A decade after earning the Nobel Prize in chemistry, UNC School of Medicine professor Dr. Aziz Sancar shows no signs of hanging up his lab coat.

At 79, he continues to teach molecular biology to undergraduate Tar Heels, advance cancer research and invest in Carolina Turk Evi, a community center for Turkish graduate students and visiting scholars.

While some might slow down or retire altogether after achieving the most prestigious award in science, Sancar continues to devote his life to scientific discovery and help future researchers excel in their careers. Most recently, his lab discovered a new biochemical approach to treat brain tumors.

Sancar’s discovery caused a ripple effect in numerous scientific fields, answering many questions related to DNA damage. (Johnny Andrews/UNC-Chapel Hill)

Winning the Nobel

Along with researchers Tomas Lindahl and Paul Modrich, Sancar received the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 2015 for his groundbreaking work on DNA repair.

His research mapped out a complex, crucial biological process called nucleotide excision repair in which proteins cut out damaged DNA segments and replace them with new ones. The revolutionary findings provided an explanation for how cells protect and repair themselves after sustaining DNA damage such as that received from ultraviolet radiation caused by exposure to sunlight.

Sancar’s discovery caused a ripple effect in numerous scientific fields, answering many questions on how DNA damage contributes to genetic mutations, cancer and neurological disorders.

DNA repair removes and corrects damage caused by chemical exposures and ultraviolet radiation. When this critical process fails, genetic mutations build up. This ultimately disrupts genes that regulate cell growth and division and drive cancer growth.

Sancar’s research has centered on uncovering the main molecules that carry out the disruption. Toward the beginning of his career, he studied photolyase, a blue-light–powered enzyme, and mapped out how it repairs UV-induced DNA damage.

“It is the most beautiful enzyme,” said Sancar. “It has such a beautiful color when you hold it against the light. I was so in love with it that I laid out its mechanisms down to the picosecond. To me, this was more exciting that my work that led to the Nobel Prize.”

At Carolina, Sancar’s lab discovered that cryptochromes — proteins related to photolyase — regulate the body’s 24-hour circadian clock, which controls sleep, hormone release, digestion and mood.

“They all link together,” said Sancar excitedly. “The bacterial DNA repair protein photolyase is related to the mammalian circadian clock protein cryptochrome. And cryptochrome regulates nucleotide excision repair.”

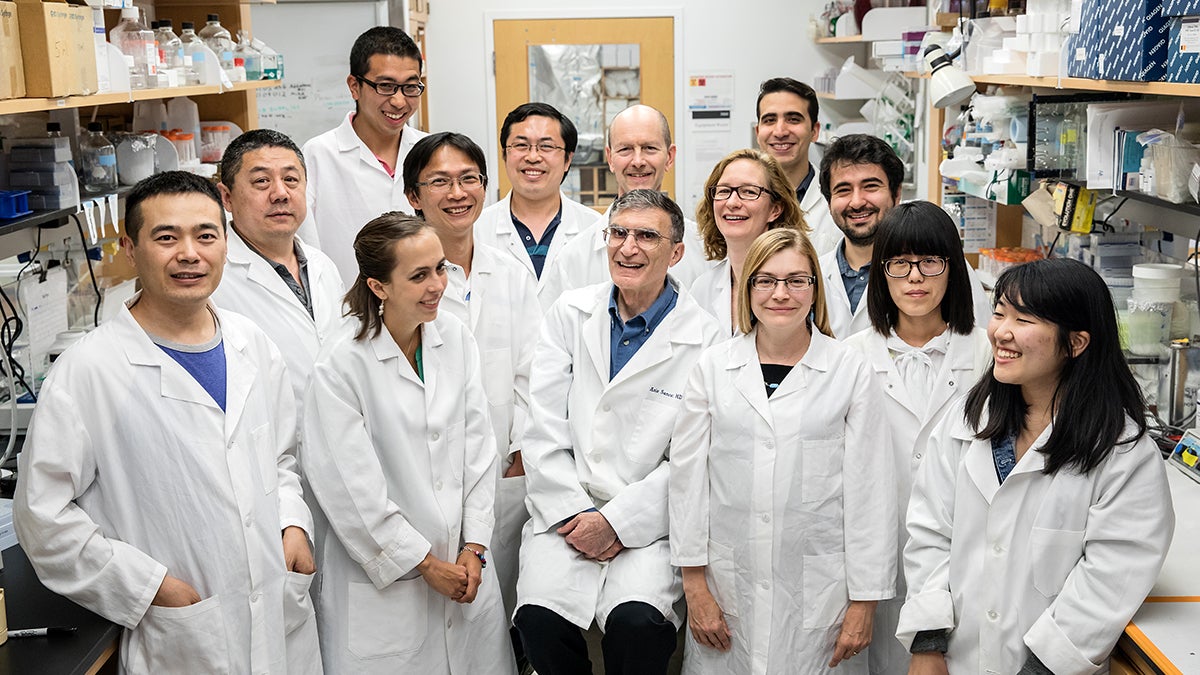

Sancar has trained more than 35 students and 55 postdocs during his time at Carolina. (Johnny Andrews/UNC-Chapel Hill)

A passion for the next generation

As one of the longest serving faculty members at the University, Sancar still gives lectures and has drawn graduate students from across the United States and around the world to study with him.

“I have trained more than 35 students and more than 55 postdocs over 40 years of being in the business,” said Sancar.

Laura Lindsey-Boltz was one of his postdoctoral trainees and a member of the Sancar lab when he won the Nobel. Now she’s now an associate professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the medical school.

“He’s provided me a lot of wisdom about which subjects are important to work on and when it is time to abandon a project and move on to something else,” said Lindsey-Boltz. “He also has this ability to see the bigger picture of what we can do to advance science.”

Sancar points to his graduate and postdoctoral trainees as the true engine of his lab. If it weren’t for Lindsey-Boltz and Christopher Selby, an adjunct instructor who helped make the initial findings on photolyase and cryptochrome, Sancar says, the lab may not be where it is today.

“They are my heroes,” said Sancar. “When I was handling Nobel press, the lab was being run by Laura and Chris, so the work could still go on. I believe it was our most productive few years after that.”

Sancar’s advice for young scientists:

“Don’t be carried away with the beauty of your work. It’s important to choose a topic that will make a difference. You should always keep in mind the impact that your work could have on society and the scientific community.”

“You have to work very hard. There is really no way around it. In science, only 20% of our experiments work. And so you have to have thick skin.”

“Keep up with what is going on in the rest of the scientific world. What made my career successful was that I would read scientific journals constantly, and I would do it the day they came out. In fact, I was ultimately able to purify large quantities of photolyase because I saw a paper in Nature about cloning genes.”

Sancar’s dedication to science and students ensures that his influence will carry forward for years to come. The Nobel laureate will continue to be a model of how one person’s passion for science and mentorship can make a real difference for humanity.