The landscape in Kula is dry and brown in July. HJI / COLLEEN UECHI photo

The landscape in Kula is dry and brown in July. HJI / COLLEEN UECHI photo

After 71 years of living in Pukalani, Anna Mae Shishido knows the drill during a drought. No watering lawns. No washing cars.

The lama, or Hawaiian ebony, that she grows on her property is currently “teetering” on the edge of dying out.

HJI Weekly Newsletter

Get more stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative’s weekly newsletter:

ADDING YOU TO THE LIST…

“It seems that we always have a drought,” Shishido said. “It’s just longer periods now than before.”

Maui County saw lower-than-average rainfall from May to September in what was Hawai‘i’s third-driest season in the last 30 years, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. And, more than 94% of Maui County is under some kind of drought, the U.S. Drought Monitor shows.

As the need for water continues to outpace supply, especially in Upcountry, Maui County is trying to find new sources and solutions that aren’t dependent on rain. They include buying and drilling new wells, upgrading key treatment plants and potentially connecting to the Central Maui system so water can be pumped Upcountry in times of short supply.

Upcountry residents often bear the brunt of dry conditions because 68% of their supply relies on surface water, which depends on rain, explained John Stufflebean, director of the county’s Department of Water Supply.

Earlier this month, the department upgraded Upcountry to a Stage 3 water shortage, which is issued when demand exceeds supply by 31% or more. Recent rainfall downgraded Upcountry to Stage 2, in which demand exceeds supply by 16% to 30%.

By contrast, the Central Maui system, which serves Central and South Maui, relies on groundwater, while the West Maui system combines groundwater and surface water and Hāna’s system also taps into groundwater.

“We don’t want to have isolated water systems,” Stufflebean said at a community meeting on Tuesday. “We would prefer to have all our water systems connected as much as possible.”

Stufflebean told the Hawai‘i Journalism Initiative that the aftermath of the 2023 Upcountry and Lahaina wildfires “basically took all of our attention for a year” as the department worked to restore safe water to homes and businesses. But as recovery progresses, attention can now turn to other projects and needs.

Upcountry’s water supply, he said, “is one of the top issues.”

DIGGING DEEP

When strong winds knocked out electricity during a big brushfire in Kula on Aug. 8, 2023, the lack of backup power for critical pumps hampered firefighting efforts, Stufflebean told The Associated Press in September 2023.

The pumps needed to push water up into the storage tanks and reservoirs to help maintain the pressure. After the fire, the department invested in generators for Kula and other areas to use in a power outage.

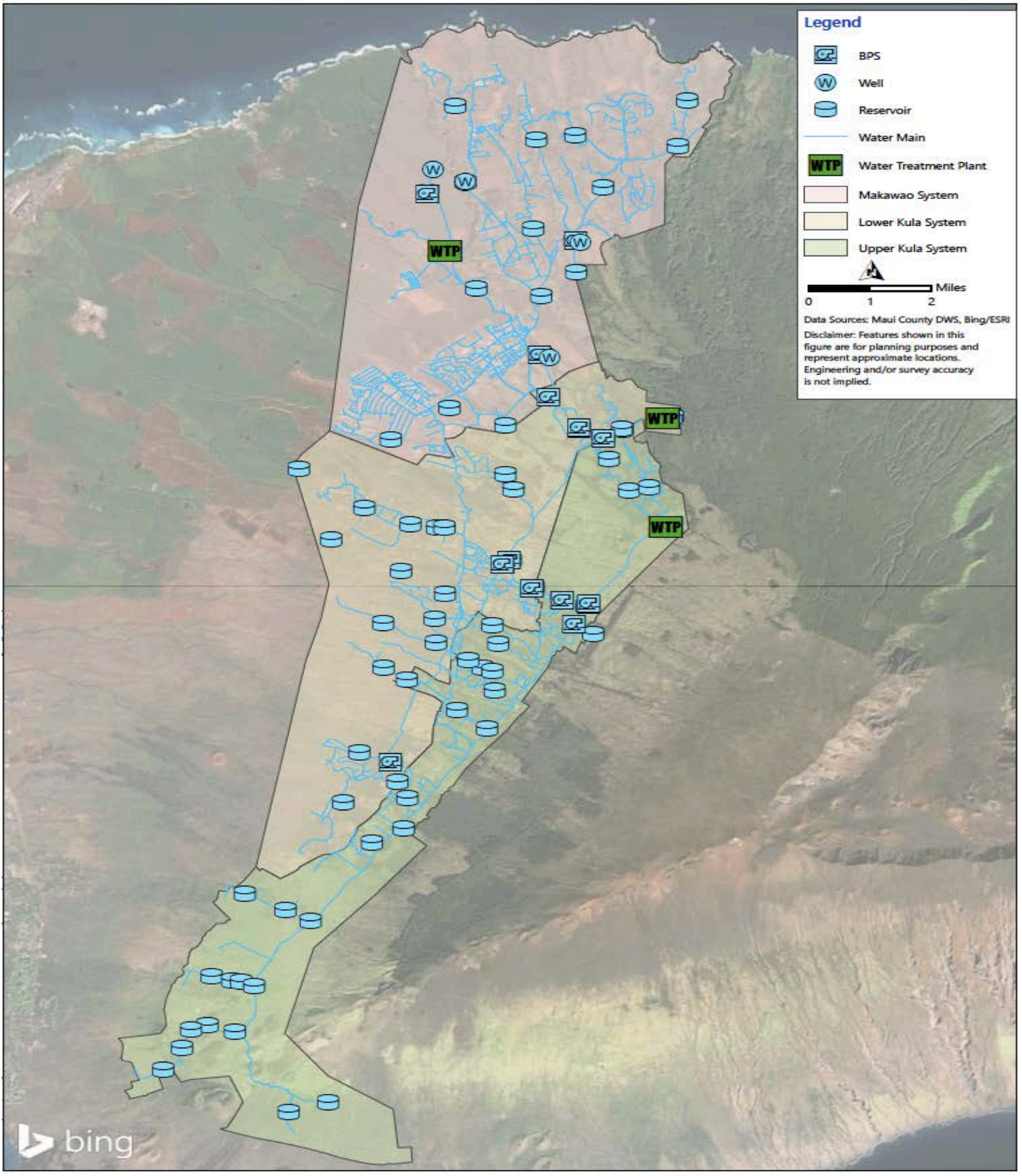

The water system is especially complicated Upcountry, where the county has more than 60 storage facilities across the Makawao, Lower Kula and Upper Kula systems, department maps show. The elevation changes and the topography make it even trickier to maintain, Stufflebean said.

However, the biggest issue is simple. There’s just not enough water.

Upcountry residents listen to the county’s plans to increase water resources for their community on Oct. 28, 2025. HJI / COLLEEN UECHI photo

Upcountry residents listen to the county’s plans to increase water resources for their community on Oct. 28, 2025. HJI / COLLEEN UECHI photo

At peak demand, Upcountry customers use 10.1 million gallons of water per day, exceeding the reliable supply of 9.7 mgd by 4%.

That’s not counting the 1,424 applicants seeking 3,612 water meters Upcountry that would would require an additional 2.16 million gallons per day. The anticipated full buildout of Upcountry under the community plan is expected to need another 4.5 mgd. The state Department of Hawaiian Home Lands has also requested another 9 mgd from the Upcountry system.

And that water demand is expected to keep going up. The Maui Island Water Use and Development Plan projects demand Upcountry to reach 15.7 mgd by 2035. Islandwide, the plan projects the number of residents to grow to 206,884 by 2035, a 32% increase over 2015, and it expects overall potable water consumption to rise to 48.5 mgd, a 47% increase over 2015. Growth in Central Maui is expected to be the primary driver of that increase.

For Upcountry, Stufflebean said the county’s goal at the moment is to meet the peak demand plus the current list of water meter applicants. The department is targeting two key strategies: treatment plant upgrades and additional wells.

At the top of the list is replacing the filter at the Kamole treatment plant, which has been in service since 1998 and is the main treatment plant of the three that serve Upcountry. A new filter will help the plant treat more water and increase capacity from 4 mgd to 5.5 mgd at the plant, Stufflebean said. The project, which is underway and expected to finish in the spring, costs about $5 million.

Stufflebean said the department’s second-most important project is to build two new reservoirs at Kamole. The current fiscal budget includes $1.4 million to design the reservoirs, and the department plans to seek federal funding to help foot the $25 million bill for construction in fiscal year 2028.

The cost is nearly one-third of the county water department’s $90 million annual budget and almost the entirety of its $30 million capital projects budget.

“Things have changed quite a bit in terms of federal funding recently, but we think this is a project that really still has good potential of getting federal funding,” Stufflebean said.

Upcountry’s water system, which covers Makawao, Upper and Lower Kula, is shown. Photo: Maui County Department of Water Supply

Upcountry’s water system, which covers Makawao, Upper and Lower Kula, is shown. Photo: Maui County Department of Water Supply

The reservoirs would have a combined capacity of 140 million gallons, allowing them to capture high flows, enhance reliability and prevent water losses due to turbid or cloudy water that clogs the filters and can’t be sent to the plant.

“By having a reservoir, we can capture that, let it settle out and not lose the ability to treat that water as well,” Stufflebean said.

Another change would involve switching the disinfection process at the Olinda treatment plant from chloramines to free chlorine, which is used by the other two plants. Because they use different treatments, water from the plants can’t be mixed, and that “really limits our ability to move water around,” Stufflebean said.

The department has finished the analysis and is moving toward the design. The cost is still to be determined.

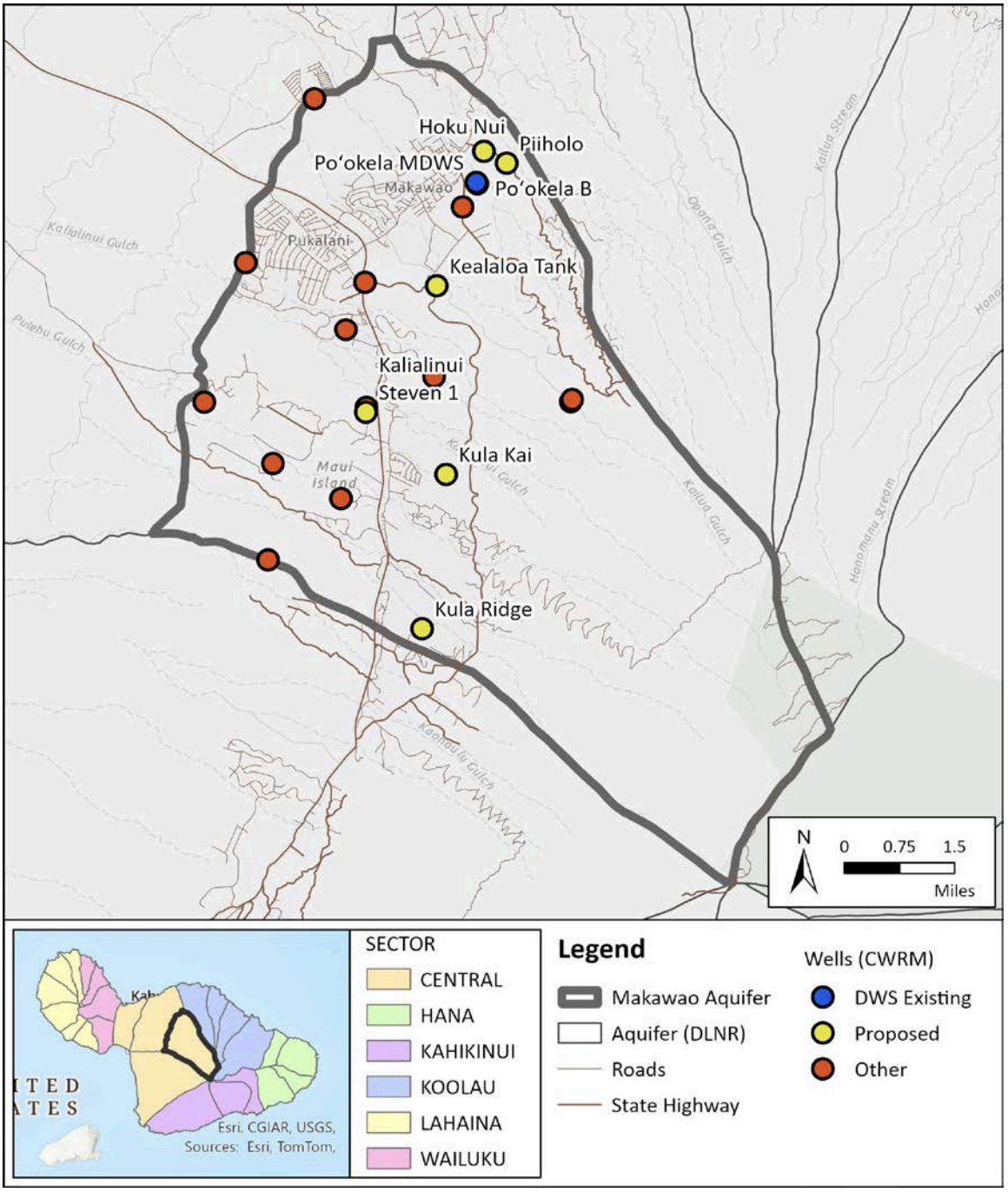

But the solution that the county plans to invest the most in is an increased reliance on wells. The department is considering leasing, purchasing or drilling six wells in the Makawao aquifer, which spans about 229 square miles ranging from the 9,600-foot elevation level near the peak of Haleakalā to 1,100 feet where it transitions to the Pā‘ia aquifer.

As of June, there were 19 wells and tunnels in the Makawao aquifer registered with the state water commission, including six for agriculture, three for municipal county use, three for municipal private use, two for domestic use and one for golf course irrigation. Four are unused. The wells pump an average of 1.9 mgd, including 1.4 mgd from the two county wells.

The aquifer has a sustainable yield of 7 mgd, which is the maximum amount that can be taken without depleting the water source.

The six existing and proposed wells include:

Hoku Nui Well, an existing agricultural well with a capacity of 1.15 mgd. The county wants to buy this well from Hoku Nui Maui LLC, a regenerative farming community. The purchase cost is in negotiations and would require up-front funds for connecting to the county system. It is eligible for general excise tax revenues. Timing to put it in service would depend on the purchase and connection of infrastructure.

Pi‘iholo Well, an unused existing well with a capacity of 0.67 mgd. The county wants to lease this well from Maui Land & Pineapple Co. and pay for connecting infrastructure. However, it plans to wait until Hoku Nui is deemed acceptable because it needs to be coupled with Hoku Nui to be cost effective.

Kalialinui Well, an existing agricultural well with a capacity of 0.96 mgd. The county wants to lease this well from owners Marc and Tara Steven. The cost is in negotiations and the county would pay up-front expenses for connecting to infrastructure.

Kula Kai Well, a proposed well that would have a capacity of 0.96 mgd. The county wants to buy the land from Haleakalā Ranch and drill the well for an estimated total cost of $20 million. Timing would depend on a well-drilling permit and environmental assessment. The department has funding in the current budget for the exploratory phase.

Kealaloa Well, a proposed well that would have a capacity of 0.96 mgd. The well would be developed in partnership with the state, which would use 0.24 mgd for DHHL, with the county getting the rest. The Department of Land and Natural Resources has completed the exploratory phase and is in the design phase. The county would pay the remainder of the costs, estimated at $15 million.

Kula Ridge Well, a proposed well on county-owned land that would have a capacity of 0.96 mgd and the option for multiple wells. It’s currently being studied as a potential project, but the discovery of ‘iwi (ancestral bones) will require time to address. The cost is still to be determined but is expected to be relatively expensive due to deep groundwater.

Purchasing or leasing existing wells will be quicker, likely taking one to three years, Stufflebean said. Construction of new wells is expected to take five to 10 years.

A map shows the locations where the county wants to acquire or drill new wells. Photo: Maui County Department of Water Supply

A map shows the locations where the county wants to acquire or drill new wells. Photo: Maui County Department of Water Supply

Another solution that Stufflebean said is “a little controversial” is connecting the Central Maui system to the Upcountry system. He said he understands that Upcountry residents don’t want to see their water potentially taken elsewhere, but he pointed out that both areas could benefit. If that connection had been in place during the bad drought in October 2023, for example, the department could have pumped water Upcountry, Stufflebean said. He didn’t have an estimated cost for connecting the two systems, saying the department is looking into it.

To cover the costs of the upgrades and new wells, Stufflebean said the county could consider multiple options, including a “pay as you go” strategy where the department spends however much funding it can get that year. There’s also the option to use revenue bonds in which the county gets the money up front and pays for it over the next 20 years.

The county could also use funds from the 0.5% general excise tax surcharge that took effect in 2024 to help pay for infrastructure projects.

Stufflebean said the county is also continuing to pursue federal funding, though that is “still unknown” at a time when President Trump’s administration is slashing funding for dozens of federal programs.

All told, the upgrades and wells could increase capacity by 7.76 mgd. Because the wells’ capacity would exceed the sustainable yield of the aquifer, some would serve as backups. With those limits, total capacity would be 17.7 mgd, just enough for the 16.8 mgd needed to cover peak demand, the water meter list and the full buildout of Upcountry.

Maui County Water Supply Director John Stufflebean talks about Maui’s water resources during a community meeting at the Mayor Hannibal Tavares Community Center in Pukalani on Oct. 28, 2025. HJI / COLLEEN UECHI photo

Maui County Water Supply Director John Stufflebean talks about Maui’s water resources during a community meeting at the Mayor Hannibal Tavares Community Center in Pukalani on Oct. 28, 2025. HJI / COLLEEN UECHI photo

FIRE RISK ON A DRIER LANDSCAPE

Stephanie Okimoto is happy to see the county moving forward with upgrades, but she also says they’re long overdue. She lives in Pukalani and gets a regular reminder of the parched conditions.

“When you drive past the houses, the grass and everything is all dry,” said Okimoto, adding that most of her plants have died.

Sara Tekula, executive director of the Kula Community Watershed Alliance, said the lack of water and the “crispy” landscape impacts fire prevention. The Stage 3 declaration was issued less than a week before a red flag warning, hampering people’s abilities to water their properties to help with fire suppression.

“It’s just sort of this unfortunate set of circumstances happening all at the same time … when we know we are at risk of extreme wildfire,” Tekula said. “So it’s traumatizing. It’s inconvenient for people who are trying to grow for sustenance or for their family or for their community.”

The alliance launched an initiative over the summer to remove invasive wattle trees that push out native plants and increase fire risk. Part of that effort included opening a nursery with plants to help restore Kula’s burn scars. Because of the water shortage, they’ve cut back on watering and are “doing it very lightly by hand” as well as relying on catchment.

Sara Tekula, executive director of the Kula Community Watershed Alliance, talks about the organization’s work to control invasive species in May. HJI / COLLEEN UECHI photo

Sara Tekula, executive director of the Kula Community Watershed Alliance, talks about the organization’s work to control invasive species in May. HJI / COLLEEN UECHI photo

So far they haven’t lost many plants, which Tekula attributes to being native species. She also sees it as proof of why the county needs to invest in watershed restoration while it pursues more wells.

There’s an old Hawaiian adage: “Hahai nō ka ua i ka ululāʻau,” the rain follows the forest, and Tekula said that still rings true. The less native forest and the more invasive species there are, the less rain, surface water and groundwater recharge there will be.

“To me, it’s not an isolated issue to just say, should we drill wells?” Tekula said. “It’s how are we creating a watershed that can sustain our island and sustain development at the rate that it’s happening?”