Micronutrients are minerals and vitamins that our body requires in specific concentrations to support healthy physiological function.

Because many micronutrients must be obtained through diet, deficiencies can be common and disproportionately affect low- and middle-income countries.

Prolonged, severe deficiencies can exert selective pressure on human genes.

Dr. Jasmin Rees and colleagues at University College London (UCL) recently conducted a study to explore the extent of this influence and examine how micronutrients collectively have helped shape human evolution. The research is published in The American Journal of Human Genetics.

“We ran comprehensive simulations to evaluate which currently published methods had the highest power to identify positive selection acting 1) on individual genes and 2) across gene sets,” Rees, who led the research while completing her PhD at UCL, told Technology Networks. She is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Pennsylvania.

“From these simulations, we selected the two methods with the highest power to use in our study: one that identifies regions of the genome that are unusually differentiated between two populations (as expected under local adaptation i.e., adaptation in only some populations), and one that reconstructs the history of individual variants across the genome to identify those that appear to have increased in frequency at an unusually rapid pace (as expected under positive selection),” Rees added.

What is positive selection?

Positive selection refers to a process where versions of a gene are favored by natural selection because they increase the fitness of an organism.

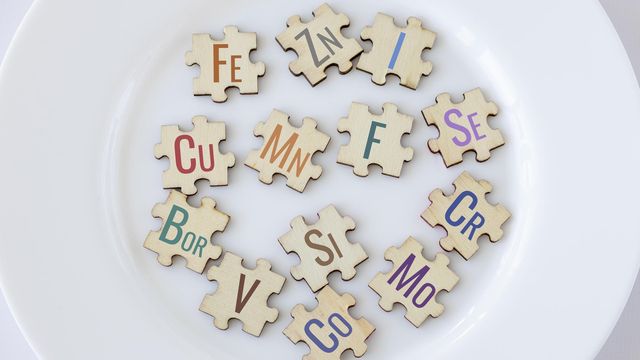

These methods were used to analyze 276 genes associated with 13 essential minerals, including selenium, copper, iron, magnesium, zinc, sodium, calcium, iodine, chloride, potassium, phosphorus, manganese and molybdenum, from existing datasets.

“We focused on 13 essential minerals due to their relevance in public health and the available literature surrounding the genetic basis of their uptake, regulation and metabolism,” Rees explained.

Most of the genes assessed in this study have a range of biological functions – it’s possible that selection could act on a function that is not related to micronutrients. To account for this limitation as much as possible, the team focused on identifying signatures of positive selection on gene sets where all genes were associated with the same micronutrient.

“When there are signatures throughout a gene set where all genes have a shared function, this is a stronger argument for positive selection on that function (in this case, their role in micronutrient uptake, metabolism or regulation),” Reese explained.

Shorter height may be an adaptation to low iodine

The researchers found evidence for adaptation associated with each of the 13 minerals studied in at least one population.

“This suggests that micronutrients have been a powerful and widespread selective force throughout human history,” said Rees.

“In Central America, the Maya – who live in regions with iodine-poor soils – show strong evidence of genetic changes in genes indicated in iodine regulation or metabolism, which could reflect adaptation to low levels of iodine in the diet,” Rees said.

“Similarly, we found that the Mbuti population of Central Africa – another population noted for their short stature and living in environments with iodine-poor soils – also bears signs of genetic adaptation in some of the same iodine-dependent thyroid receptors. Given that, in this same region of Central Africa, another short-statured population has previously been shown to have lower rates of goiter than their taller neighbors, we speculate that shorter stature may be linked to an evolutionary adaptation to the risks of low iodine.”

Rees emphasized her use of the word “speculate” when describing these results as, without comprehensive environmental data, the researchers cannot formally test an association between micronutrient content of local soils and the identified signatures of positive selection.

Two genes related to magnesium, FXYD2 and MECOM, also showed signs of adaptation in Central-South Asian groups, where the soil can be very rich in magnesium. As FXYD2 and MECOM have been associated with hypomagnesemia, these genetic changes may have helped people avoid health problems from magnesium toxicity – possibly by lowering magnesium absorption.

Could local genetic adaptation shape population differences in micronutrient deficiency?

Collectively, the study’s findings suggest micronutrients have likely driven genetic adaptation across a range of populations and environments.

Rees and colleagues hope the study insights are of interest to researchers in the fields of human population genetics, evolutionary biology and evolutionary medicine, and will prompt further study: “Comprehensive characterization of soil environments would help understand the proposed associations between soil environments and the observed genetic signatures,” she said. “Functional analysis of genes of interest would also aid in understanding their exact role and the biological mechanisms surrounding micronutrient uptake, regulation and metabolism,” she continued.

Large biobank and public health data could also reveal population differences in micronutrient deficiency and toxicity that are potentially shaped by a history of local genetic adaptation.

Reference: Rees J, Castellano S, Andrés AM. Global impact of micronutrients in modern human evolution. Am J Hum Genet. 2025. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2025.08.005

About the interviewee

Credit: Jasmin Rees.

Dr. Jasmin (Jas) Rees is a researcher in population genetics, with a specific focus on human evolution and adaptation. She is especially interested in the role that the environment can play in driving local adaptation of populations, particularly when this exposes contemporary populations to differential health risks. The work described here was completed during her PhD at University College London, where she has since graduated. She currently works at the University of Pennsylvania in the Tishkoff Lab as a postdoctoral researcher, leveraging a range of computational methods to understand genetic adaptation and past demography in ethnically diverse African populations. She loves cooking, running and her puppy Rango Bango.