TARRYTOWN, N.Y. — Every summer for the last decade, Mike Sullivan and his coaching staff have scoured video of teams around the NHL before gathering to share their observations. This year, his first as head coach of the New York Rangers, the group’s prevailing takeaways reflected a league-wide trend.

“As coaches, we’re always trying to stay on the cutting edge, or on the frontier of that evolution and where that game is going,” Sullivan said. “And in my estimation, in the last 10-plus years, the game has really evolved into very much a puck-pursuit game.”

Sullivan pointed to the Carolina Hurricanes and the two-time defending-champion Florida Panthers as shining examples, noting that “some of the best teams in the league have the highest dump-in rates.” More and more coaches are willing to chip pucks behind the defense and let their players chase it, using speed and tenacity to apply pressure and win possession back deep in opposing territory.

The 57-year-old Sullivan — a two-time Stanley Cup winner with the Pittsburgh Penguins, and Team USA’s head coach for the upcoming 2026 Winter Olympics — has taken many of those elements and woven them into his own system, which brings to New York with the hope of reviving the Rangers following a calamitous 2024-25 season.

A pillar of that system will be a swarming forecheck modeled after some of the NHL’s best puck-pursuit teams, with nuances that require every skater to read and react on the fly. But Sullivan also recognizes that the Rangers’ top players — the likes of Adam Fox, Artemi Panarin and Mika Zibanejad — won’t benefit from battling for possession all game. The puck needs to be on their stick as much as possible, with the new coach’s philosophies aimed at creating more opportunities to play fast, attack in transition and generate extra possessions.

“The identity that we’re trying to build here is a little bit of a hybrid game,” Sullivan explained. “We want to keep the puck. When we have it, we’ve got some talented guys. We don’t want to just turn into a dump-and-chase or a chip-and-chase team by any stretch. We want to keep the puck as often as we can, but we also have to be willing to put pucks behind people. We’ve got to be willing to make a high flip once in a while and chase a puck down.

“And I think if we do that, we’ll have the ability to create offense in different ways.”

A forecheck built on ‘cooperative pressure’

While reviewing tape in recent years, one particular play has caught Sullivan’s attention: the “high flip,” where a player flicks the puck up and over oncoming defenders to create a race for possession behind the opponent’s net.

“That didn’t exist 20 years ago,” Sullivan said. “If it did, it was an exception, not the rule. We call it a punt, to steal a football term. That’s a common play in today’s game, whether it be off a defensive-zone faceoff, or teams ‘punt and hunt,’ where they make a high flip, it bounces somewhere, and there’s a speed game pursuing it.”

Once the pursuit begins, Sullivan will deploy the Rangers in a 1-2-2 forechecking system, with a few wrinkles. He wants the lead forward — commonly referred to as “F1” — chasing the loose puck and hounding the nearest opposing player, a standard practice league-wide. But cohesive support behind the F1 is equally important.

“A foundational aspect of that is predictability, and what I mean by that is all five guys on the ice know what their jobs are,” Sullivan said. “I’ve always said to players that isolated pressure is a lot easier to beat than cooperative pressure.”

That cooperation starts with a second layer of pressure that requires the other two forwards to take away passing options and fill gaps. If the puck carrier advances past the F1, the next-closest man should go on the attack and reapply direct pressure. And if the F1 keeps the puck carrier in check, then the next two forwards are charged with blanketing the nearest man in an effort to intercept the pass, deflect it, or force it elsewhere entirely.

“It’s kind of just one man in, one man out,” said veteran forward Conor Sheary, who’s competing for a roster spot with the Rangers on a professional tryout agreement but spent parts of four seasons with Sullivan in Pittsburgh, including both Cup runs. “In a sense, it’s man-on-man. You go after your guy, but you’re always having someone cover for you. So, once the puck moves, you’re staying above the puck. You never want to give up odd-man rushes, so you always have people reloading, especially the forwards.

“It’s about backing each other up and just trying to stay above the play.”

The third layer comes in the form of the two defensemen. They, too, are asked to press forward when needed, but they’ll often be positioned along opposite walls. The pressure from the three forwards is designed to funnel opponents to the outside, where the defensemen should be waiting to pinch down, disrupt the play and, hopefully, flip possession.

“There’s certain reads that they’ve instilled into our forecheck,” Sheary said. “There’s only so many things (the opposing team can do). They can go weak side, strong side or up the middle, essentially. So, within all those breakouts, I think we have something to counteract that and read off that.”

It’s a significant change from the 1-3-1 forecheck the Rangers ran under previous coach Peter Laviolette. That system also required the F1 to aggressively pursue the puck, but it left him on an island. The other two forwards, plus one defenseman, were charged with sitting back to create a neutral-zone trap. The Rangers had some early success using it to clog the middle of the ice, but too often got caught flat-footed and were left vulnerable to odd-man rushes.

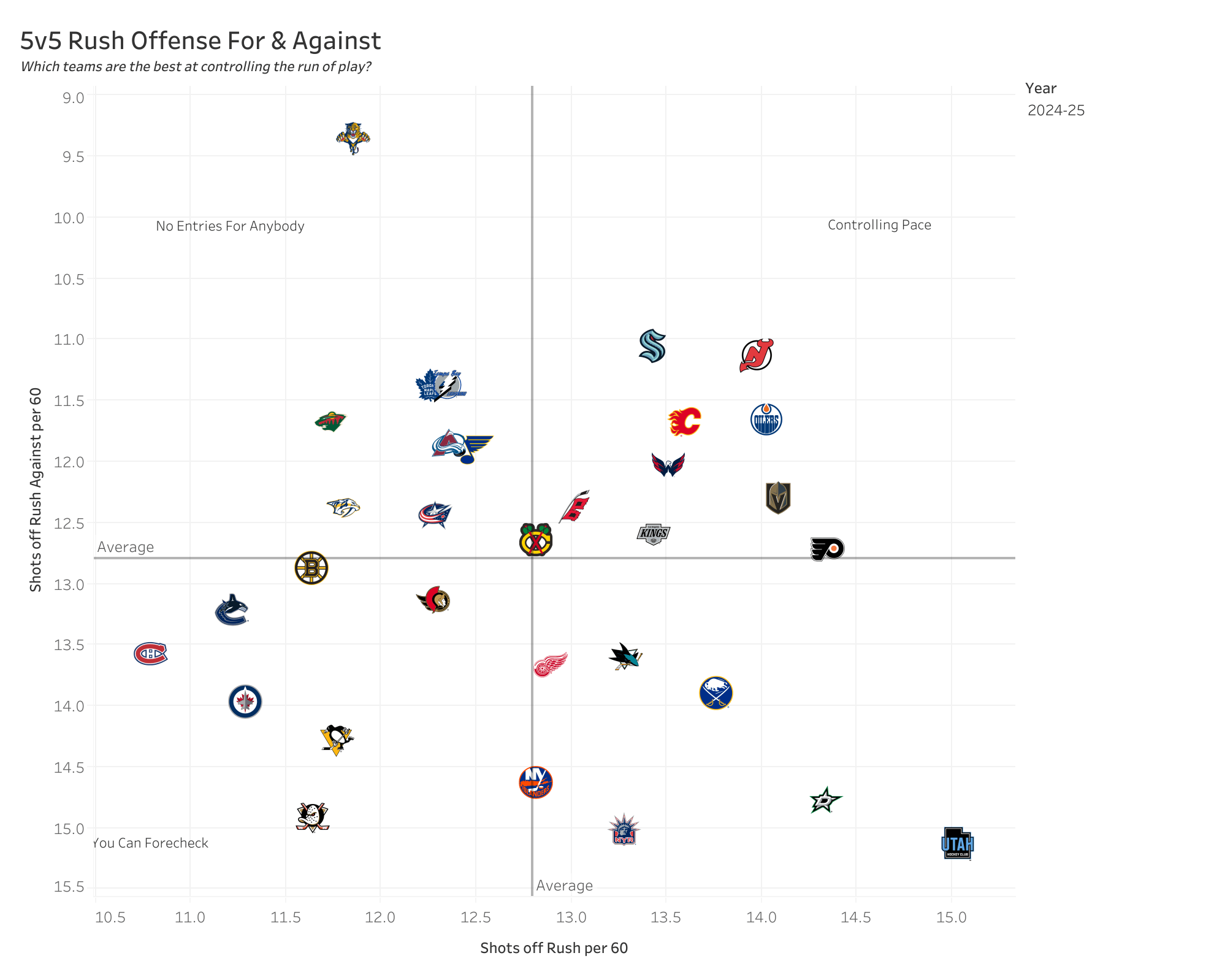

The result was an average of 15 shots allowed off the rush per 60 minutes at five-on-five, according to Evolving Hockey, which ranked 31st out of 32 teams.

“Most teams are going to break out against one forechecker,” Zibanejad said. “So now, all of a sudden, you’re facing them coming up ice as you’re coming up ice. They’re basically coming right at you with possession and control. It’s hard.”

In Sullivan’s system, the Rangers plan to be the aggressors. They want to force opponents into mistakes — a situation they’ve found themselves on the wrong side of far too often in recent seasons — and to generate quick-strike scoring chances in return.

“On the surface, it might suggest that, ‘Hey, if we’re going to be aggressive up the ice with a puck-pursuit game and a forecheck, there might be risk involved.’ And potentially there is,” Sullivan said. “But the way that I look at it, there’s also risk involved and in just retreating and playing on your heels and letting your opponent dictate the terms and spending more time in your end zone. When you think about team defense, it can take place different ways. It doesn’t necessarily just mean in your own end.

“I think the best teams, their team defense starts in the offensive zone with their puck-pursuit game and their forecheck. They play on top of you. They make it harder for you to earn ice.”

D-zone coverage better suited for personnel

Not only did the Rangers struggle to muster a consistent forecheck and slow opponents down in transition last season, but they were just as bad in their own end.

In 2024-25, New York ranked 28th in the NHL with 2.76 expected goals-against per 60 and 29th with 12.2 high-danger scoring chances allowed per 60, according to Natural Stat Trick.

Those poor numbers speak to issues protecting prime defensive-zone real estate, such as the net-front and slot areas. It’s been a problem for years, and while world-class goalie Igor Shesterkin was able to mask it for a while, the dam finally broke.

Roster construction is certainly part of the problem, with a group of forwards that lacks plus defenders and a core of defensemen short on quality depth behind Fox. But those issues were exacerbated by Laviolette’s man-on-man coverage. He simply didn’t have the chess pieces to chase opponents all over the ice without losing a step or getting lost in traffic, resulting in a seemingly endless string of breakdowns and confusion.

“I don’t know what the numbers were the first year (under Laviolette in 2023-24) when we made it to the conference finals, but I feel like we still had a lot of those games where we gave up a lot (of high-danger scoring chances),” Zibanejad said. “You see that when you’re playing against man-on-man and someone loses an edge, or someone gets beat, it’s open. Now, all of a sudden, you’re scrambling because you don’t know who’s going to cover who. Because if I’ve got to cover for the guy who fell, or I’ve got to cover for the guy who got beat, I’ve got to leave my guy. But who’s taking my guy now?”

Under Sullivan, New York will switch to a zone defense in its end. Zibanejad acknowledged the potential for leaks in the new scheme, as well, noting some of the ways the Rangers have used passing plays to uncover weak spots against opponents who play zone. But most players believe the benefits will outweigh those negatives.

“It’s not like a man-on-man system, where you’re just chasing your guy the entire shift,” center Vincent Trocheck said. “A lot of times, whenever you are doing that, it does take away energy from your offense. Any time you do turn the puck over, you might not have the legs to get to offense. Whereas in this system, it’s more reading and reacting.”

Trocheck explained that “everybody has a quadrant” within the structure of the zone. The two wingers cover the top halves of each circle up to the blue line, while defensemen section off their own areas down low on either side of the net. The center is left to roam, support, and hunt for takeaways.

“The center’s kind of in the middle of the ice, but this (system), it gives them a little bit less space, where the wingers are still able to cut off the top,” Trocheck said. “They’re able to cut off that pass from low to high to the D. And then if there is a breakdown, there’s situations where you have to read and react, and the center is kind of the guy who is in the middle of the ice reading everything. If there is an opportunity to jump on a puck, you go.”

To make it work, Sullivan stressed the importance of having all five skaters on the same page. Whether discussing the forecheck, breakouts or D-zone coverage — all areas where the Rangers must improve if they plan to bounce back this season — the coach always brings it back to “predictability.”

“Conviction” is another key word. Sullivan and his assistants in New York spent all those hours watching film to draw inspiration from the successful coaches around the league and determine the best path for their new team. There are reasons to feel optimistic about the system they’re bringing, but their biggest challenge, as it was for their predecessors — including former head coach and current Sullivan assistant David Quinn — will be making sure the Rangers execute it consistently.

“My feeling on man-on-man vs. zone defense is, it all depends on what your personnel group is,” Sullivan said. “We looked at all the elements of the game and try to pick our own game apart. Figure out what we think is in the best interest of the Rangers, and then we make decisions from there. I think there are pros and cons to any system that you implement. I think they’re all effective when executed properly.

“It’s a matter of selling a certain message as a coaching staff, teaching it the right way, and then buying in — commitment to play in the game a certain way. And the onus there falls on me as the coach.”

(Photo: Bruce Bennett / Getty Images)