Poor work conditions fuelling mental health crisis, costing trillions worldwide, shows WHO data

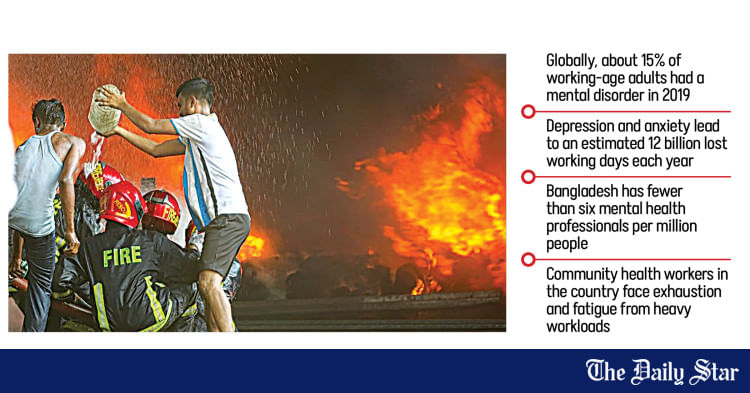

By the time Alam Hossain, station manager of Uttara Fire Service & Civil Defence, reached Milestone School and College on July 21, the campus was in chaos — flames leapt from the Haider Ali Bhaban, smoke choked the sky, and children lay on the ground as parents screamed their names. A fighter jet had just crashed into the building, leaving it in ruins.

“The mental pressure was crushing,” Alam recalled. “All I could think was how to save lives and minimise damage.”

With limited men and equipment, he called for backup. His team spent hours battling fires, pulling survivors from rubble, and rushing the injured and dead to hospitals.

“One teammate tried to pull out a body. As he grabbed the hand, it tore away…. We had to stay professional, but later, as ordinary people, the emotions return. Our families suffer too, as they wait in fear until we come home.”

By the time the operation ended around 9:00pm, Alam was feverish and nauseated from exhaustion.

Firefighters are trained to stay calm under pressure and support victims — yet they themselves receive none. They rely on grit and each other to survive repeated exposure to death and disaster.

That invisible weight is not unique to them. It grips others at the frontline of tragedy — including journalists.

Print journalist Naima Rahman (not her real name) still remembers writing the caption for the viral photo of July martyr Golam Nafiz — a protester slumped in a rickshaw, flag tied to his head, legs hanging on one side, head on the other. “My fingers trembled as I typed. That image never left me — it shows up in dreams, at the dinner table, in the silence before sleep.”

She also spoke with parents of slain children, some showing her bloodstained clothes, schoolbooks, and awards as they spoke.

For female journalists, the strain doesn’t end in the field. They face harassment and struggle for recognition in male-dominated newsrooms — then return home to caregiving and unpaid labour. With little workplace support, this double burden steadily chips away at their mental health.

In corporate towers, the pressure takes another shape.

Rafiqul Islam, 36, a relationship manager at a non-bank financial institution, officially works eight hours a day. But his hours often stretch to nearly 12 under relentless monthly targets.

“Every day feels like a race against numbers. If I fall short, scrutiny is immediate. Even when we do well, no one acknowledges our effort. I come back exhausted, snap at my family, and can’t sleep.”

Workplace stress is not just a personal burden; it carries social and economic costs.

According to a 2024 World Health Organization report, poor working environments — discrimination, inequality, excessive workloads, low job control, and job insecurity — pose serious mental health risks.

Globally, depression and anxiety cause around 12 billion lost working days each year, costing USD 1 trillion in productivity. In Bangladesh, research on workplace mental health remains scarce.

The crisis is worsened by a shortage of professionals. Bangladesh has only 260 psychiatrists and 565 psychologists — fewer than six per million people, mostly in cities, according to a recent Icddr,b report.

With over two decades of experience, Monira Rahman, founder of the Innovation for Wellbeing Foundation and country lead for Mental Health First Aid Bangladesh, said wellbeing is vital across sectors.

“In these fields, employees often face direct or secondary trauma. Without support, how can they keep performing?

“Wellbeing ensures personal resilience and institutional strength. Leaders must understand that investing in wellbeing is not a luxury; it directly improves performance.”

Research shows that “wellbeing inspires well-doing”: every USD 1 invested in treating depression and anxiety yields a USD 4 return, Monira noted.

Experts cite workplace culture as a key stressor: long hours, rigid supervision, constant availability, bullying, job insecurity, and lack of recognition. Women face a double burden, while social media overuse, sleeplessness, and financial pressure add to the strain.

Clinical psychologist Ismat Jahan, head of the National Trauma Counselling Centre, said stress also stems from office politics, poor communication, and difficulty balancing work and personal life.

“Stress manifests physically as headaches, high blood pressure, or fluctuating blood sugar, while damaging relationships through irritability, anger, burnout, and marital strain.”

The toll is visible among community health workers too. A BRAC study published in August 2025 found that overwhelming workloads, irregular pay, poor supervision, and pressure to meet targets caused tension, sleeplessness, and fear of infection.

Despite these symptoms, workers coped silently through prayer, hobbies, or talking to peers.

Stigma remains a barrier, with many fearing that seeking counselling will make others think they are “crazy.” “Even in organisations offering free counselling, employees often hesitate to use it,” Monira said.

SMALL STEPS, BIG IMPACT

Ismat Jahan advocates linking organisations with counselling services and offering stress management workshops.

“Simple steps — occasional sessions, counselling access, or partnerships with mental health providers — can reduce anger, improve relationships, and boost productivity. Mentally well employees make better workplaces.”

One example is the Wellbeing Ecosystem Bangladesh Network, led by IWF. It brings together leaders from education, health, ecology, and the arts to create stronger workplace support systems.

As the sole license holder of Mental Health First Aid (MFHA) Bangladesh, the network runs awareness campaigns, trains leaders, and helps managers spot early signs of stress, anxiety, or depression.

In several banks, corporations, and development organisations, trained managers identified long-standing depression cases, and staff who sought counselling reported improved wellbeing and performance.

Monira said solutions need not be costly. “Empathetic listening and checking in on employees build trust and gradually shift workplace culture. Even small acts can ripple across an office, creating a healthier, stronger, and more compassionate workforce.”