A ban on photographing and filming people without their permission appears set to be signed into law in Uzbekistan after the country’s parliament voted in favor of the legislation on October 7.

The law would require verbal or written approval from people being photographed or filmed, with fines of up to $1,364 and confiscation of camera equipment for violations. The legislation awaits Senate approval, but that step is largely viewed as ceremonial in the Central Asian country.

Anzor Bukharsky, a high-profile Uzbek photographer who leads photo expeditions for tourists, told RFE/RL that much remains unclear about how the law would be enforced and how it would apply in the case of crowds and incidental figures in a photo. “Can a citizen claim that the person in the photograph is really them if they are wearing a gas mask or Santa Claus makeup?”

School children trying on gas masks in Bukhara.

School children trying on gas masks in Bukhara.

Uzbek lawmakers have presented the ban as a way to protect people’s privacy, especially children, with a clause specifying that parents or caregivers must give permission for a child under 16 to be photographed.

Critics point to a series of scandals involving corrupt police and officials caught on camera as the potential motivator for the new law. A draft of the legislation was first proposed in 2020, which would forbid the publication of images and recordings. In the law’s current version, that has been expanded to include such recordings’ “capture and storage.”

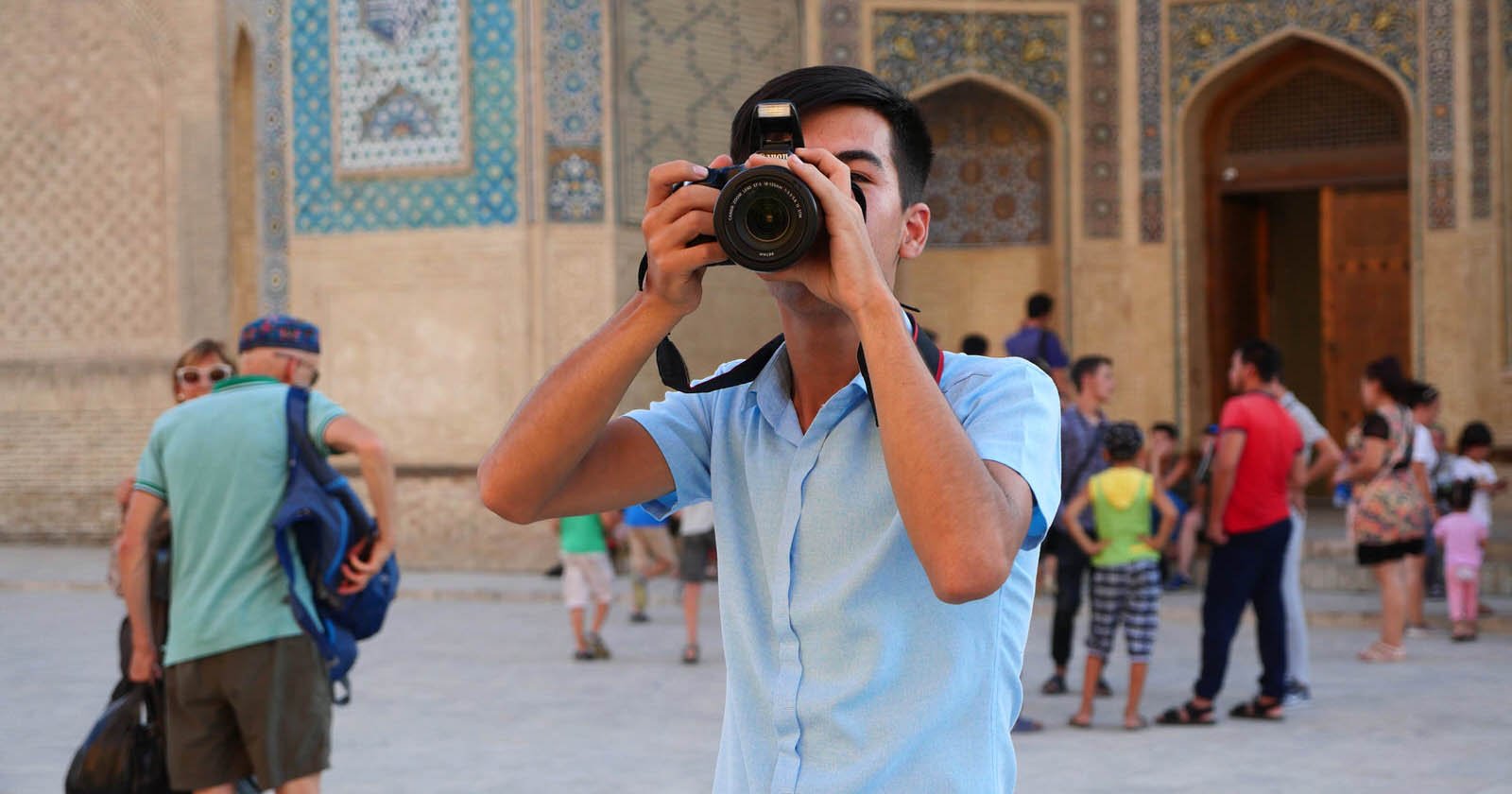

A man walking through the Registan of Samarkand.

A man walking through the Registan of Samarkand.

Uzbekistan welcomes millions of tourists each year who are drawn to its Silk Road architecture, but Bukharsky says tourists are increasingly younger and more adventurous than the elderly, package tour demographic the country attracted in its early decades of independence.

“These younger tourists are interested less in brick landmarks and Saints’ tombs as the exoticism of the East: Everyday life, national traditions, costumes, the narrow streets of the old part of the city, bazaars, and tandoors,” Bukharsky said.

“Tourists want to capture all this on camera, and up till now they’ve done so without any problem. Time will tell whether the new law will deter potential tourists.”

Uzbeks are generally open to being photographed, but the ban could shift the culture in places such as markets that are favoured by camera-wielding tourists.

A residential street in Samarkand.

A residential street in Samarkand.

Some fear the law will give the authorities the power to pre-emptively stifle the work of independent journalists and activists. Bukharsky says, “the most important thing is that this new law does not become a source of manipulation or tool for repression against ‘unreliable’ bloggers and media outlets.”

With Uzbekistan riding a surge in interest from tourists, and with ambitious plans to expand the industry, one observer noted that the photo ban is unlikely to be widely enforced.

The commentator posted that “the harshness of our laws are compensated by the optional enforcement of them.”

About the author: Amos Chapple is the senior photo correspondent for RFE/RL and is based in Prague. You can find more of his work on his website and Instagram. This article was also published on RFE/RL.