After giving birth to twins, Ivana Poku battled postpartum depression and intrusive thoughts—now she helps other mothers understand that they are not alone.

When her twins were just a few months old, maternal mental health advocate Poku, who lives in Scotland, was sitting at home alone with one baby on her lap and the other strapped into a bouncer. The afternoon was quiet until, suddenly, something inside her shifted.

“It was like something possessed my brain and my body,” she told Newsweek. “I felt this strong urge to hurt him.”

A small part of her—what she now calls her healthy part—recognized the danger. She quickly strapped the baby into the chair, ran into her bedroom and locked the door.

Then she sat there, terrified of herself. In that moment, she realized something was terribly wrong.

“It’s not like you’re sitting there thinking, ‘Let’s hurt my baby,’” Poku said. “It’s not you. It’s an illness and this is the symptom of the illness.”

Poku, who was 32 at the time, said that her mental health had been unraveling quietly since the birth of her twins. While she was never officially diagnosed with postpartum depression, looking back she believes it is obvious what it was—perhaps even bordering on postpartum psychosis. When the babies arrived, she didn’t feel the rush of love she had been told to expect. Instead, there was numbness and guilt.

“Postnatal mood changes are more common than many people realize,” clinical psychologist and trauma expert Dr. Shahrzad Jalali—author of The Fire That Makes Us—told Newsweek

She continued: “About 70 to 80 percent of new mothers experience what we call the ‘baby blues’ in the first few days after giving birth. This is a short lived emotional period, the symptoms are mostly like tearfulness irritability mood swings but typically resolve about two three weeks in at most six weeks.”

“When these symptoms last longer or begin to interfere with daily functioning, we start to look at what we call postnatal depression, which is a clinical diagnosis. This affects roughly one in seven people worldwide,

“It’s not unusual for mothers experiencing postnatal depression or anxiety to have intrusive or frightening thoughts, like feeling they may harm their baby or wishing their children weren’t there. These thoughts are deeply distressing and unwanted, and usually the mother would not act on it.”

‘Inside I Was Breaking’

“I didn’t feel happy,” Poku said. “I thought that made me a horrible mother.”

Poku recalled how she missed her old life, felt disconnected from her new one and began to despise herself for it. “The silence was the killer,” she said. “I was pretending to be okay, but inside I was breaking.”

Her thoughts grew darker. Sometimes she would watch her babies sleeping and imagine if they never woke up. “I’d think, ‘If they died, that would be amazing,’” she said.

The family had just moved to a new town. There were no friends nearby, no relatives to help and her husband worked long hours. “Most of the time it was just me,” Poku said. “No friends, no family, no support. That’s not okay.”

At the time, she did not realize she was ill. “You don’t know you have depression,” she said. “You just feel like you’re failing—that everyone else is enjoying their babies and you’re not.”

The shame kept her silent. Though she was given leaflets and phone numbers for support lines, reaching out felt impossible. “They tell you to call someone, but when you’re in that state, it’s the last thing you can do,” she explained.

The turning point came when a friend dropped by unexpectedly and found her in the depths of despair. “There was no way I could hide it,” Poku said. “I told her everything, and she didn’t judge me. That was so liberating.”

Her husband’s support also helped pull her through. He reminded her that she was raising twins alone, without a support network, and that struggling didn’t make her weak—it made her human. “When I gave myself some compassion everything started to change,” she said.

Finding Purpose in Pain

Finding Purpose in Pain

Poku’s change did not end with her recovery, but instead sparked a mission. She began speaking to other mothers and discovered that even the ones who seemed to have it all together were often quietly suffering too. “I realized it wasn’t just me,” she said. “And I knew it was my duty to make a difference for future moms.”

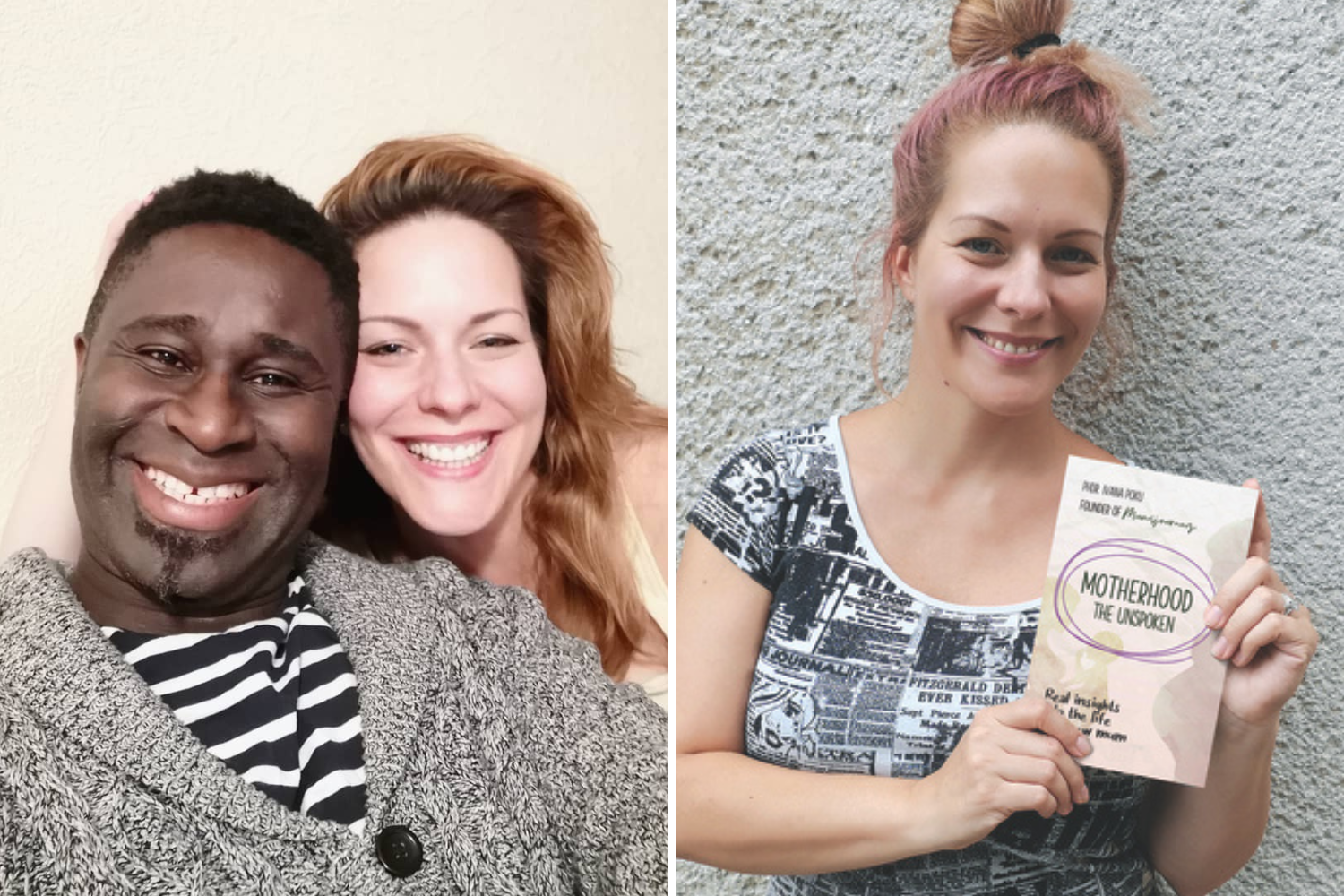

She launched Mum’s Journey, a blog where she writes honestly about the realities of motherhood, postpartum mental health and recovery—and later published a book, “Motherhood: The Unspoken.” The book brings together stories from mothers around the world, offering what she described as “a comfort hug in book form.”

Poku also runs a course on preparing for postpartum emotional wellbeing, designed to help expecting mothers understand the challenges of new motherhood—not to scare them, she stresses, but to make sure no one feels as unprepared and isolated as she once did.

“If I had known those feelings were normal,” she said. “I wouldn’t have struggled in silence. Proper education is essential.”

This is something that Jalali echoes. She said: “The most important thing is for a woman to know they’re not alone and that help is available postnatal depression is a very treatable condition. If a mother notices persistent sadness, loss of pressure, feelings of guilt or intrusive thoughts, she should reach out to a healthcare provider.

“Support from family and friends is extremely important. It’s important for her to not be alone with the baby. And then compassion, no judgment. If you know someone who’s given birth, maybe check up on them. Maybe offer your support because it is a very tough time for a woman.”

Today, Ivana Poku is a mother of three and maternal mental health advocate, mentor and writer, working to dismantle the stigma around postpartum mental illness. She is not a clinician, but her lived experience has made her a trusted voice in the maternal wellness community and a lifeline for women who see themselves in her story.

“Many mothers have told me I helped them more than a psychologist,” she said. “Maybe because I’ve been there.”

Do you have a tip on a health story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about postpartum depression? Let us know via health@newsweek.com.