right. But if there’s an argument in there that Pujols shouldn’t win, sorry. We couldn’t find one.

Second base: Jose Altuve

All right, let it all out. Go find your trash-can lid and bang it. Go hook up your favorite buzzer and push it. Go find your asterisk collection and spray it in our direction. Yes, we know how obsessed thousands of you are with the clouds that hover over the 2015-24 Astros.

Got it. Duly acknowledged. Appreciate your concern. But just as we didn’t disqualify Altuve from his spot on the regular-season version of this team, we’re ruling he’s equally eligible for the Mr. October Club.

And if he’s eligible, then guess what? He has to be the second baseman on this team if only because … he’s one of the greatest postseason hitters of all time.

He’s 5-foot-6 … and he’s hit 27 postseason homers. He ranks in the top four, among all postseason players ever, in hits, runs, homers and total bases.

He has piled up more postseason hits and homers (27 and 118) than Chase Utley and Dustin Pedroia combined (95 and 15). And he owns the highest 21st-century postseason OPS (.841) of any full-time second baseman who has won at least one World Series.

We know there are questions about the Buzzergate stuff that lingers around his greatest October moment ever — the shocking, game-ending, next-stop-is-the-World Series homer off Aroldis Chapman in 2019. But we don’t recall the league stripping him or his team of any hits, homers, wins or titles.

So here’s the deal: That … happened. And since it did, there’s just not a compelling enough case for anyone else — not Utley, not Pedroia, not Robinson Canó, not bounce-around-the-field types like Kiké Hernández and Ben Zobrist. Sorry. You know where to express your alternate viewpoints.

Shortstop: Derek Jeter

This one seemed so obvious … but was it?

Corey Seager: two-time World Series MVP. And how exclusive is that list? The only guys on it are Seager and three Hall of Famers (Bob Gibson, Reggie Jackson and that Sandy Koufax guy.)

But also … Carlos Correa: 18 postseason homers — two of them unforgettable walk-off bombs. And was he clutch enough for you? According to Baseball Reference, he ranks No. 3 all time in postseason Win Probability Added. That seems good.

So there was so much to ponder, until that lightning bolt zapped us, as if to ask: What the heck are you dopes thinking?

Of course, Derek Jeter is the shortstop on this team. He was the MVP of the first World Series in the 2000s. He was a human October highlight reel — and he was Mr. November.

We also thought about this: Suppose Francis Ford Coppola wasn’t available, and we were asked to produce the epic major motion picture on postseasons in the 2000s, “The Lord of the October Rings.” Wouldn’t the very first player on the screen be The Captain of the New York Yankees?

He didn’t just live for October. He was October. And as he’s said so many times, he rose to those moments because he was always himself in those moments.

Jeter in the 2000s

AVGOBP SLGOPSHR*RUNS

Postseason

.301

.366

.467

.833

23

109

Regular season

.307

.374

.432

.806

15

110

(*per 162 games)

OK, case closed. Apologies to Seager, Correa and yes, even David Eckstein.

Third base: David Freese

The David Freese Game is one for the history books. (Doug Pensinger / Getty Images)

Have you noticed that all the choices so far were the same players who populated three-quarters of this infield on our regular-season All-Quarter Century Team? Well, even if you hadn’t, that trend ends here.

When we began to consider third base, we realized we had an important philosophical debate to sort out. Is this going to be a Career October Achievement Award? Or are we allowed to be swayed by the shorter-term case for a guy who, let’s just say, has his own World Series game named after him?

Do we really have to remind you about The David Freese Game? Game 6, 2011 World Series. Not just a tremendous evening of October theater. Might even be the greatest World Series game ever played.

And we can thank the third baseman for the Cardinals, who fired a game-tying two-out, two-strike triple in the ninth and then a staggering, season-saving, history-rewriting, walk-off homer in the 11th. The Cardinals won an improbable World Series because Freese did those things.

And as you can see, we came around to the idea that a World Series MVP who airlifts his team onto the parade floats can make this lineup — even if it’s mostly for that. You know why? Because nothing about the postseason matters more than that.

That said, Freese was a great October player, period. Only five third basemen in postseason history hit more homers than he did (10). His career postseason OPS was .919. His career World Series OPS was .962. And he ranks No. 1 in history in career postseason Win Probability Added.

So even though we had some great choices at this position (Pablo Sandoval, Troy Glaus, Mike Lowell, Alex Bregman, even Alex Rodriguez), we’re making a statement with this pick.

Left field: Kyle Schwarber

Kyle Schwarber, pictured in the 2016 World Series. It’s not October if he’s not playing. (Elsa / Getty Images)

We could have gone with Barry Bonds, except whoops — he never won a World Series. We could have gone with Randy Arozarena, except … see above. We decided when we started this project that winning it all at least once was the non-negotiable cutoff point.

So this wound up coming down to Schwarber versus Manny Ramirez (with Hideki Matsui somewhere in that mix). And on one level, it was hard not to go with the guy with the .338/.442/.604 slash line (Ramirez).

But as we mentioned in the regular-season portion of this project, we had a different standard for “PED guys” who got dinged after the testing era kicked in. And Manny’s most dominant October of them all came with the 2008 Dodgers, when he hit .520, with a ridiculous 1.747 OPS. Whereupon … he tested positive the next spring training!

So that led us to Schwarber, and why the heck not. The only complication is that he also has DH’d and even played first base at this time of year. But he played left field more than any other position, so that was another one of our qualifiers.

And since he qualifies in this spot, he’s in. You know who this generation’s true Mr. October is? The Schwarbino! It’s not October if this guy isn’t playing. In his first 10 big-league seasons, he suited up in the postseason in nine of them — and he’ll do it again any day now.

But also … only three players have hit more postseason homers than he has (22). No one has led off more postseason games with a homer than he has (five). And Schwarber has this awesome claim to fame: He has homered in every possible postseason series — World Series, NLCS, ALCS, NLDS, ALDS, NL wild card and AL wild card.

Plus he allows us to elevate at least one guy from the curse-busting 2016 Cubs into this lineup. So why not the dude who tore up his knee, was supposed to be out for the year and then willed himself to heal up, come back and hit .412 in that World Series?

Will this honor earn him an extra $10 million or so as a free agent this winter? Ya never know.

Center field: George Springer

Yet another dastardly member of the Trash Can Astros makes this team. And we apologize to the runners-up — Bernie Williams, Jim Edmonds, Darin Erstad, Johnny Damon, etc. — for not punishing heinous can-banging mischief the way America seems to want us to.

But refer back to the Altuve section of this piece for a reminder on our reasoning. As long as the sport was going to allow all the Astros’ October glories to stand, Springer was impossible to leave off this team.

Couldn’t overlook those 19 postseason homers. Sorry. Couldn’t pretend that World Series MVP award never happened. Sorry.

Only one player in the 2000s (Altuve) has hit more postseason home runs that either tied a game or gave his team the lead than Springer hit (10). His career postseason OPS is 1.023 with men in scoring position, 1.308 in one-run games and 1.295 in 14 World Series games. (And for the record, his leadoff double and second-inning homer essentially won Game 7 of that 2019 World Series … about 1,500 miles away from those trash cans in Houston.)

So America, we hear you. We’re just doing what we have to do, as much as that seems to irritate you. One more time: Sorry!

Right field: Lance Berkman

Hey, we bet you didn’t expect to see this choice. This was another fun debate, with Mookie Betts, Carlos Beltrán, Jayson Werth, Jermaine Dye and even Juan Soto giving us lots to think about.

So how did Berkman rise to the top of that heap? Well, he was already possibly the least-hyped great player of this century. So we might as well honor him for something.

Did you know that Berkman’s career postseason slash line was .317/.417/.532/.949? That’ll work. He played in five postseasons — and hit .300 or better in four of them. And his career postseason on-base percentage (.417) ranks No. 1 among every right fielder who has won a World Series in this quarter-century.

OK, now let’s talk about that World Series his 2011 Cardinals won. Freese wasn’t the only October hero in Game 6 who rescued the Cardinals from one-strike-away catastrophe. That night Berkman became the only player in history to get a game-tying hit in extra innings with his team one strike away from losing the World Series.

He hit .423/.516/.577 in that World Series, coming to the plate 31 times and reaching base in 16 of those at-bats. And here’s one more Did You Know: He ranks No. 3 all time in Championship Win Probability Added. Only Mickey Mantle — and Freese — are ahead of him.

So Beltrán’s overall numbers (.307/.412/.609) may look more compelling. But the only time he won a World Series, for those 2017 Astros, he was just a bit player — and also was the only player ever directly tied to those trash cans in MLB’s summation of its investigation.

This wasn’t easy. But we get paid to make the hard choices around here. If you don’t agree, just tap your trash can. We’ll listen.

Catcher: Carlos Ruiz

We went into this thing expecting Buster Posey to strap on his gear and step into this spot in our lineup. But that isn’t where we landed. And not just because we love to surprise and aggravate you.

Posey would have been a fine choice, based on his three rings alone. Except he was also a guy with a .230/.288/.328 slash line in those three World Series.

Yadier Molina, our regular-season pick for catcher of the quarter-century, would have been another easy choice, since he won two World Series himself and had memorable swings of the bat in both of them. We love and appreciate Yadi. But we went with somebody else.

Carlos Ruiz wasn’t the biggest star on those 2007-11 Phillies. And he definitely wasn’t the loudest. But he had a huge October presence. His teams won one World Series and played in another. He had a walk-off World Series hit. (Who cares if it traveled about 26 feet.) And he caught the only complete-game postseason no-hitter since Don Larsen (by Roy Halladay in 2010).

Just 10 men have caught at least 50 postseason games in the 2000s. Ruiz is the only one of them with an .800-plus OPS (.802). He’s also rocking a .353/.488/.706/1.194 World Series slash line. And he was the heartbeat of a Phillies juggernaut that deserves some sort of presence on this team.

So yeah, it would have made lots of you happy if we’d gone with Posey, Molina or even Jorge Posada. But you know that guy they called “Chooch?” He was better than you think.

DH: David Ortiz

David Ortiz, the most clutch postseason hitter ever. (Ezra Shaw / Getty Images)

Do we even have to explain this? It won’t take long.

Here’s David Ortiz’s OPS in his three postseasons that led the Red Sox to the duckboats:

2004 — 1.278

2007 — 1.204

2013 — 1.206

Now here come just those three World Series:

2004 — .308/.471/.615

2007 — .333/.412/.533

2013 — .688/.760/1.188

If Win Probability Added is a tool that can help us answer the question — Who’s the most clutch postseason hitter ever? — then the answer is Big Papi. He ranks No. 1 in the history of baseball – and did it for a team that was consumed by curses and ghosts until he showed up.

So if you were worried that nobody from those Red Sox teams was going to crack this glorious roster … never mind!

Pitching staff

The last game of the first 2000s postseason brought Al Leiter to his knees. Leiter, the Mets’ redoubtable lefty, had thrown his 142nd and final pitch of the night — a bouncer up the middle that spun him around as he watched the World Series skip away with two outs in the ninth inning of Game 5.

Leiter took a hard-luck loss for his gem as the Yankees wrapped up the title. His start was the 11th of the 2000 postseason to last more than 120 pitches — a once-common threshold no pitcher has reached since Justin Verlander in Game 2 of the 2017 ALCS.

Verlander’s gem was the last of the 35 postseason complete games in the 2000s — and all five starters on our team threw at least one shutout. It’s a staff so dominant that some big-game stalwarts, like Chris Carpenter and others named below, didn’t quite make the cut.

We still see standout individual performances these days. Starters threw shutout ball 14 times in the last postseason — in outings ranging from two innings (Matthew Boyd) to seven (Jack Flaherty, Michael King, Tarik Skubal, Zack Wheeler). It’s just more of a team effort now, with setup men like Andrew Miller (2016), Bryan Abreu (2022) and so many others playing bigger roles than ever.

In the 2020s, we’ve seen starters pulled from World Series no-hitters after five innings (Atlanta’s Ian Anderson, 2021) and six innings (Houston’s Cristian Javier, 2022). How far could they have gone with those no-hit bids? We’ll never know. But their teams won those starts and wound up on parade floats, and that’s what matters most in the end.

So here’s our pitch — the All-Quarter Century Team postseason pitching staff, starting with the starters, with Tyler at the keyboard …

Madison Bumgarner

Madison Bumgarner, with Buster Posey, after winning Game 7 in 2014. (Jamie Squire / Getty Images)

Bumgarner was wired to win when it mattered most. He was very good in the regular season: 134-124 with a 3.47 ERA. He was otherworldly in the World Series: 4-0 with a record 0.25 ERA and a spellbinding five-inning save for the Giants in Game 7 in Kansas City.

And that’s not all: Bumgarner also had two road shutouts in wild-card games and was the NLCS MVP in 2014. In an interview a few years ago for “The Grandest Stage: A History of the World Series,” Bumgarner said his comfort in the spotlight came from childhood.

“Ever since I was a kid, when people would say there was pressure, I just didn’t buy it,” he said. “I am the pressure. That was the thought in my head. What I mean is, I am the pressure on you. I believed that then, and I still do. It’s easier now to believe it, but I always did.”

You got the idea that Bumgarner was different in 2010. Bruce Bochy summoned him for relief in a raucous NLCS Game 6 in Philadelphia. It wasn’t smooth, but Bumgarner left the bases loaded in the fifth, stranded a runner at third in the sixth, and the Giants went on to clinch the pennant. Then he threw eight shutout innings to win Game 4 of the World Series in Texas.

Back in the World Series in 2012, against Detroit, Bumgarner beat the Tigers with seven shutout innings in Game 2. Two years later he was all but untouchable, working a staggering 52 2/3 innings in October with a 1.10 ERA, two series MVP awards and his third championship ring.

Randy Johnson

It was one of those surreal, only-in-Cooperstown moments. A few weeks ago, the night before the annual Hall of Fame induction ceremony, Johnson stood in the plaque gallery admiring the plaque of Christy Mathewson.

Mathewson was the first pitcher to earn three wins in a best-of-seven World Series, back in 1905. Johnson was the most recent to do it, in 2001.

“Yeah,” Johnson said. “But one of mine was in relief.”

OK, so the Big Unit didn’t spin three shutouts in the span of six days, like Mathewson did. But in the 2001 Series, he shut out the Yankees in Game 2, humbled them again with seven strong innings in Game 6 — and marched from the bullpen the very next night to retire all four hitters he faced. Three appearances, three victories, one Arizona Diamondbacks championship.

Oh, and he did all that after beating two other Hall of Famers — Maddux and Tom Glavine — in a similarly overpowering NLCS performance against the Atlanta Braves. (All told in 2001, Johnson pitched 291 innings and struck out 419. That’s not a typo.)

The rest of Johnson’s postseason nights didn’t go so well in the 2000s: He was 0-2 with a 7.11 ERA for Arizona and the Yankees. But you can’t cut a guy who can look at Christy Mathewson’s plaque and say to himself, “Yep, I did the same thing he did.” That’s a fitting snapshot of greatness.

Curt Schilling

When Schilling pitched for the Phillies in the 1990s, he bonded with pitching coach Johnny Podres. Decades earlier, Podres had lifted the Brooklyn Dodgers to their only championship with a shutout at Yankee Stadium in 1955. Schilling absorbed his lessons about October.

“He talked about everything good that’s gonna happen when you’re in the postseason, so I never looked at it as a terrifying, potential failure,” Schilling once said. “Johnny told me, and I always said it, ‘One game in the postseason can make you famous for the rest of your life.’ When you say Reggie Jackson, what do you think? Three home runs in a World Series game. When you say Johnny Podres? Game 7 shutout. And so I looked at every start as an opportunity to be remembered forever.”

Schilling’s star turn under Podres, in the 1993 postseason, was just an appetizer for his heroics in the 2000s. In 15 starts for Arizona and Boston, Schilling went 10-1 with a 2.12 ERA, the only loss coming in the 2004 ALCS opener when his ankle was crumbling beneath him.

He returned for Game 6, keeping Boston’s comeback train rolling while blood seeped through his sock. Then he won in the World Series, because of course he did: In five World Series starts in the 2000s, Schilling was 3-0 with a 1.38 ERA.

From his 20s to his 40s, if you needed a win in the big game, Schilling was your guy.

Josh Beckett

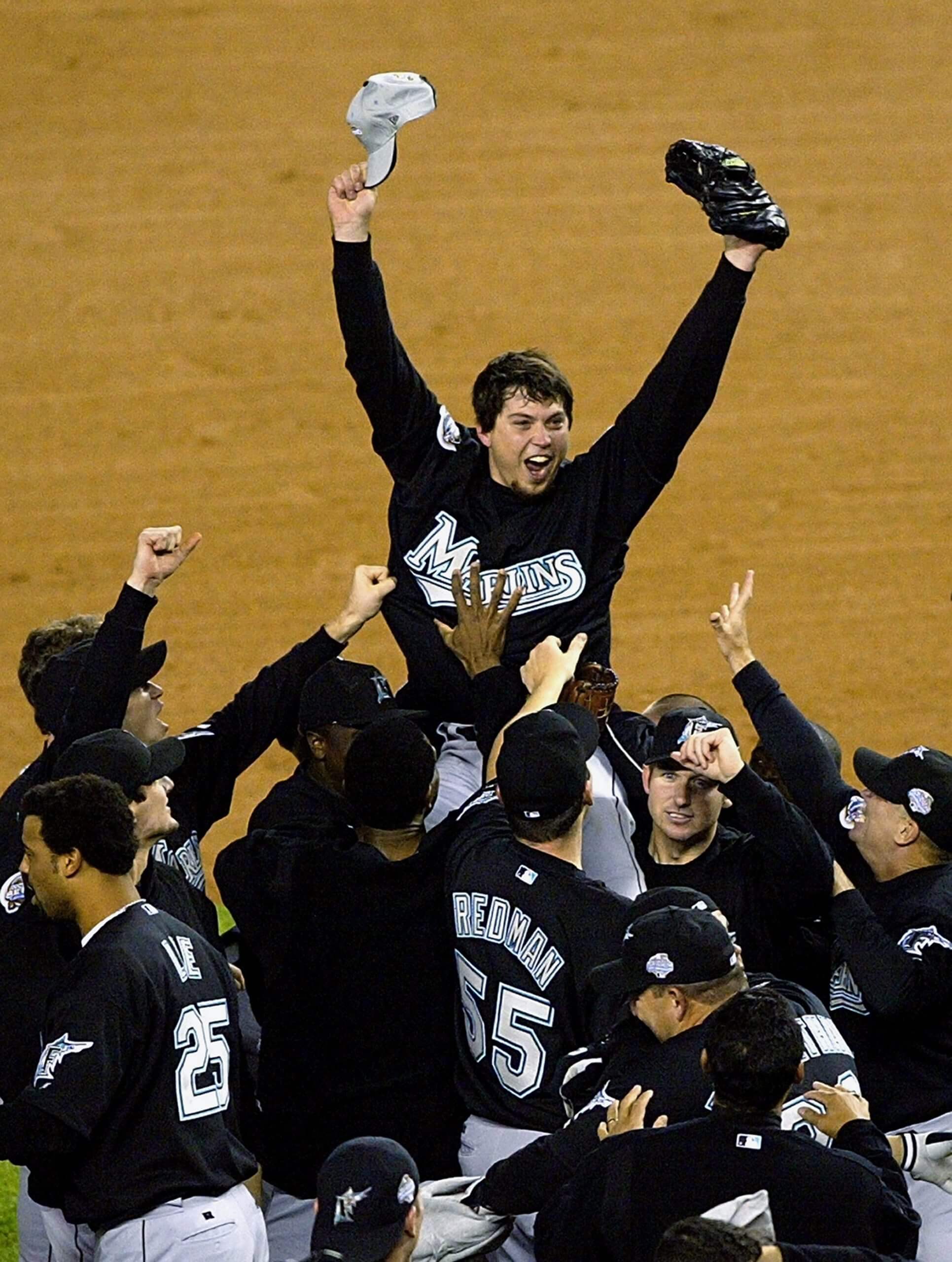

Josh Beckett’s Game 6 shutout lifted the Marlins to the 2003 title. (Jamie Squire / Getty Images)

When you witnessed Beckett with the Florida Marlins in October 2003, you got the feeling he just didn’t know any better. He was 23 years old, cocky and carefree. Two days after an NLCS shutout, he worked four dominant innings of relief at Wrigley Field in Game 7. Then he was MVP of the World Series.

Beckett pitched with a competitive nonchalance that made him seem like the last person on Earth to be intimidated by anything. Need nine innings on three days’ rest to close out a title in the Bronx? Sure, no problem. He was practically oblivious to what he’d done.

“I can’t believe we don’t have a game tomorrow,” Beckett said after his 2-0 masterpiece in the final World Series game at the old Yankee Stadium. “That’s kind of the weird thing right now. Not to say that winning the world championship is not a big thing, but like, we just — we don’t have a game tomorrow. We played this whole season, everything like that, so it’s kind of a relief to get to go deer hunting now. Look forward to that.”

Imagine rooting for a team that hadn’t won in forever, feeling really optimistic about your three-games-to-one LCS lead — and then seeing Beckett on the mound. In 2003, Beckett shut out the Chicago Cubs in Game 5. Four years later, with Boston for another Game 5, Beckett overpowered Cleveland on the road. Neither opponent would win again, as if Beckett had broken their spirit. He was the bringer of doom.

In that 2007 postseason, Beckett earned his second ring by winning all four starts with a 1.20 ERA. He wasn’t as sharp in the next two Octobers, but by then his reputation was secure: Josh Beckett was the guy who broke your heart.

Cole Hamels

We went with Hamels, but the last starter’s spot was the toughest choice on the team.

There’s a fellow changeup master from San Diego, Stephen Strasburg, who took the Washington Nationals all the way in 2019. Strasburg went 5-0 with a 1.98 ERA and won the World Series MVP award that fall. But in the Nats’ first three playoff trips — 2012, 2014 and 2016 — he worked a total of five postseason innings.

And what about Andy Pettitte, who was 13-7 with a 3.34 in 30 starts across 188 2/3 innings? That’s a very Andy Pettitte kind of season — actually a little better … but it’s all in postseason play in the 2000s! Incredible. And it’s a big reason we both check Pettitte’s name on our Hall of Fame ballots.

Jon Lester would like a word, too. All he did was go 4-1 with a 1.77 ERA in six World Series games, earning three rings with the Red Sox and Cubs. Yes, he fell apart in the eighth inning of the 2014 Wild Card Game for the A’s, who had traded for him specifically to change their postseason narrative. But almost every other start was excellent, and Lester’s overall ERA was 2.51.

Hamels, Pettitte and Lester all have an LCS MVP award in the 2000s. And Pettitte and Lester both had a World Series in which they won twice (one of Pettitte’s victories in 2009, in fact, came over Hamels in Philadelphia).

But Hamels won a World Series MVP award in 2008, when he lifted the Phillies to the championship and ended a quarter-century title drought for the city. He also finished off a Division Series in 2010 with a five-hit shutout in Cincinnati, and worked six shutout innings to beat the Cardinals in that round the next fall.

Mostly, though, this comes down to 2008, when Hamels absolutely owned October. Here’s how his five starts went:

Game 1, NLDS vs. Brewers: 8 innings, 0 runs, win

Game 1, NLCS vs. Dodgers: 7 innings, 2 runs, win

Game 5, NLCS vs. Dodgers: 7 innings, 1 run, win

Game 1, World Series vs. Rays: 7 innings, 2 runs, win

Game 5, World Series vs. Rays: 6 rain-soaked innings, 2 runs, no-decision

The Phillies would win that suspended fifth game two nights later, giving Hamels an unblemished October for the ages.

Left-handed setup man: Jeremy Affeldt

Affeldt had already established himself as a postseason force before 2014. In 22 games for the Giants and Colorado Rockies, Affeldt had a 1.37 ERA while helping San Francisco win two titles.

Then came October 2014 — better known as The Madison Bumgarner Postseason — when Affeldt did something wonderfully bizarre: He pitched in every inning, from the second through the 10th. And nobody scored on him.

Affeldt pitched in 11 games and entered in seven different innings. He faced 38 batters and allowed five singles, two walks and a hit batter. He wasn’t classically dominant — just two strikeouts — but it didn’t matter. Whatever Bochy needed, Affeldt gave him, including the win in Game 7 of the World Series.

It’s funny: Affeldt started his postseason career by giving up a home run to the first batter he faced, Ryan Howard, in 2007. He faced 110 more batters in the postseason and never allowed another extra-base hit.

Honorable mentions: Damaso Marte, Andrew Miller

Right-handed setup man: Wade Davis

Once upon a time, Davis made his postseason debut as a starter. Facing elimination on the road for the 2010 Tampa Bay Rays, Davis worked five innings to beat Texas, allowing three earned runs.

That was solid, but the bullpen was where Davis belonged. In his next 22 postseason games, one for the Rays and the rest for the Kansas City Royals, Davis worked 27 1/3 innings and allowed exactly one earned run. He struck out 39, walked six, won three games, saved four more and struck out the final batter to clinch the World Series at Citi Field in 2015.

Davis was the Royals’ closer by then, and he earned four more saves for the Cubs in 2017. But he makes the team as our right-handed setup man for showing the industry just how critical that role can be in the postseason.

In 2014, Davis appeared in all eight games of the American League playoffs as the Royals swept their way to the pennant. He was automatic, collecting every eighth-inning out (and then some) in those games, part of a sturdy bridge from Kelvin Herrera to Greg Holland that nearly guided the Royals to the title. When they got there the next year, Davis was flawless as the closer.

Honorable mentions: Bryan Abreu, Francisco Rodríguez

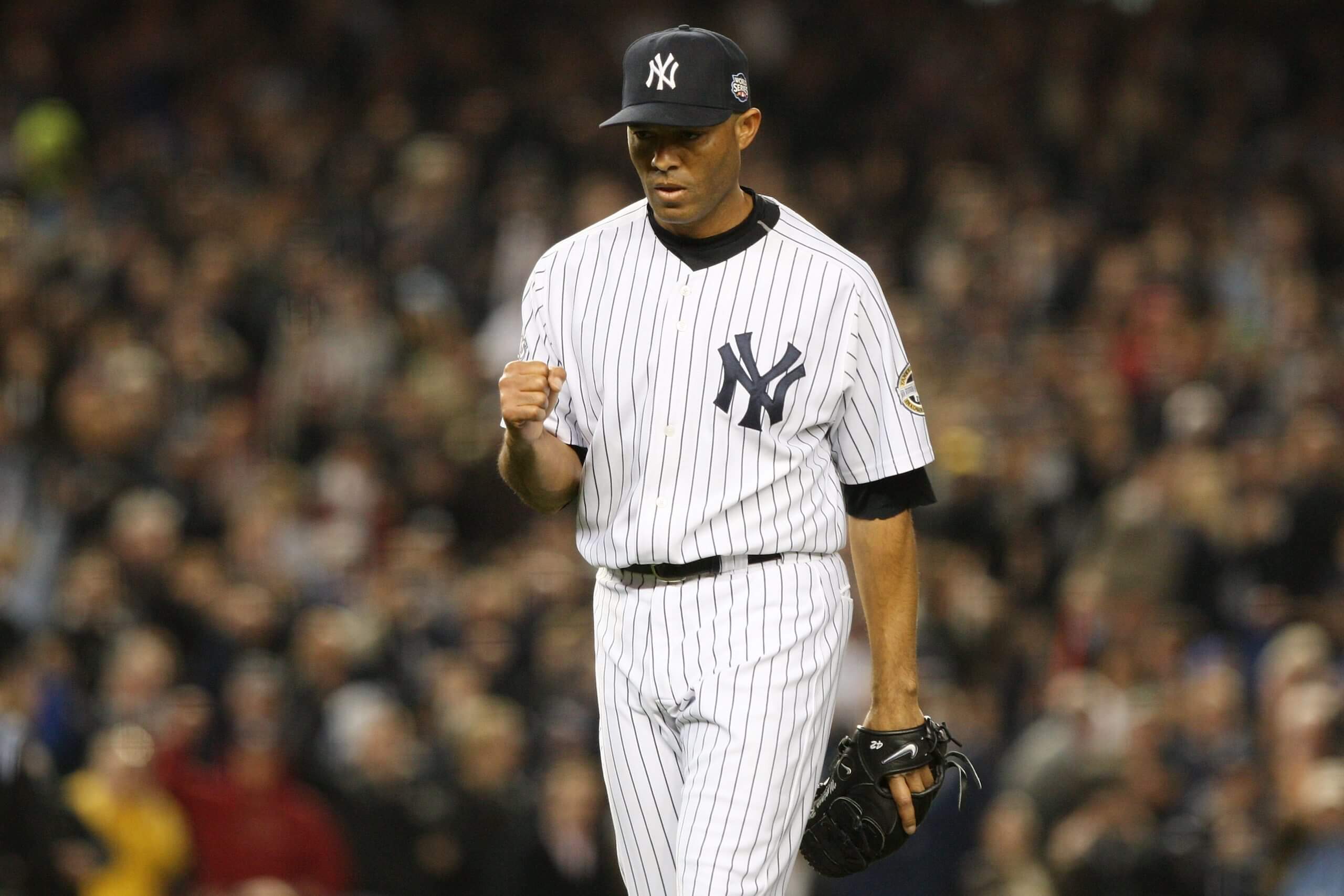

Closer: Mariano Rivera

Mariano Rivera had a 0.86 ERA in 65 postseason games in the 2000s. (Jed Jacobsohn / Getty Images)

You have to be pretty remarkable to blow the save in Game 7 of a World Series and still be hailed, universally, as the greatest postseason closer in baseball history. But that’s Mariano Rivera. He was so outrageously successful, he gets a pass for the final inning in Arizona in 2001.

Remember, we’re not even counting the 31 postseason games Rivera worked in the 1990s. Back then, he had 13 saves in 14 chances with a 0.38 ERA. He earned three rings and twice notched the final out of the season.

In the 2000s, it was more of the same. In 65 games — a typical season-long workload for a reliever — Rivera posted a 0.86 ERA, allowing one home run (to Jay Payton) that didn’t even impact the outcome of the game. He was MVP of the 2003 ALCS, rushing from the dugout to the mound and collapsing in joyous exhaustion as Aaron Boone rounded the bases to clinch in Game 7.

What made Rivera so extraordinary, though, was his ability to pitch multiple innings. Again, forget everything he did in the 1990s. In the 2000s alone, Rivera had 21 postseason saves of more than one inning. That is more postseason saves, of any kind, than any other pitcher has ever had. (Kenley Jansen is second on the career list, with 20.)

In all, Rivera collected an appropriate 42 saves in the postseason. Yes, he stumbled in Arizona and again in Boston in the fateful 2004 ALCS. Yet Rivera’s greatness made those comebacks even more significant for his opponents — and his grace in both victory and defeat make him the template for dignity and dominance.

(Illustration: Demetrius Robinson/ The Athletic. Top photos: Jeff Zelevansky, Elsa, Patrick Smith, Sean M. Haffey, Christian Petersen / Getty Images)