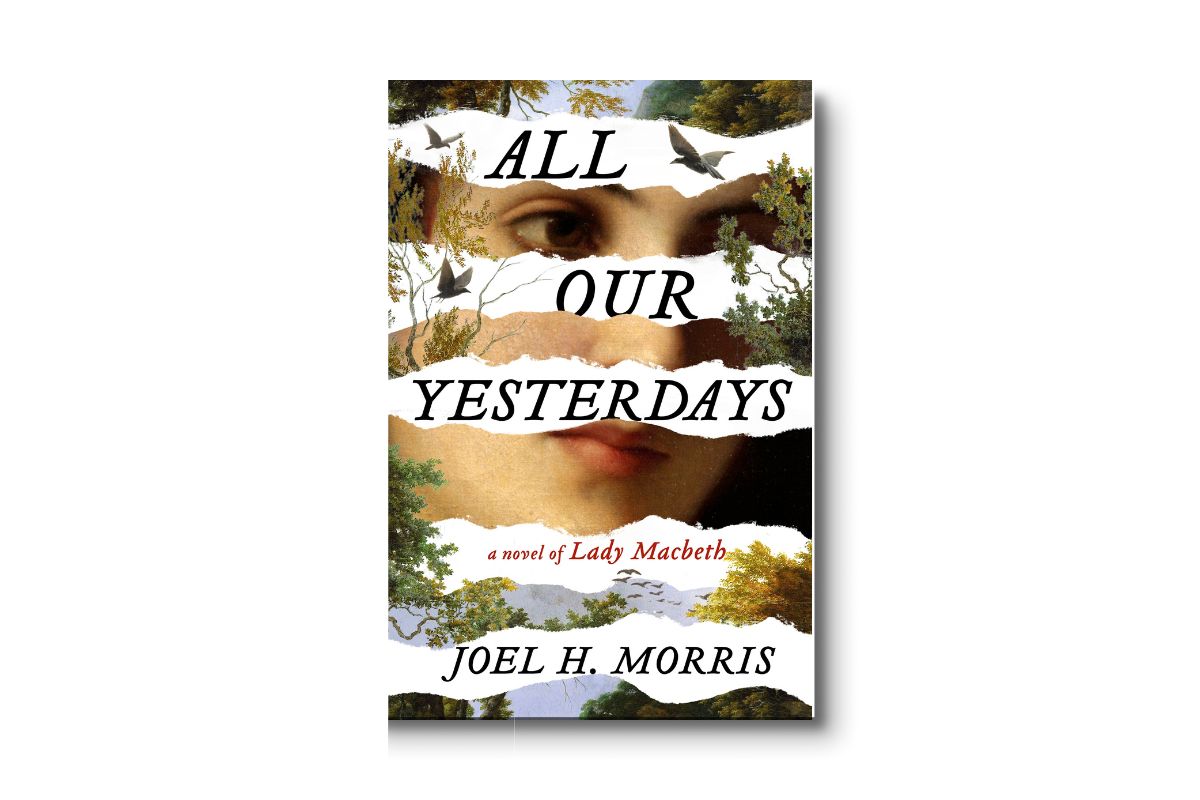

This book won the 2025 Colorado Book Award for Historical Fiction.

I was a girl. My hair was plaited, my nose slightly upturned. I did not like the sight of my wolf’s tooth in the glass. I fought to keep it lipped.

My mother died when I was born. I was her murderess.

My father never spoke this fact. It shaped the silence between us. Not that he didn’t love her. He did, I am sure, in his own way. But my father was not a man who showed love. What must such love have looked like?

I grew up under his foot. Under his brand of love— needy, demeaning love that did not love back. He loved others. Women slid through the house like eels. A few of them took interest in me. I was the granddaughter of a former king, after all. An old king of whom people spoke with reverence, when they remembered him. But they did not remember him much.

UNDERWRITTEN BY

Each week, The Colorado Sun and Colorado Humanities & Center For The Book feature an excerpt from a Colorado book and an interview with the author. Explore the SunLit archives at coloradosun.com/sunlit.

I was my father’s fourth child; two sisters and a brother had come before. They were no more than babes when they died. My second sister lasted the longest—she was two. I would often visit their graves in the castle crypt. I would steal down there and find my sisters, my brother, where they lay under stone. Asleep. Please, wake up, I would beg them. But they never did. They were dead before I was born, but then I had come along and killed their mother. That was the reason they refused to play. How they must have hated me— the fourth, the last, the only. The mother killer.

What might my life have been had she lived?

Sometimes my cousin Macduff would come to my father’s castle from Fife to visit. Those were happy days with him. He was kind, even if my aunt and uncle did not approve of me. I was an odd girl, wayward, wandering. Hardly becoming of my station.

Mostly I was alone. I roamed the woods, headed to a little dell where a ropey brook cut through the mossy banks. I conjured my dead brother and sisters there, setting their ghostly faces before me in the glade. They must look like me, I thought. Only lovelier. Fair faces, flushed cheeks. None of them had the wolf’s tooth that I had, but instead they smiled with even red lips and fine white teeth. My older sisters were brilliant but modest. My brother was cheeky and charming. We played hide-and-seek among the rocks and trees. The rooks flitted in the canopy above; the crickets sang. Owls peered out from their hidden hollows. I hid. I waited. I listened to the wind’s susurrations, felt the chill rise like quills on my skin. And what if I was never found? Would my father come with his many men, hunt me down, and find me behind a half-rotted stump?

When I tired of waiting, I wound the forest path home, plucking flowers, leaving them on my siblings’ stones in the manse’s crypt. I remember believing that if I died, I could join my sisters and brother in their happy dancing and, clasping hands, we might run off from our graves into the moonless night.

“All Our Yesterdays”

>> READ AN INTERVIEW WITH THE AUTHOR

Where to find it:

SunLit present new excerpts from some of the best Colorado authors that not only spin engaging narratives but also illuminate who we are as a community. Read more.

When her mind was not fouled by fog, my grandam would sometimes walk the woods with me. On our walks she would point out the flowers, the herbs. She mentioned the many uses of rhubarb, which she collected for her swelling joints. She told me stories of sprites who lived under flower petals, who must not be disturbed. She gathered flowers of witch’s gowan, also called globe. She burned juniper and cleansed the castle of harmful spirits. At home, by the light of her lonely fire, she showed me needlework; she showed me writing. She listened as I played the harp. For hours we sat together, through the cold and the warm, an endless series of days.

She was my father’s mother, and she had once been queen. I tried to imagine her girlhood, to look past the long ropes of her snow- white hair. She barely spoke of those days. Like my grandfather, she was a woman history had forgotten. Unlike my father, she expressed no bitterness over it.

Then she died.

Who says the world does not change overnight?

I never knew if my father loved her. “Old witch,” he sometimes called her when she disapproved of his carousing. Her passing did nothing to change him, did nothing for his relationship to me. I was the last living member of his family. “We’ll see you married soon enough,” he told me.

On my fifteenth birthday he saw it done. My father regarded my face, gently lifted my chin.

“You are a woman,” he said. “It is time to stop being impertinent.”

Him I could look in the eyes. The man waiting in the hall below was another story.

The man was no friend of my father’s, merely an ally. The Mormaer of Moray. There was not a soul who didn’t know him. He was almost as powerful as a king. Or perhaps just as powerful—King Malcolm, ruler of all, left him alone and turned a blind eye to his bloody campaigns as long as they didn’t threaten the kingdom.

My father had arranged it without my knowing. In three days we would be wed.

I kept my eyes on his feet, my head bowed in modesty as the mormaer and my father spoke. We were surrounded by my father’s attendants, an audience to our introduction. The mormaer surveyed me, his eyes moving from top to toe. He stepped to my side, then behind, assessing. I was a statue awaiting his appraisal.

“Look at me,” he said once my father had fallen silent.

I did. He was not an ugly man. His brow was heavy—it cast a shadow over his eyes—and he wore a great beard, which I suspected concealed a scar of some sort. But not ugly. At least there was that.

He was old. Not so old as my father, but still. He must have seen me as a child. A wife and a child.

“You do needlepoint, I suppose?” he asked.

🎧 Listen here!

Go deeper into this story in this episode of The Daily Sun-Up podcast.

Subscribe: Apple | Spotify | RSS

“Yes, my lord.”

“And you play music, and mincing games, and all of that?”

“Aye, my lord.”

“That will do. You will bear me a half-dozen sons, each the image of his father, each stronger than the last.”

The wedding was a haze, as though a gauze had been placed over my eyes—I recall so little of it. I remember the perfume of flowers. I remember saying words. We were a noble house, a house of ceremony. Words spoken were binding words. It didn’t matter that they were written in air; the words encased us, bound us like the cloth lain over our united hands. In this way there was no doubt: I was his.

Yet, apart from the sons he imagined he would sire, he did not seem to care for having a wife. He preferred the company of men. He surrounded himself with friends and allies. Boisterous men who cowered before him, who sought his company, his approval. They ate together, drank together. Together they howled and neighed. Only once the table filled and the men had sated themselves did my husband then call for me to come to him. Each night I was his walking statue, presented so that men’s eyes might feast on me.

Whenever I entered, the hall fell into silence. The last of the conversation died, and the laughter stilled. They watched as the firelight sent red flourishes dancing across my form.

“Play us a harpsong,” the mormaer called.

I played my harp for them.

“Sing,” he brayed.

I gave words to the songs. Words that conjured my brief life before this one. In those words my childhood rose up before me and I was there, in that former time. I wished to be swept away, carried forever on those songs to simpler days, a lonely girl in her father’s castle. But reality hung before my eyes. Between it and the memories I was torn in two. No wonder our bodies are split, a seam running down our spines. We are stitched together in our mothers’ wombs, divided between the fleeing past and the life to come.

I sang. The men salivated, drooling down their beards, little lapdogs hungering after the wolf’s dinner bone. Then, remembering where they were, they came to attention. The wolf only let them see the feast, not partake of it. Later, they might go home to their wives, to their mistresses, set upon them, devour them. Might those men be thinking of me? I was the sauce to their supper, bride of the Mormaer of Moray.

The great wolf himself made his way to our chamber, full of drink and meat. I could smell his musk, smell the stag fat in his beard, see the gristle between his teeth. He turned me around, pawing at his prey. His broad shoulders heaved. He grunted like an animal, and when he satisfied himself, he rolled over in the furs of our bed and fell into his carnal sleep.

He was seldom home. He preferred the heath to the hall. He preferred the mountains and the dales. He hunted. He roamed. He wrapped his hands around the necks of rebels. He lobbed off heads and set skulls on pikes.

I was left alone, a girl-child expected to oversee the house. When he returned from his roaming he came to our bed with blood on his lips. Whether it was from his quarry or his enemies, I didn’t ask.

My father never wrote. Nor did he visit, happy to be rid of his final, unruly child at last. The next time I saw him, he was dead. Word had traveled that he was growing ill and, should I wish to see him before he departed, I must go to him at once. The mormaer granted me horses and servants, instructed never to leave my side. Perhaps he thought I would run? But where? The entire country was my prison. I had nothing left but him.

By the time I arrived, my father was gone. I gazed into the casket and touched that face. A lifeless picture, pallid, crowned with posies. The dead look nothing like the sleeping.

At his funeral I grew sick. A wave of nausea overwhelmed me, and I swooned. The gentlewomen thought I fainted from grief. But I was not sad, not sorry. I was pregnant.

My great fear had come true. The moment my father had married me off, I had known it was a possibility, but I’d held out hope that there would never be a baby. And so it was, just as the black-robed woman had said.

But a boy?

Alone at night I would pull up my nightgown and hold a candle close to my stomach. I would watch it swimming within me. I watched, unbelieving, then believing and amazed. Once I saw the outline of a hand (a foot?) pressing out from my skin. Then, like a fish, it sank into the depths again. The growing child would shift and roll, and I would feel it so deeply, so perfectly, that I began to believe that the baby had always been there, that it always would be.

I waited to tell the mormaer until there was no hiding it, until I was certain it was true. He was more than pleased.

“You bear a sacred obligation,” he told me, his rough hands tracing the surface of my swelling globe. “And it will be a boy.”

For a man like him, it was the only possibility. He knew the strength of his seed.

Joel H. Morris is the author of the USA Today bestseller, ”All Our Yesterdays,” his debut novel. He teaches English at Cherry Creek High School. Prior to that, he taught college and worked as an officer aboard small maritime expedition ships. His essays, translations, and stories have appeared in Literary Hub, CrimeReads, Electric Literature, and elsewhere. He lives near Denver, Colorado.