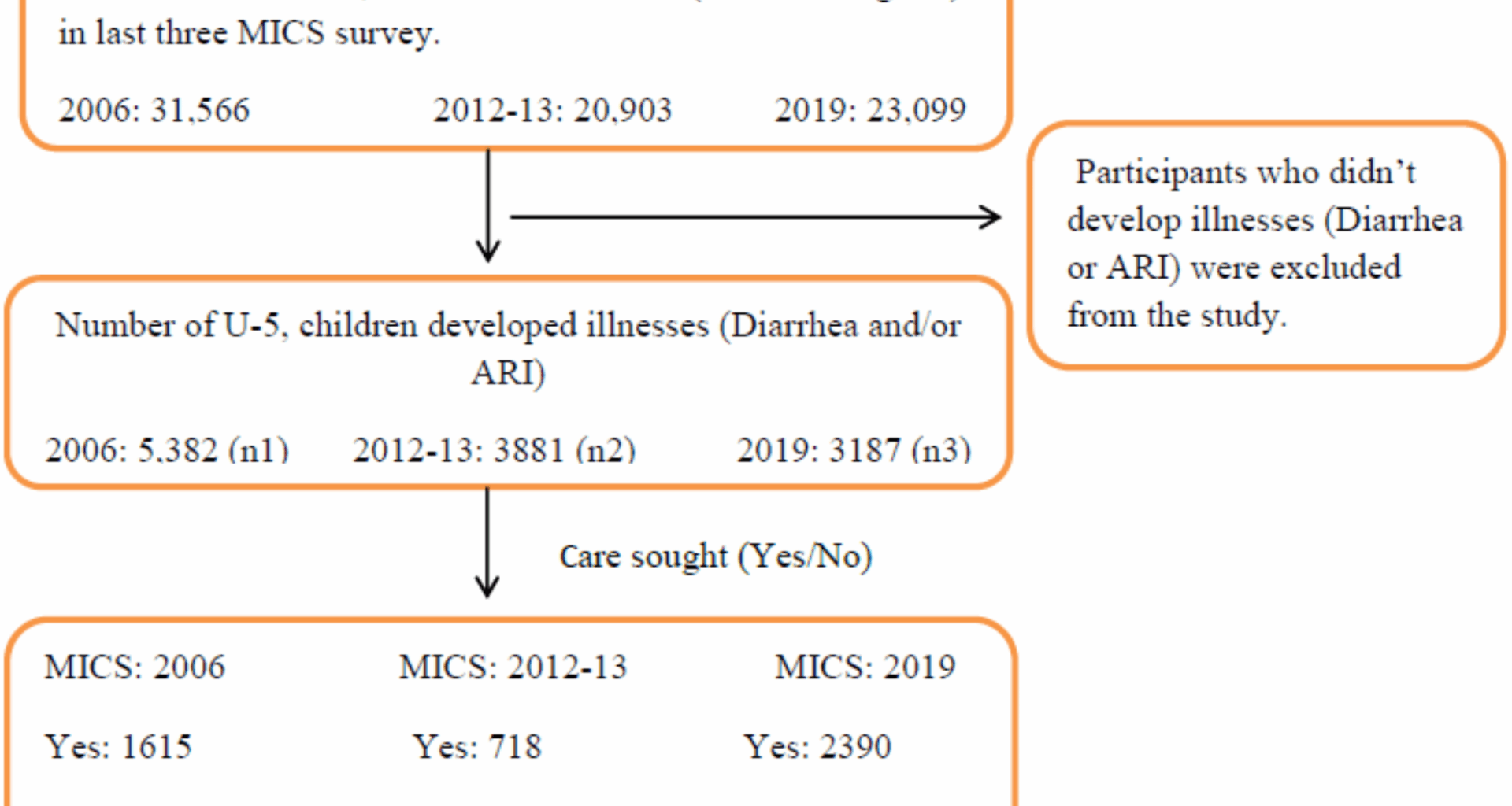

Prevalence and trend for care seeking of childhood illnesses

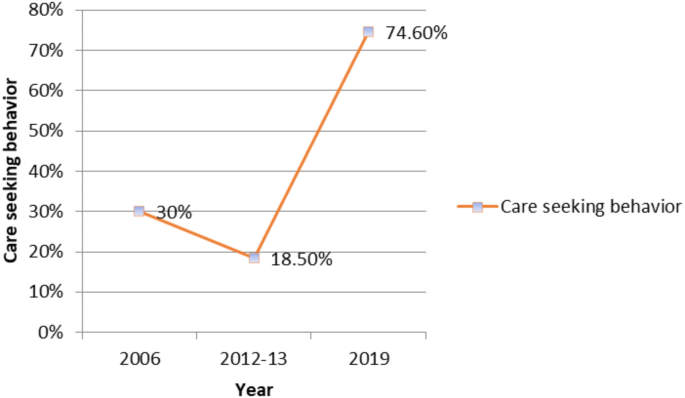

In this study, 17.1% (5,382) of children under five years of age developed illnesses in 2006, yet only 30% (1,615) sought medical care. During the period–2012–2013, 18.6% (3,881) of the children experienced illnesses, but care was sought for only 18.5% (718). By 2019, 13.8% (3,187) of children had developed illnesses, and medical care was sought in 74.6% (2,390) of those cases (refer to Fig. 1). The data indicated a significant decline in care-seeking behavior from 2006 to 2012–2013, dropping from 30 to 18.5%. However, there was a remarkable recovery in 2019, with an increase of approximately 56%, from 18.5 to 74.6%. This reveals a distinct upward trend in care-seeking behavior over time (see Fig. 2).

Care-seeking behavior trend

Bivariate analysis

The association between care-seeking behavior for childhood illnesses and gender was insignificant in 2006 (p = 0.124), suggesting that care was sought similarly for both male and female children. However, this changed in subsequent years, with a significant association emerging in 2012-13 (p < 0.05) and in 2019 (p < 0.05), when more care was sought for male children than for female children (Table 1). This gender disparity highlights the growing trend of prioritizing male children in healthcare-seeking practices over time. A statistically significant association between area of residence and care-seeking behavior was observed in 2006 and 2012-13 (p < 0.05), indicating that the likelihood of seeking care for a child’s illness varied significantly depending on where the child lived. Interestingly, this association was insignificant in 2019, potentially reflecting the changes in healthcare access or awareness across different regions. The division displayed a highly significant association with care-seeking behavior across all three study periods (p < 0.001), emphasizing substantial regional differences in healthcare-seeking practices. The highest rate of care-seeking was observed in Rajshahi division (35.3%) in 2006, Sylhet (32.5%) in 2012-13, and Rangpur (84.7%) in 2019, reflecting regional variations in healthcare access and utilization. Notably, compared to 2006, care-seeking behaviors declined in every division in 2012-13 but increased significantly in 2019, indicating a possible improvement in healthcare awareness or access in recent years.

A significant association was observed between care-seeking behavior and the age of the children across all three study periods (p < 0.001, p < 0.05, and p < 0.05). In 2006 and 2012-13, the highest percentage of care-seeking was observed for children aged 0–11 months (35.3% and 22.7%, respectively), reflecting a more significant concern for infant health. However, in 2019, the greatest care-seeking was for children aged 48–59 months (79.8%), suggesting a shift in focus toward older children, perhaps due to the increased awareness of the health needs of this age group. Across all age groups, the utilization of care services decreased in 2012-13 compared to 2006, but remained high in 2019, indicating an overall improvement in healthcare utilization over time. Significant associations between maternal education and care seeking were observed in 2006 and 2012-13 (p = 0.012 and p = 0.007, respectively), but this association was no longer significant in 2019 (p = 0.271). This change may reflect broader healthcare access improvements that reduce the relative influence of maternal education on care-seeking. By contrast, the relationship between care-seeking behavior and the educational status of the household head, which was not significant in 2006 and 2012-13, became significant in 2019 (p = 0.022). In 2019, the highest level of care was sought for children in households where the head had secondary education (approximately 78%), followed by those with higher education (75%), primary education (74%), and no education (72%). This trend suggests that education level increasingly influences healthcare-seeking behavior, possibly due to better health knowledge or improved financial status of households. The association between religion and care-seeking behavior was significant in 2006 (p < 0.10), indicating that religious beliefs may influence healthcare decisions. However, this association was insignificant in 2012-13 and 2019, suggesting that the influence of religion on care-seeking behavior diminished over time. Similarly, the association between ethnicity and care-seeking behavior, which was insignificant in 2006 (p = 0.157), became highly significant in 2012-13 and 2019 (p < 0.001). This shift highlights the growing disparities in healthcare access and utilization between different ethnic groups, with Bengali participants consistently seeking more healthcare than participants from other ethnic groups. This disparity may reflect broader social and economic inequalities that persist despite overall improvements in access to healthcare.

Throughout the study period, the association between children’s breastfeeding status and care-seeking behavior was insignificant in 2006 (p = 0.646) and 2012-13 (p = 0.327). However, this relationship became significant in 2019 (p = 0.005), suggesting that breastfeeding status started to play a critical role in whether care was sought at that time. Similarly, there was no significant relationship between wealth quintiles and care-seeking behavior in 2006 (p = 0.679) and 2019 (p = 0.192); however, a significant relationship emerged between 2012 and 13 (p < 0.10), indicating that socioeconomic factors briefly influenced care-seeking behavior during that period. The association between care-seeking and the total number of under-5 children in the household was significant in 2006 (p < 0.10) and 2012-13 (p < 0.10), implying that households with more young children were more likely to seek care during those years. However, this association became insignificant in 2019, possibly because of improved access to healthcare or changes in family dynamics. In both 2006 and 2012-13, there was a significant association between care-seeking behavior and the availability of handwashing facilities (p < 0.05), indicating that better hygiene practices may be linked to higher care-seeking rates. By 2019, this association was no longer significant (p = 0.136), reflecting broader improvements in hygiene and health awareness. Although care-seeking rates significantly increased in 2019 compared to 2012-13 for both stunted and non-stunted children, the association between childhood stunting and care-seeking behavior was insignificant 2019 (p = 0.541).

Table 1 Prevalence and association of care-seeking behavior for childhood illnesses according to selected covariatesMultivariate analysisDeterminants of care-seeking behavior of childhood illnesses

In 2006, female children were nearly 10% less likely to seek care than their male counterparts were (AOR = 0.902, 95% CI: 0.801–1.015, p < 0.10). This gender disparity in care-seeking behaviors persisted and intensified over time. By 2012-13, the likelihood of care seeking among female children was almost 20% lower (AOR = 0.808, 95% CI: 0.684–0.954, p < 0.05), and in 2019, it remained approximately 15% lower (AOR = 0.850, 95% CI: 0.684–0.954, p < 0.10). These results demonstrate a consistent trend of lower care-seeking behavior among female children compared to their male peers (Table 2). In 2006, care-seeking behavior was notably higher in the Barisal, Khulna, Rajshahi, and Sylhet divisions than in the Dhaka division (p < 0.05, p < 0.001). This indicates that these regions had more accessible or better-utilized healthcare services during that time. By 2012-13, the Chittagong division demonstrated a significantly lower rate of care-seeking behavior, while the Sylhet division exhibited significantly higher care-seeking rates. The remaining divisions showed no significant differences in care-seeking behavior compared with Dhaka, reflecting a shift in the regional dynamics of healthcare.

By 2019, care-seeking behavior had varied considerably across the divisions. The likelihood of seeking care was significantly higher in the Chittagong division (AOR = 1.685, 95% CI: 1.272–2.232, p < 0.001), Khulna division (AOR = 1.482, 95% CI: 1.094–2.007, p < 0.05), Rajshahi division (AOR = 1.480, 95% CI: 1.071–2.045, p < 0.05), Rangpur division (AOR = 2.723, 95% CI: 1.872–3.961, p < 0.001), and Mymensingh division (AOR = 2.308; 95% CI: 1.579–3.372, p < 0.001), indicating substantial regional disparities in healthcare utilization. In contrast, the odds of seeking care were lowest in the Sylhet division (AOR = 0.466, 95% CI: 0.311–0.698, p < 0.001) when compared to Dhaka, highlighting the significant regional variation in care-seeking behavior. The results for the Barisal division were insignificant, suggesting no notable difference in care-seeking behavior from that of Dhaka.

In 2006 and 2012-13, the likelihood of seeking care was significantly lower for children in all age groups than for those aged 0–11 months. However, by 2019, this pattern had shifted, with children aged 12–23 months exhibiting a significantly lower likelihood of seeking care compared to those aged 0–11 months (AOR = 0.787, 95% CI: 0.627–0.988, p < 0.05), while other age categories showed no significant differences. Regarding maternal education, there were no significant differences in care-seeking behavior among various educational groups compared to the ‘None’ category in 2006. However, in 2012-13, care-seeking was significantly higher for mothers with primary and secondary education. By 2019, women with primary education had 20% higher odds of seeking care than those without education (AOR = 1.20, 95% CI: 0.887–1.622, p < 0.05), indicating that improved care-seeking behavior is linked to maternal education. No significant differences were observed in care-seeking behavior across educational groups in 2006 and 2012-13 for household head’s education. Nevertheless, in 2019, those with secondary education had almost 30% higher odds of seeking care than those without education (AOR = 1.296, 95% CI: 1.027–1.636, p < 0.05), whereas other education categories showed no significant associations. Ethnicity also played a role in care-seeking behavior, with significant associations observed in 2012-13 and 2019. Notably, in 2019, the odds of seeking care were nearly 82% lower for ‘Others’ compared to Bengali participants (AOR = 0.185, 95% CI: 0.097–0.353, p < 0.001), highlighting substantial disparities in healthcare access among different ethnic groups.

In 2006 and 2012-13, there were no significant differences in care-seeking behavior across the various wealth quintiles compared to the poorest quintile. However, in 2019, participants from the wealthiest quintile sought nearly 39% more care than those from the poorest quintile (OR = 1.393, 95% CI: 0.973–1.983, p < 0.05), indicating a notable increase in care seeking among wealthier households. In 2006, families with two under-5 children sought care significantly less often than those with one under-5 child (AOR = 0.824, 95% CI: 0.719–0.943, p < 0.01). Conversely, in 2012-13, care-seeking was significantly higher for families with three or more under-5 children (AOR = 1.483, 95% CI: 0.949–2.317, p < 0.10), reflecting a shift in care-seeking patterns. By 2019, this association was no longer statistically significant. The availability of hand-washing facilities and childhood stunting had significant effects solely during 2012-13. Heightened health awareness may affect care-seeking behaviors, prompting more children to seek medical attention when unwell. However, these associations were insignificant in 2019. Additionally, the area of residence, religion, and breastfeeding status of children did not show any significant association with care-seeking behavior across the three study periods, indicating that these factors had a limited impact on whether care was sought for under-5 children.

Table 2 Multivariate logistic model for association of care-seeking behavior with selected covariates