Every meal of wild game has a story worth telling.

Of course, there’s the story of the hunt, a recounting of the moments that lead to a success for the hunter, but there is much more to it than that. It’s also a story of the ecology of a place, one not consumed by human development.

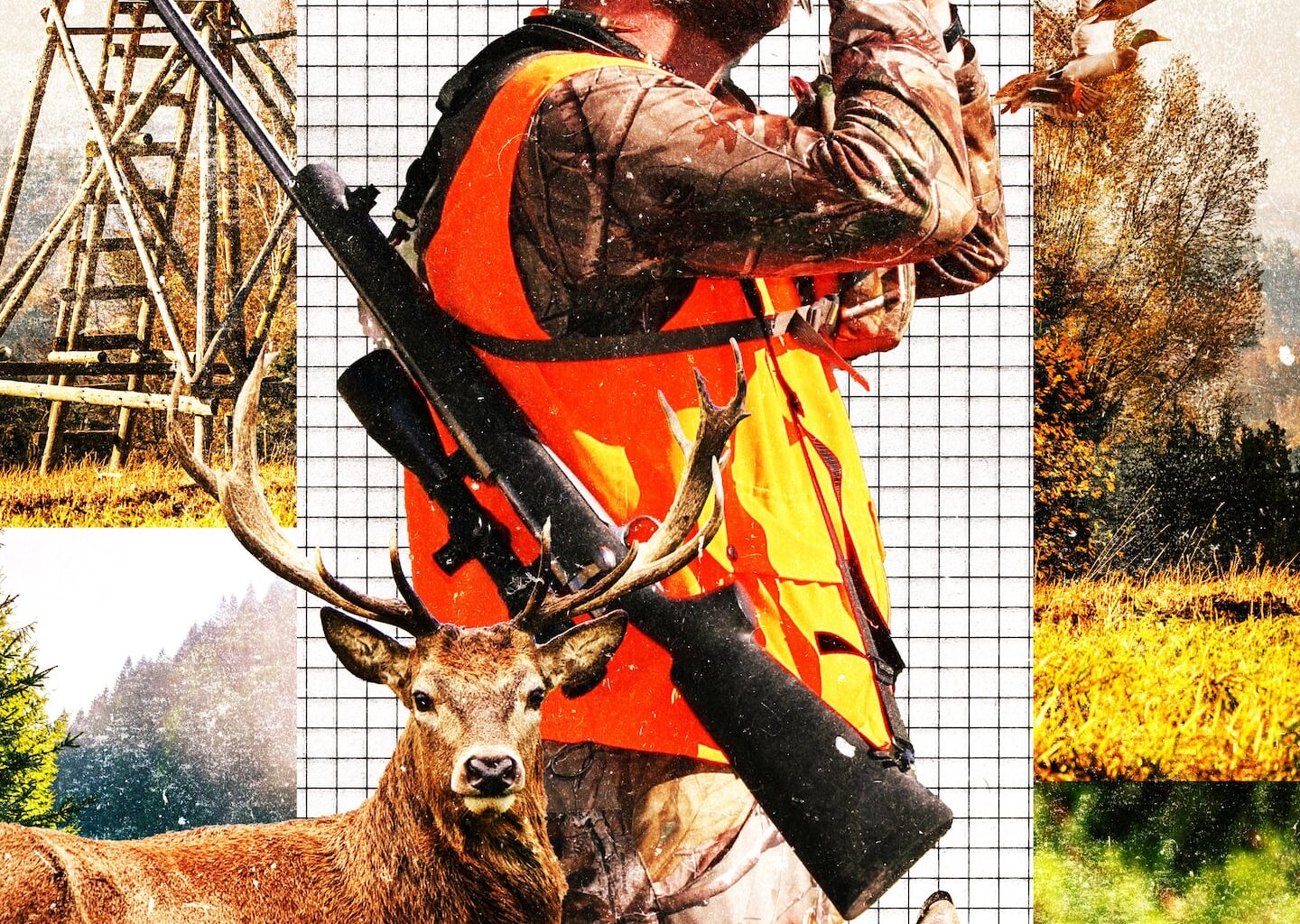

I’m closing in on five decades as an environmentalist, but I don’t think I really understood that story until I started hunting about 15 years ago. I’ve always spent every second I could outdoors. Whether I was hiking, riding a mountain bike, surfing, or paddling a river, I was moving through nature, but not part of it. Hunting changed that.

Typically, people are introduced to hunting by their families or friends, but for me, it started academically. Before taking a leave from a prep school where I taught, I told my Advanced Placement environmental science class that upon my return, I would begin a unit on how the way we produce food affects the environment. As I was leaving, one student asked if I could incorporate hunting and wild food into the unit. Since I wasn’t very familiar with the topic, I promised I’d research it.

I immediately ordered a few books on those subjects. Halfway through the first one, I found myself asking why I’d never thought about hunting before. I grew up on a small farm. My father maintained a large garden, and we raised sheep, chickens, and turkeys for household consumption — so as an adult, I consider carefully where my food comes from. But raising livestock where I live in Newbury isn’t possible, and it had never occurred to me that hunting could be a way to locally and sustainably source a significant portion of my protein. That realization only clicked in after that student’s question. That moment marked the beginning of my hunting journey, which later deepened my connection to the outdoor places I love.

Whether or not a person obtains food through hunting, we are all part of, and benefit from, the same ecological process. In the wilds of the Northeast, the story of food begins with solar energy being converted into chemical energy by the northern hardwoods, oaks, and hickory trees, along with a wide variety of shrubs and herbaceous plants that make up the forest understory. These plants create the foundation for a complex web of feeding relationships, where that chemical energy is transferred from one organism to another, sustaining life. The hunter is part of this system, and just like a deer, squirrel, or rabbit, I am a recipient of a portion of that energy, first captured by the plants of the forest.

When we consume food from modern food systems, we’re at the receiving end of a form of finite ancient sunlight locked away as fossil fuels, which is used to power farm machinery and processing and transportation of food. For the hunter, however, the wild game we consume is not only local but renewably sustained by yesterday’s and today’s sunlight. So, as a hunter, I care about the animals I pursue, as well as the trees, soil, water, microorganisms recycling nutrients, insects pollinating plants — all of which feed the deer and turkeys I hunt, which, in turn, feed me.

When I’m in the woods hunting, deer and the “sign” they leave behind in the forest (markings like rubs on trees, scraped patches of dirt, and bent limbs known as “licking” branches) occupy much of my attention, but I also see the subtle changes in the places I spend hours, still, in one place, season after season.

Perhaps the starkest difference I’ve observed is how different natural landscapes are when there is not a consistent human presence. A trip to my local land trust property or state park that’s fragmented by trails utilized by trail runners, dog walkers, mountain bikers, confirms this reality. Is there wildlife? Sure, but not like in trailless areas, where wildlife only deals with the occasional human intrusion. In these undisturbed places, wildlife thrives without constant human disturbance. Although this was something I knew to be true in theory, it became something entirely different when I began witnessing it in person.

Through hunting, I feel I have a greater stake than ever in ensuring we have clean air and water, healthy soil, and wild places. That’s because in a very real sense, nature now sustains me more completely than it once did. I’ll admit that despite having spent countless hours outdoors, whether that be conducting scientific fieldwork at a remote outpost or cruising down a trail on my bike with flowering lupines up to the handlebars, at times I have lost sight of my intrinsic connection to nature, a connection I celebrate with every meal that I can now trace back to the places I love.