Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

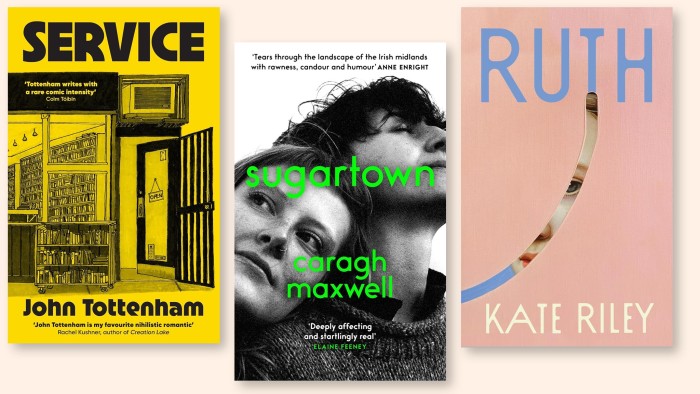

Situations that would be tragic in life become delightful when burnished by a fine prose style. John Tottenham magically transmutes existential despair, romantic disappointment, ageing, drug use and a despised day job into high comedy in Service (Semiotext(e) $17.99/in the UK from November 6, Tuskar Rock £14.99).

Terminally weary Sean, late forties, is trying to write a novel (this novel, in fact), while working shifts in a bookshop in a rapidly gentrifying area of Los Angeles. The sudden influx of hip youth into a working-class neighbourhood is just one of the things Sean cannot abide, as cheap, authentic bars and eateries close and reopen as gaudy, overpriced facsimiles of their former selves.

Toting their phones, the giddy incomers tumble into his store, the perfect backdrop for their social media posts. Some of them even want books, but Sean quickly discourages that. Pages and pages detail his inability to invent characters or settings, so his masterwork will have to be a novel about a man who works in an LA bookstore who’s trying to write a novel.

A critical local barista offers suggestions Sean struggles to incorporate, such as creating a convincing female character or a sex scene. As the demands of his clientele escalate (Do you have a washroom? Where can I find Kafka? Do you have The Artist’s Way?), Sean is heading for a spectacular crack-up. Service manages to be savage, furious, hilarious and melancholic all at once.

New Yorker Avery may be at the other end of the age spectrum and the country but she is equally adrift in the modern world, and also trying vainly to write. Anika Jade Levy’s Flat Earth (Abacus £14.99/Catapult $26) exudes ennui and sadness, each chapter prefaced by a mordant precis of bizarre fads and news stories to set against its heroine’s apathy and dysfunction.

Fingers constantly bleeding from the smashed glass of her cell phone, Avery is addicted to men who abuse her, sometimes for money; one has carved his initials into her breast. Her much more successful, happy and rich friend Frances is making a film called Flat Earth, about the overlooked and disgruntled (and Trump-voting) across America; Avery joins her listlessly for part of the road trip. There is a glum kind of humour woven into the despair, and the hopelessness is rendered strangely hypnotic in crisp, pitiless prose.

Caragh Maxwell’s Sugartown (Oneworld £12.99) evokes sadness and introspection by way of a garrulous and buttonholing style. Saoirse has returned from London to her roots, “one big soul-sucking plughole of a town” in Ireland, fleeing a failed relationship. This has entailed moving back in with Máire, her opinionated mother, and younger siblings, and taking on an undemanding job in a hardware store in the post-Celtic Tiger economic doldrums. Her only outlet is self-defeating: drug and alcoholic binges with equally low-achieving friends. Maxwell’s lush descriptions of partying surge with underlying angst, yet the attendant misery is always undercut with a wry cynicism: “The overarching theme of the Annual Irish Suffering Olympics was ‘get over yourself, there’s worse off than you’.”

Saoirse also has a more successful best friend, the confident Doireann. A new acquaintance, Charlie, brings the promise of romance, but Saoirse’s demons constantly threaten to resurface and trample the fragments of a life she’s attempting to put together. Thrilling with the fullness of even painful emotion, in Sugartown uncertainty, awkwardness and guilt have never sounded so appealing.

The lead character of Ruth by Kate Riley (Doubleday £16.99/Riverhead $29) suffers from a surfeit of meaning and direction in her life; she is born into an Anabaptist sect of Christian communists, where all property is shared and individuality is frowned upon. Ruth soon learns to tame her natural rebelliousness, which however breaks out in a subversive wit on occasion. As expected, she marries a man she barely knows, who unlovably addresses her as “Mom” from day one.

At this point most readers would expect a lurid tale of abuse and religious hypocrisy, but the sect is more supportive than oppressive. Ruth is a touching tale of a radical experiment in living which, while it limits individual expression and agency, nevertheless offers much that is comforting in return. Riley’s deft prose has surprising angles and hidden spikes.

Recommended

A paean to ancient hostelries and oral storytelling, Sam Reid’s The Pin Jar (Rough Trade £13.99) pulls the reader deep into the past with its three folk tales from the Sussex Weald, compiled, in the framing device, by an amateur ethnographer and composer who tapes stories and songs he hears from local eccentrics in pubs. Told in dialect and set out as poetry, the title story refers to a method of repelling witches, “Takener” concerns a malevolent nature spirit awoken when a wood is felled for money, and “A Hand in Your Own Undoing” tells of the murder of a local beauty and its dire aftermath. Mine’s a pint!

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X