They also expressed misgivings after MGB told the Globe that some of the 12 doctors handling the telehealth appointments are located outside Massachusetts. Physicians out of state, the critics said, may not know the local health ecosystem, including specialists to whom they might want to refer patients.

Regardless, the Care Connect system is the latest example of how AI is reshaping health care. Already, artificial intelligence is helping doctors generate clinical notes and interpret X-rays and CT scans, and aiding pharmaceutical companies in their hunt for potential drugs.

But using AI in primary care inserts the technology into the relationship between doctors and patients. While no one expects AI to replace doctors, it could become an entry point into the health care system for patients, a key tool in determining how physicians treat them, and a new model for delivering care.

In an April study published in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine, researchers found that an AI system created by the same tech company that made MGB’s matched doctors’ diagnoses and treatments two out of three times. When there was a disagreement, the chatbot proved right twice as often as the physician. And the AI model is only expected to improve as it interacts with more patients and reviews more medical records.

Care Connect has already received a good review from one patient.

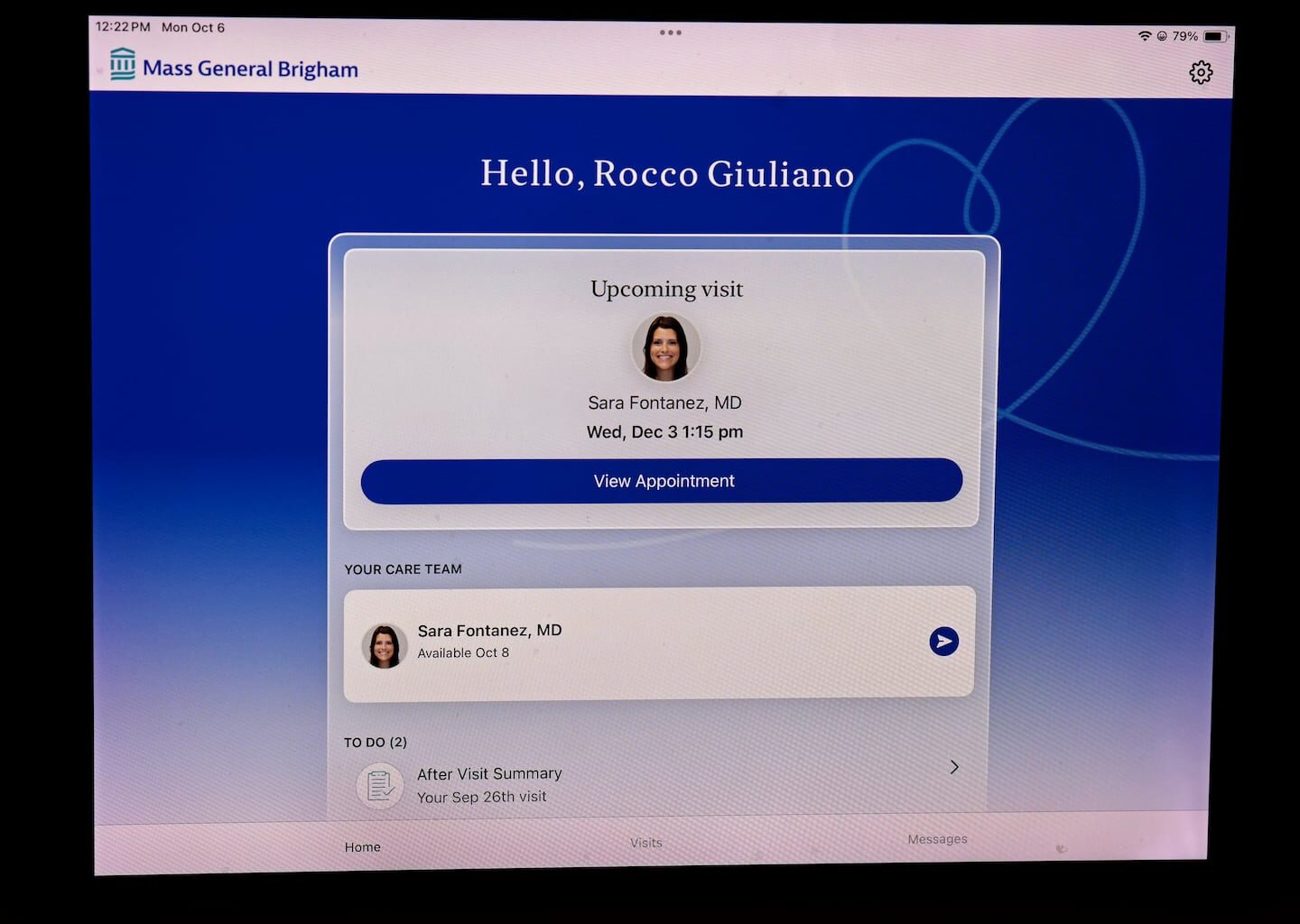

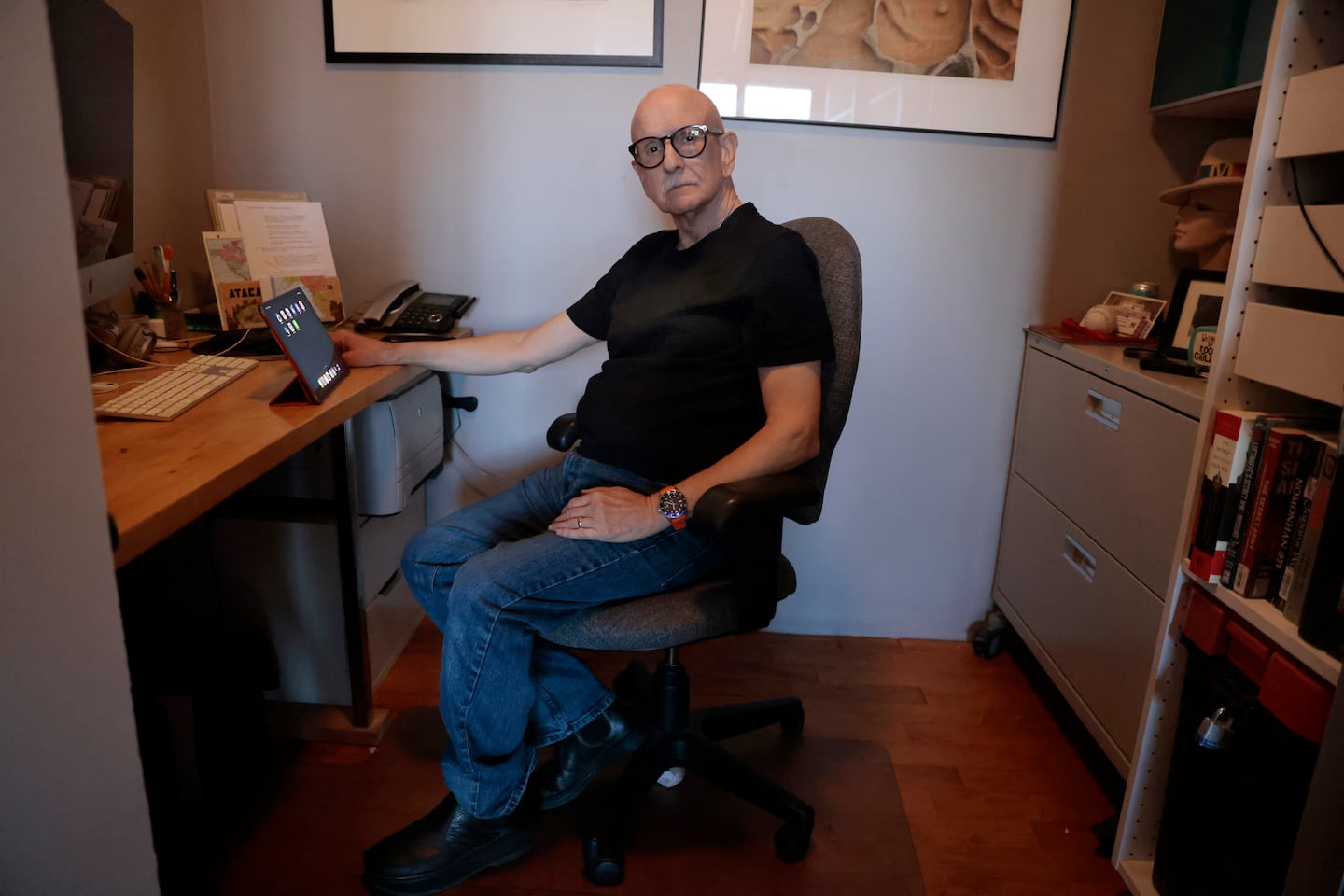

Rocco Giuliano, a 77-year-old Boston documentary filmmaker, has struggled to get medical services as basic as renewing prescriptions since his doctor left MGB for a rival health system about a year ago. But recently, when he began to run low on three blood pressure medicines, he downloaded the app, answered questions posed by the chatbot, and got a telehealth appointment the next day with a doctor who promptly wrote the new prescriptions.

“This is a lifesaver,” said Giuliano, whom MGB offered for a Globe interview. “Given the choice, I always prefer to see people in person. But this has basically solved my problem.”

Rocco Giuliano, 77, recently downloaded Mass General Brigham’s new app, Care Connect, answered questions posed by the chatbot, and got a telehealth appointment the next day with a doctor who promptly wrote new prescriptions for his blood pressure medicines.Pat Greenhouse/Globe Staff

Rocco Giuliano, 77, recently downloaded Mass General Brigham’s new app, Care Connect, answered questions posed by the chatbot, and got a telehealth appointment the next day with a doctor who promptly wrote new prescriptions for his blood pressure medicines.Pat Greenhouse/Globe Staff

David E. Williams, president of the Boston consulting firm Health Business Group, said Care Connect could prevent patients with routine medical problems from visiting expensive emergency rooms and urgent care facilities — and get those patients treated faster.

But several primary care doctors at MGB say the AI platform is just a Band-Aid for deeper problems. They say MGB doesn’t do enough to retain and recruit primary care doctors and could remedy that by paying higher salaries, providing more support staff, and giving doctors greater say in decisions that affect their practices.

Dr. Michael Barnett, a primary care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an organizer of a new union of such doctors at MGB, said that rather than roll out the AI platform, the health system could simply add eight to 10 primary care providers to a full staff of such practitioners.

“It’s not rocket science,” said Barnett, a professor of health services at the Brown University School of Public Health. “The [AI] service is fine. But it’s like your local neighborhood restaurant getting replaced by a vending machine. It’s not a full replacement.”

Dr. Helen Ireland, a senior medical director at MGB who helped launch Care Connect, said the health system has worked hard to recruit primary care physicians. In the past two years, MGB said, it has hired more than 110 such doctors to help fill vacancies. (MGB currently employs 657 primary care physicians.) But it can take a year to get a doctor licensed in Massachusetts, credentialed by the system, relocated, and up to speed at a new practice.

In the meantime, Ireland said, the AI-powered app will serve as a bridge for patients who may not be able to see a doctor in person for months or need help managing chronic conditions. Some patients, Ireland added, may prefer the chatbot and virtual visits to going to a doctor’s office.

“This does not replace our other efforts,” said Ireland, a primary care doctor in Beverly.

Care Connect is a partnership between MGB and K Health, a New York AI firm. K Health has set up similar digital platforms for several large health systems facing shortages of primary care doctors, including Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles and Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Dr. Caroline Goldzweig, chief medical officer at Cedars-Sinai Medical Network and coauthor of the study in the Annals of Internal Medicine, said her health system introduced its version of the app two years ago. It is available to any California resident; at least three-quarters of the 50,000 patients who have used it have received treatment at Cedars-Sinai and lack a primary care physician.

Goldzweig said the AI system harnesses information collected from millions of medical cases and makes reliable treatment recommendations to the doctors who see patients afterward virtually. K Health calls those physicians “virtualists.”

Goldzweig emphasized that the chatbot doesn’t treat the patients — doctors do. But the bot reviews patients’ electronic medical records, generates potential diagnoses, and saves the physicians time.

“The AI is not a doctor,” she said. “The AI is trying to augment the doctor and make the doctor more efficient.”

The corporate offices of Mass General Brigham in Somerville in 2022.Lane Turner/Globe Staff

The corporate offices of Mass General Brigham in Somerville in 2022.Lane Turner/Globe Staff

Not all cases are suitable for online treatment. In some cases, said Goldzweig, the chatbot may set up a telehealth appointment with a doctor who tells a patient, “‘You need to go to urgent care’ or ‘You need to go the emergency room. I can’t handle this.’”

K Health, MGB, and Cedars-Sinai all declined to say how much the AI platform costs health systems.

Although the shortage of primary care physicians is a nationwide problem, it’s particularly severe in Massachusetts. The state Health Policy Commission said in a report in January that primary care in Massachusetts faces a “dire diagnosis.”

More patients are reporting difficulty finding doctors. Physicians are struggling with overwhelming workloads. The corps of primary care providers is aging, and the medical education system isn’t producing enough doctors to replace them.

Dr. Zoe Tseng, a primary care doctor at Brigham for the past 11 years, said she and her colleagues had little to no input in the decision to launch the AI platform, which she described as emblematic of how MGB regards primary care doctors.

“We’re talking about the primary care physicians whose patients are being affected by these programs that they’re rolling out,” said Tseng. “We feel just like a cog in the wheel.”

On Sept. 26, the new union, the Doctors Council of the Service Employees International Union, wrote to high-ranking MGB executives asking, among other things, whether the health system intends to deploy Care Connect instead of hiring new primary care providers.

An MGB spokesperson told the Globe that Care Connect “is not a replacement for in-person care.”

Dr. Kristen Gunning, a primary care physician at Mass. General for 17 years, noted that 10 primary care doctors from a single Brigham practice in Chestnut Hill last year defected to join a new practice in Wellesley affiliated with rival Beth Israel Lahey Health. Together, those doctors cared for roughly 13,000 to 15,000 patients a year — roughly the number of patients currently without primary care providers.

If MGB “treated us better,” said Gunning, “they wouldn’t be losing so many doctors.”

Jonathan Saltzman can be reached at jonathan.saltzman@globe.com.