Beneath the surface of the North Atlantic, between Greenland and Iceland, lies a colossal natural phenomenon invisible to the human eye. While most people would name Angel Falls or Niagara when asked about the world’s greatest waterfalls, few know that the true giant flows silently beneath the Denmark Strait. Measuring more than three times the height of Angel Falls, this underwater waterfall challenges everything we think we know about Earth’s extreme landscapes.

Now, a team of researchers is setting out to study this hidden force of nature—not just for its scale, but for its role in regulating oceanic and planetary climate systems.

A Hidden Giant: Discovering the Denmark Strait Cataract

At first glance, the idea of a waterfall existing underwater may seem paradoxical. But the Denmark Strait cataract, flowing from the Greenland Sea into the Irminger Sea, proves otherwise. Here, cold, dense water from the Arctic descends beneath warmer waters from the south, plunging over a dramatic drop in the seafloor more than 3,500 meters (11,500 feet) deep. Stretching 160 kilometers (100 miles) wide, and moving 175 million cubic feet of water per second, this underwater cataract dwarfs every waterfall on land.

The process is not driven by gravity alone, but by the thermohaline circulation—a critical component of global ocean currents. As explained by the National Ocean Service, the density difference between cold and warm water causes this massive flow to sink and cascade. It’s a hidden current that not only sculpts the seafloor but also sustains the conveyor belt of global ocean circulation.

The Science Behind a Submerged Spectacle

While gravity creates dramatic falls on land, underwater waterfalls follow a different dynamic. It’s temperature and salinity—not elevation—that drive this deep-sea descent. When frigid water masses from the Nordic Seas encounter warmer waters in the Irminger Basin, they sink. This natural density contrast pulls vast volumes of water downward, creating what researchers call a density-driven waterfall.

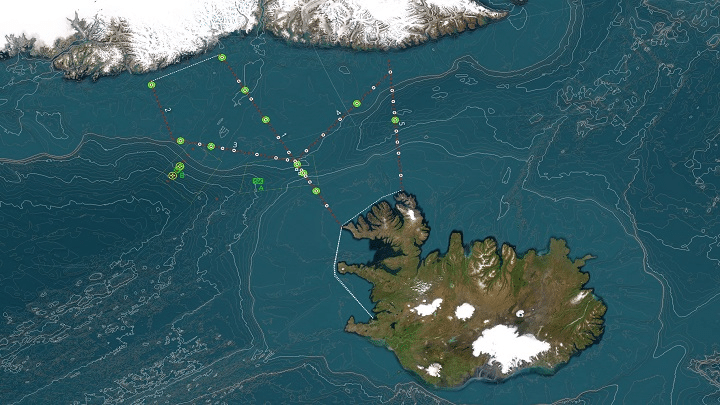

This phenomenon was first identified in 1989, but our understanding of its implications is still evolving. According to the University of Barcelona, scientists are now embarking on a focused expedition to study this process in greater detail. Led by Professor Anna Sanchez-Vidal, the project aims to understand how climate change is affecting this massive underwater system.

“A good example is on the Catalan coast, where the decrease in the number of tramontane days in winter in the Gulf of Lion and north of the Catalan coast is causing a weakening of this oceanographic process, which is decisive in regulating the climate and has a great impact on deep ecosystems,” said Professor Sanchez-Vidal in a statement published by the University of Barcelona.

Climate Change And The Collapse Of A Natural Engine

The Denmark Strait cataract does more than shift water—it shapes the Earth’s climate. This invisible waterfall is one of the engines behind thermohaline circulation, helping drive the deep-ocean currents that redistribute heat, carbon, and nutrients across the globe. But as global temperatures rise, the stability of this deep-sea process is under threat.

Warmer ocean temperatures and increased freshwater influx from melting ice caps reduce the density of northern waters, weakening the descending flow. As less cold water sinks, the conveyor belt slows, leading to major changes in ocean dynamics. This has downstream consequences: disrupted nutrient flows, weakened climate regulation, and altered marine ecosystems.

The stakes are high, and the expedition led by Sanchez-Vidal is set to provide unprecedented data on how the waterfall is responding to a warming world. Her team will monitor changes in temperature, salinity, and current strength to determine whether this natural engine is slowing—and what that means for future climate models.

More Than Just A Geological Oddity

It’s easy to dismiss an underwater waterfall as an exotic curiosity. But what lies beneath the Denmark Strait is a key driver of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which helps stabilize climate systems from North America to West Africa. Its weakening could result in colder winters in Europe, stronger hurricanes in the Atlantic, and rising sea levels along the US east coast.

By highlighting places like the Catalan coast, Professor Sanchez-Vidal links localized weather changes to global processes. Her quote underscores the subtlety and seriousness of these transformations—what may seem like fewer winter winds in one region might signal a breakdown in planetary balance.

These insights, supported by institutions like the National Ocean Service and the University of Barcelona, reinforce the urgency of understanding—and protecting—this hidden giant.