BIG UCSB PHYSICS NOBEL CELEBRATION

Every year in October our UCSB Physics faculty present an explanation of the Nobel Prize in Physics for that year. This year was different because two of the Nobel Prize winners were UCSB Physics faculty! Instead of others explaining the research, the actual winners took the stage. And it was a big stage: An overflow crowd at the UCSB Corwin Pavilion.

I was privileged to get a seat in the front as a UCSB Physics alumnus and as a media person. Here are my many photos from this privileged spot. Here are a few video clips I made.

WHY THIS NOBEL WAS GIVEN/WHY IT MATTERS

The prize-winning research involved pioneering work that led to current work on creating quantum computers. A very hot topic that is receiving billions of dollars now from big players like Google, Microsoft, IBM and Amazon, along with many smaller specialty players.

As explained during the UCSB event, much of the technology we enjoy today came as a result of decades of pure research in university laboratories. The benefits are not clear at the time. Long term thinking is needed. “Trump” was not named during the event. But all fingers were pointed at him with regard to his “chainsaw” destruction of funding for exactly this type of research. Executed in Trump’s so-called “Big Beautiful Bill”. We won’t see the resulting damage perhaps for decades.

Nobel Physics laureate Richard Feynman proposed the idea of a quantum computer in 1981. Primarily as a way to calculate or simulate quantum phenomena in physics. But other applications were soon envisioned. The problem: Making a quantum computer is fiendishly difficult!

WHO ARE THESE GUYS WHO WON?

The UCSB Physics Nobel winners in 2025 are John Martinis and Michel Devoret. They shared the prize with UC Berkeley professor John Clarke for work they did in the 1980s at Berkeley. Martinis was Clarke’s graduate student and Devoret was his post-doctoral student. Martinis went on to work at Google and on to newer commercial ventures applying this technology.

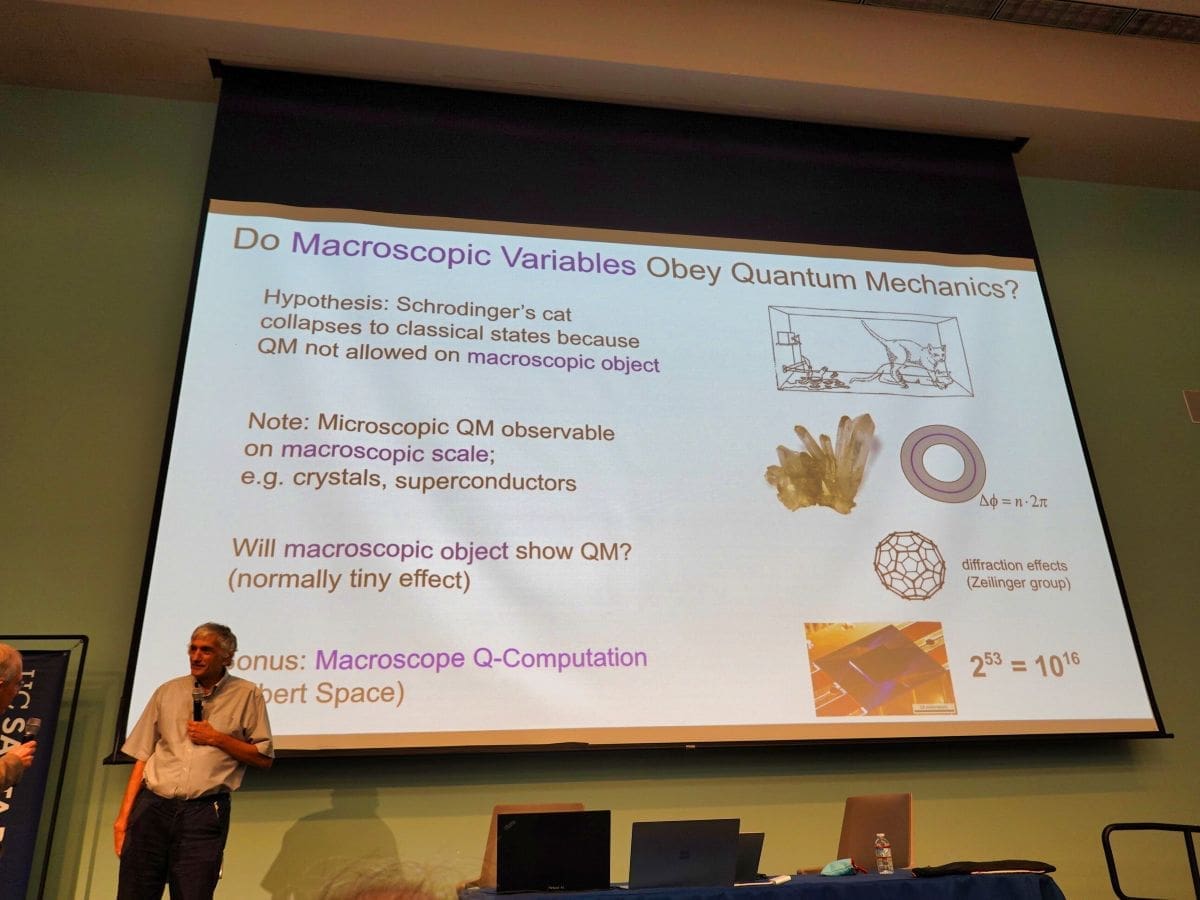

WHAT WERE THEY TRYING TO DO?

They were not thinking about quantum computing at the time. But they were thinking about solving one critical piece that would be needed for quantum computing: How to make a quantum mechanical system that operated on an every day scale. “Big enough to get one’s grubby fingers on” is the term they used in a “Science” article they published in 1988.

OUR EVERYDAY WORLD VS THE WEIRD QUANTUM WORLD

Ordinarily, quantum phenomena only are observed at the level of atoms and subatomic particles. A good thing, in some ways, because quantum phenomena are very weird and might make everyday life challenging!

For example, banks have vaults that can only be entered if you have the proper combination or key. In physics we would say that the walls of the vault are a “barrier” that cannot be penetrated.

But in quantum mechanics, no barrier is 100% solid. In principle, if you stand outside the bank vault, there is a small but finite probability that you might find yourself inside the vault! (There is a much larger but still infinitesimal probability that you find yourself embedded part way into the vault wall!)

But this probability is vanishingly small for people and bank vaults. You may have heard of “Schrödinger’s Cat”, which presents a similar mismatch of quantum phenomena to the everyday scale.

BRINGING THE WEIRD QUANTUM WORLD TO OUR EVERYDAY WORLD

The “CMD group” (Clarke, Martinis and Devoret) wanted to find something in between an atom and a cat or person to demonstrate quantum phenomena. Fortunately, earlier quantum pioneers offered tantalizing possibilities.

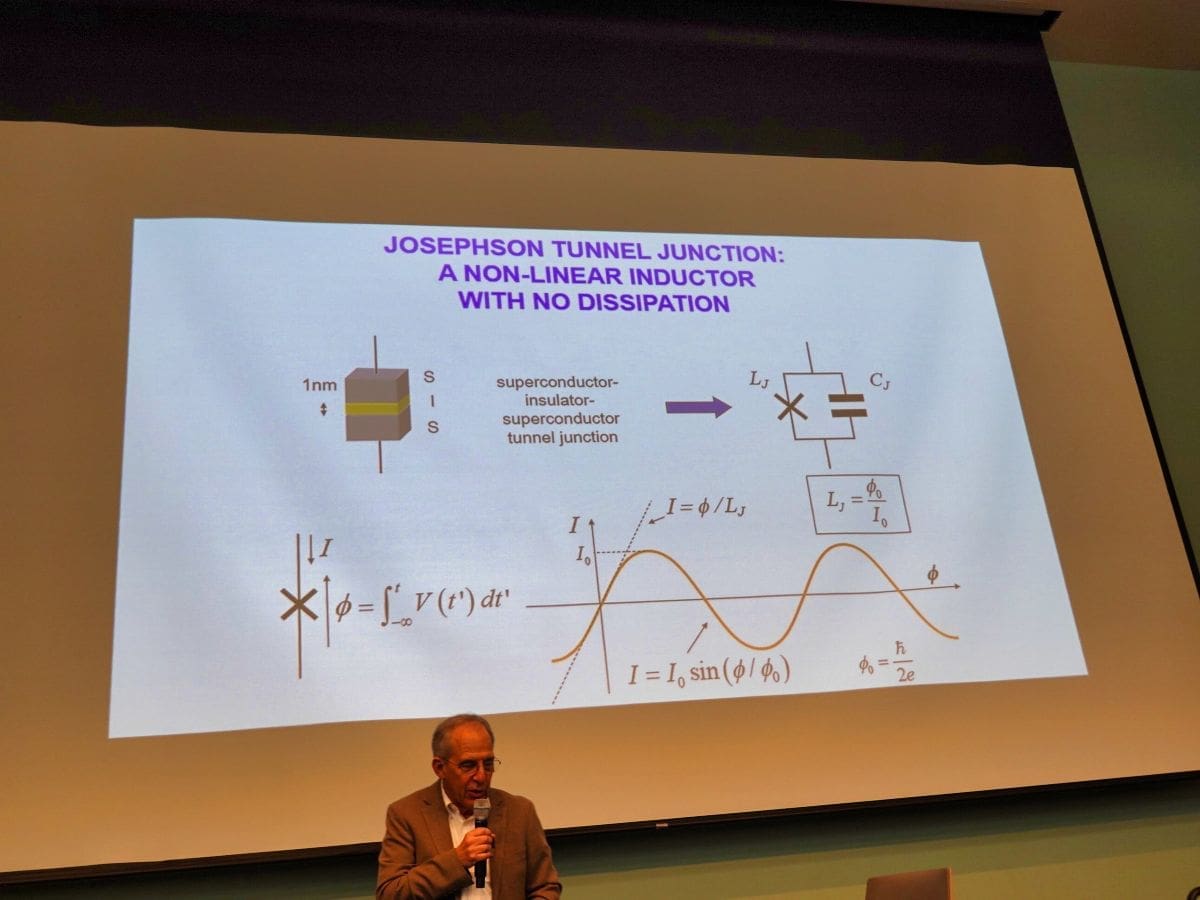

They credited physicist Anthony Leggett at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign for leading them to just the right device to study: The Josephson Junction. Brian Josephson shared the Nobel in Physics in 1973 for work he did as a 22 year old student at Cambridge University.

Josephson set up a barrier system like the bank vault wall as an electronic device we now call a Josephson Junction. It consists of two superconductors, separated by an insulating gap. Without quantum mechanics, there is no way for electrons to flow from one superconductor to the other across that gap.

But remember that quantum mechanics allows a small probability of the electrons penetrating that wall and continuing on their way. This is called “tunneling”.

(Full disclosure, thanks to my UCSB Physics mentor Virgil Elings, we had a very profitable business based on electron tunneling. In the form of Scanning Tunneling Microscopes and later Atomic Force Microscopes.)

This was a start to finding a finger-holdable quantum device, but there was much more to do. Individual electrons tunneling are cool, but CMD were looking for something larger.

CREATING SOMETHING BIG AND QUANTUM, BUT IT IS NOT SCHRODINGER’S CAT

I am grateful to a number of physicists for helping me understand what was special about what CMD achieved. UCSB Physics Chair David Stuart researches high energy particle physics. He explained to me that modern particle physicists don’t think of particles as being like tiny billiard balls. They think of them as being a “state” of a system.

David Stuart is the guy standing behind the podium, behind Devoret, in this photo. The gentleman in front of the podium is Physics professor Clifford Johnson.

CMD wanted to make something that acted like an atom, but that was much larger.

CONDUCTORS, SUPERCONDUCTORS AND SYNTHETIC PARTICLES: COOPER PAIRS

It is important first to understand how the superconductors in the Josephson Junction work. In regular conductors like copper, electrons flow fairly smoothly through the material and are barely attached to individual atoms. They act like a fluid in many ways. But this also means things don’t always flow perfectly smoothly. The electrons still have individual identities. They bump into each other and into the atoms of the conductor. The result is heat and energy loss. This is called electrical resistance.

Physicists Bardeen, Cooper, and Schrieffer won yet another Nobel Prize in Physics in 1972 for figuring out how superconductors avoid these imperfections of conductors. These superconducting materials had already been observed. They lose all resistance when they are cooled near absolute zero.

They figured out that in these materials, the electrons pair up into what we now call Cooper Pairs. These pairs act like a very different kind of synthetic particle than the individual electrons.

There are two kinds of basic particles: Fermions and Bosons. They are distinguished by an intrinsic property called “spin”. You can picture it as if they are little spinning balls, but of course in quantum mechanics nothing can really be pictured in such a way. Fermions have spins that are multiples of ½ and bosons have integer spins (0, 1, 2, etc). You may have heard of the famous Higgs Boson, which was in the news when the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva discovered it. Another Nobel Prize! (2013). (Yes, UCSB Physics was part of that discovery!)

When you put two spin ½ electrons together in a Cooper Pair, the combination acts like a single boson. And that makes all the difference in the world. Fermions are very fussy and avoid each other and bounce around, losing energy. But bosons are happy to coexist with each other and other things. Photons are spin 1 bosons. They can travel across space for billions of years and allow us to look at very distant stars and galaxies.

The Cooper Pairs merrily go on their way without bumping into things and creating heat and resistance.

THE “PARTICLE” IS THE STATE OF THE JOSEPHSON JUNCTION SYSTEM

Remember the Josephson Junction with that insulating gap? Well, the Cooper Pairs in the whole Josephson Junction get along so well that they effectively act like one single particle. In that loose sense of a particle being a single state.

And the two sides of the Josephson Junction (on either side of the barrier) are slightly out of phase with each other. Phase? Phase of what? Quantum mechanics is based on the Schrödinger Equation. And that is a wave equation in physics. CMD now had the “synthetic atom” they were looking for.

POKING AND PRODDING THE SYNTHETIC “ATOM”

But now they had to poke and prod it to see if this finger-holdable “atom” really acted quantum-mechanically.

That required two pokes and prods: Applying a “bias” current to the Josephson Junction. And zapping it with microwave energy.

QUANTUM SYSTEMS ONLY CAN TAKE ENERGY IN CERTAIN AMOUNTS

At this point I need to explain one more key concept. I very am very grateful to my physics friend Alex Bilmes, who works at Google. He used to be our neighbor and he very kindly came over for a soak in our condominium Jacuzzi for almost two hours as he explained this. I should note that Alex and I spotted each other across the vast expanse of Corwin Pavilion during the UCSB event! Here he was smiling at me from across the room.

Alex explained the difference between a quantum system and a “classical” system with regard to atoms and synthetic atoms. Think of a classical oscillating system like a pendulum or a swing. (Physicists call this a “harmonic oscillator”). If you are pushing someone on a swing, you can add any amount of energy you want. From a tiny nudge on up to a push so hard that it may push your friend all the way up and over. And they may not want to be your friend anymore!

But this is not the case with quantum systems like atoms. And that is a good thing. You may have pictured an atom as being like a tiny solar system. With the electrons orbiting the nucleus like planets orbiting the sun. But that can’t be right. It turns out that when electrons go in a circle, they radiate energy. It would be as if the planets are circling in water. They would slow down really fast! In the case of electrons classically orbiting, they would lose energy so fast that they would crash into the nucleus in about a millionth of a billionth of a second!

If that happened, there would be no interesting matter in the universe. Just a bunch of collapsed atoms that would all just collapse into neutron stars or black holes. No elements. No life. Boring.

Fortunately, quantum mechanics comes to the rescue. Unlike with the swing or the orbiting planets, atoms can only absorb or radiate energy in discrete allowed amounts. And that keeps the electrons from losing their energy and crashing. There is a lowest “orbital” and it doesn’t go any lower.

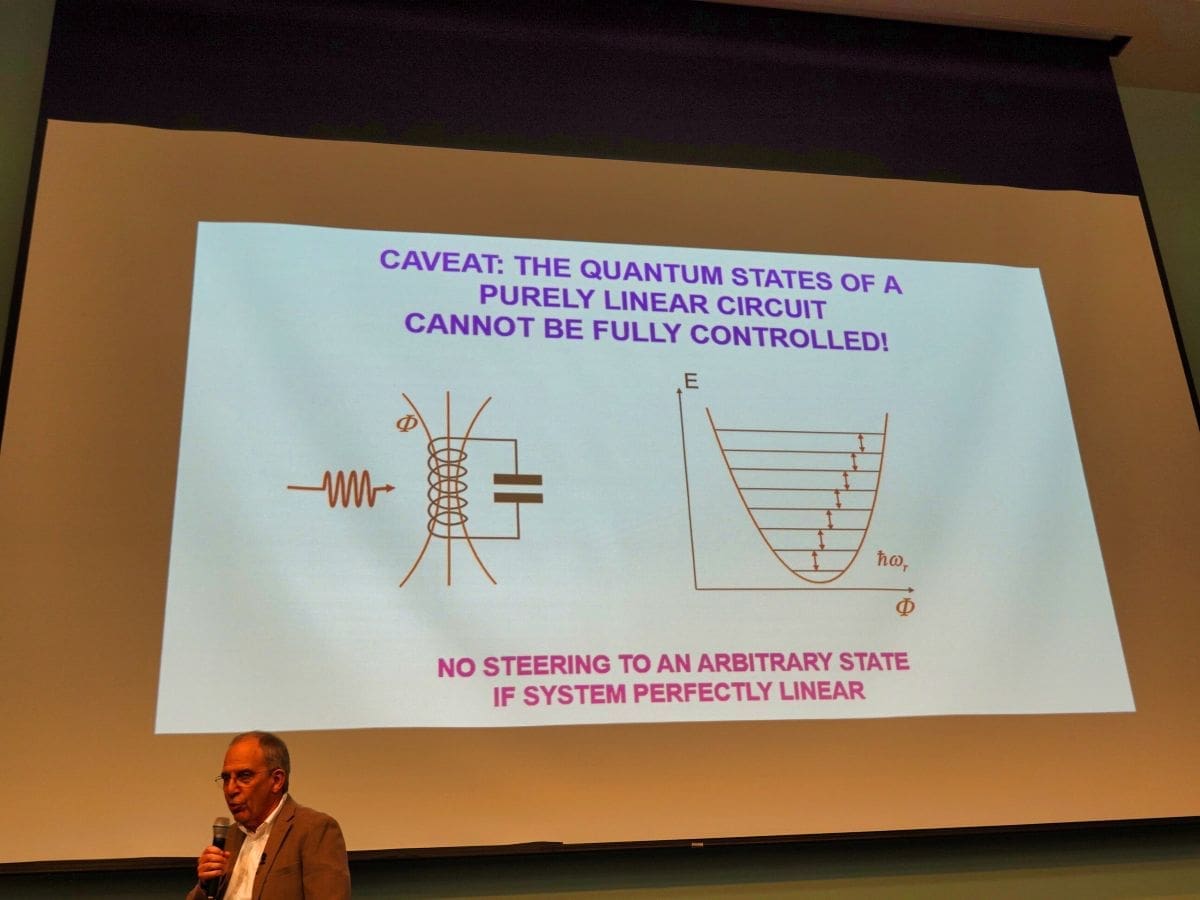

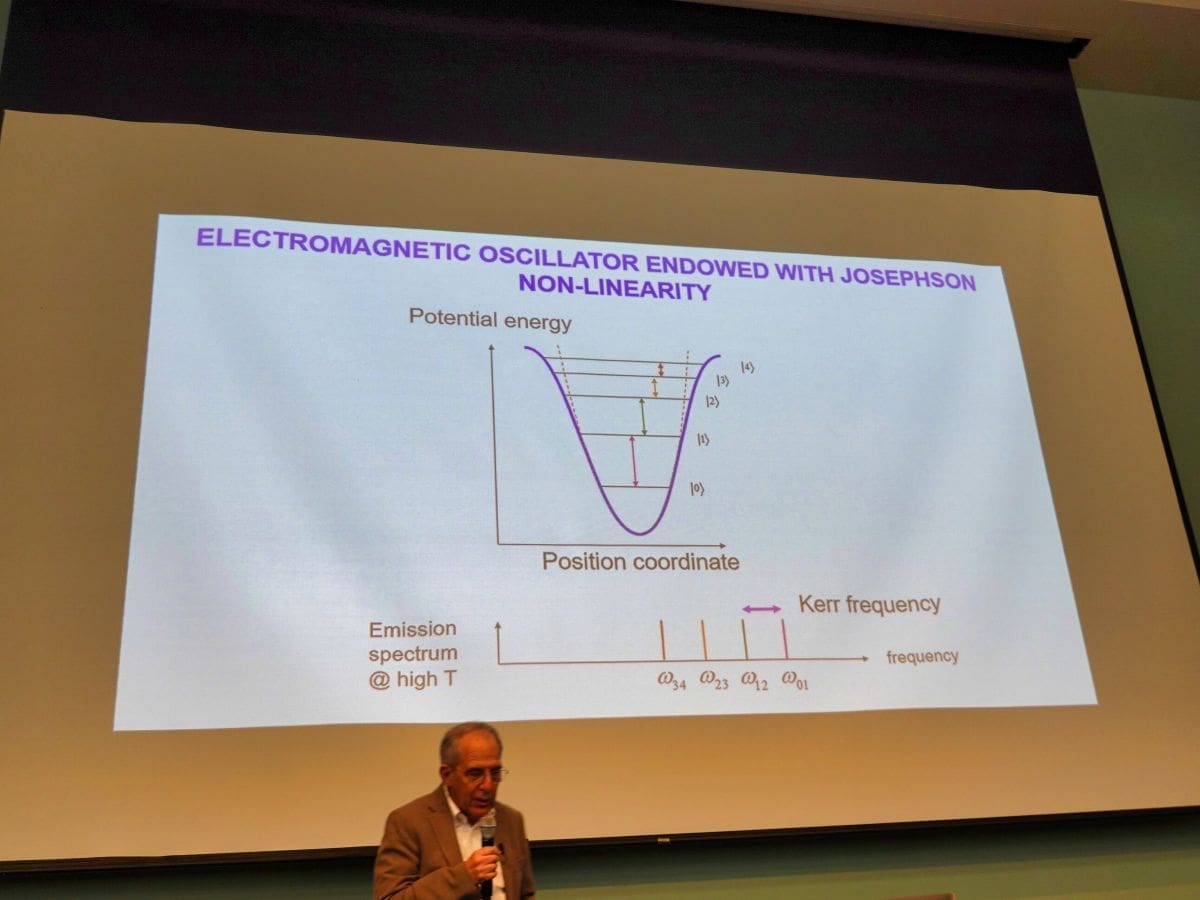

SYNTHETIC ATOM MUST BE QUANTIZED WITH UNEQUAL ENERGY LEVELS

So, Alex explained there are two things that make a simulated atom be like a real atom:

There have to be discrete energy levels that are “quantized”

Those energy levels can’t be equally spaced. We say that the system is “non-linear”

Here Devoret was explaining the non-linear bit.

The Josephson Junction system satisfies both of these requirements. But you have to give up picturing it as a literal particle or atom. You have to treat the entire system as being in a “state”. And that state depends on this phase between the two sides of the junction. And that in turn depends on how much voltage is applied. And how much energy is applied by zapping it with a microwave signal.

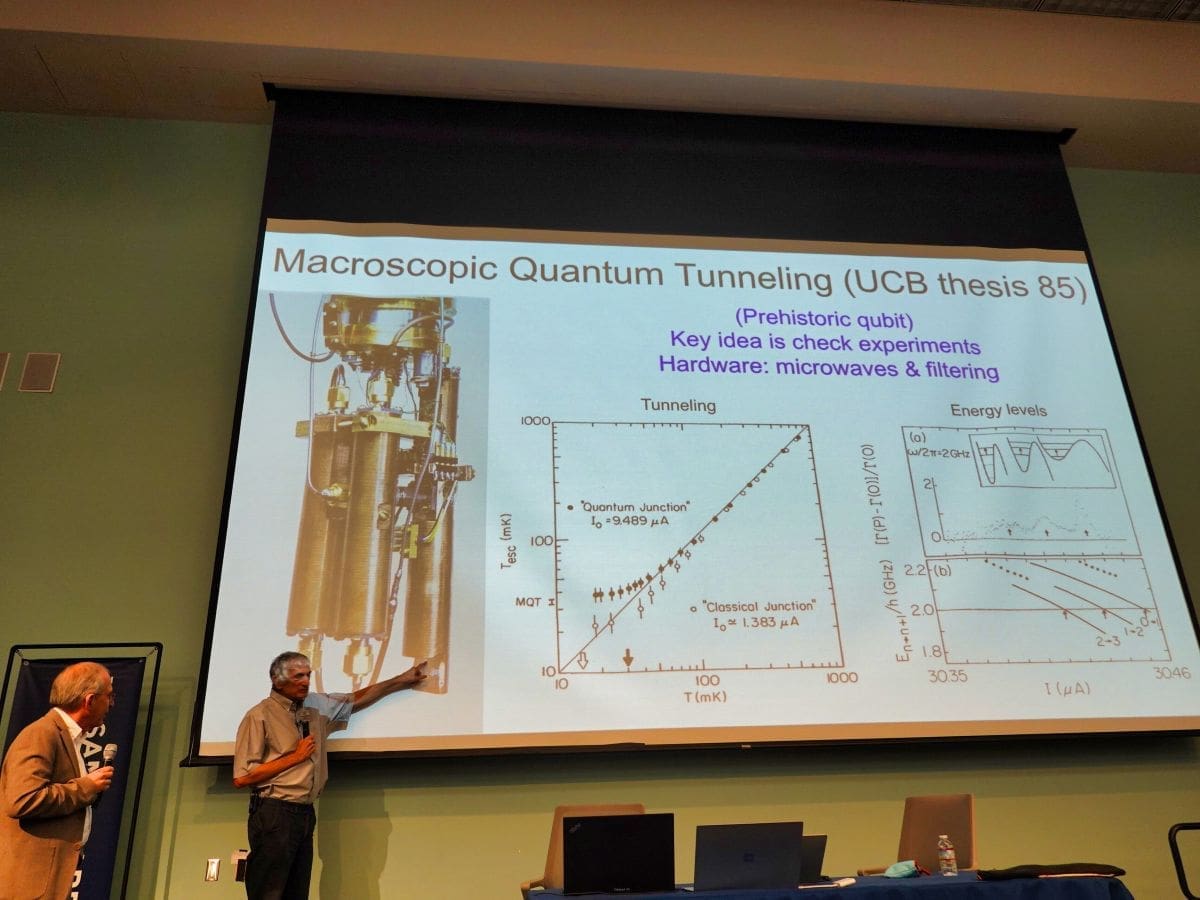

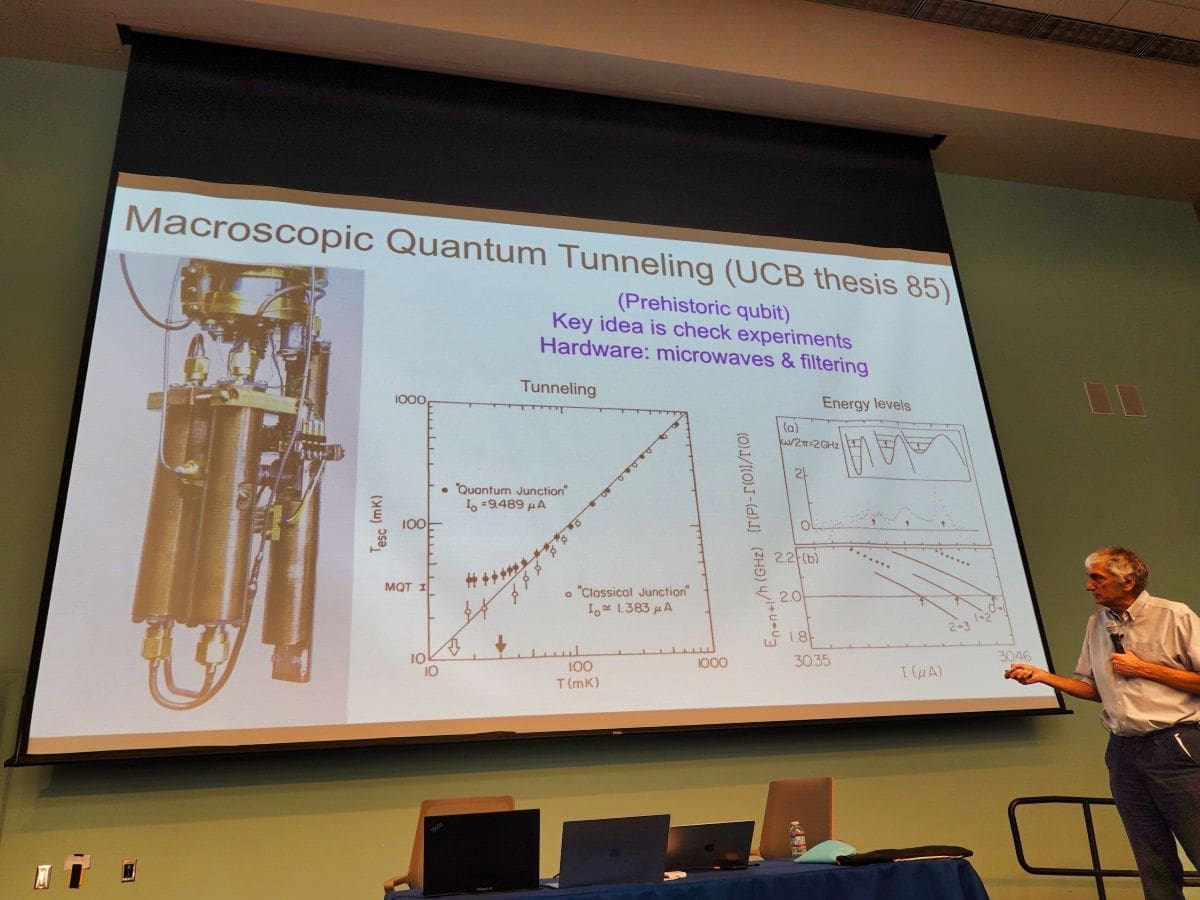

BUILDING THE APPARATUS

Quantum physics makes a very clear prediction of how the junction will behave if it is acting quantum-mechanically rather than classically. And that is the experiment CMD had to set up and perform.

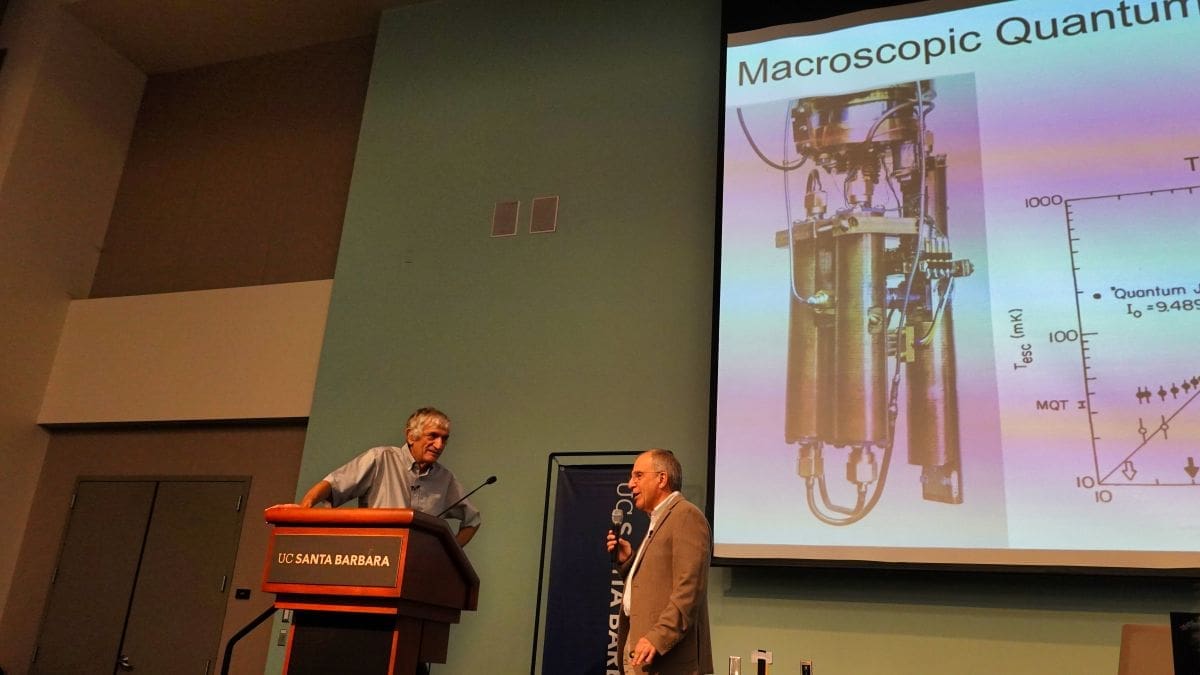

Here Martinis points to a photo of their apparatus as Devoret looks on. The diagram also shows the difference in the signal they are expecting if it behaves quantum-mechanically versus classically.

Here they took turns explaining the challenges of creating and operating this apparatus.

First of all, the superconducting materials they used had to be cooled to near absolute zero. But that was not enough. They also had to reduce the thermal noise even further. They used a copper powder filter to block such noise from sneaking in. In order to feed in the microwave signal, they needed a microwave type coaxial cable. Not something you can get from your cable TV store! Back then, everything had to be hand made from scratch.

Here Martinis is explaining these challenges.

Here Martinis reminded the audience that there were many smart physicists who said this could not work. They said that a “macroscopic” (everyday sized) system could not behave quantum-mechanically. Whether it is Schrödinger’s Cat or whether it is a Josephson Junction being tweaked in this odd way.

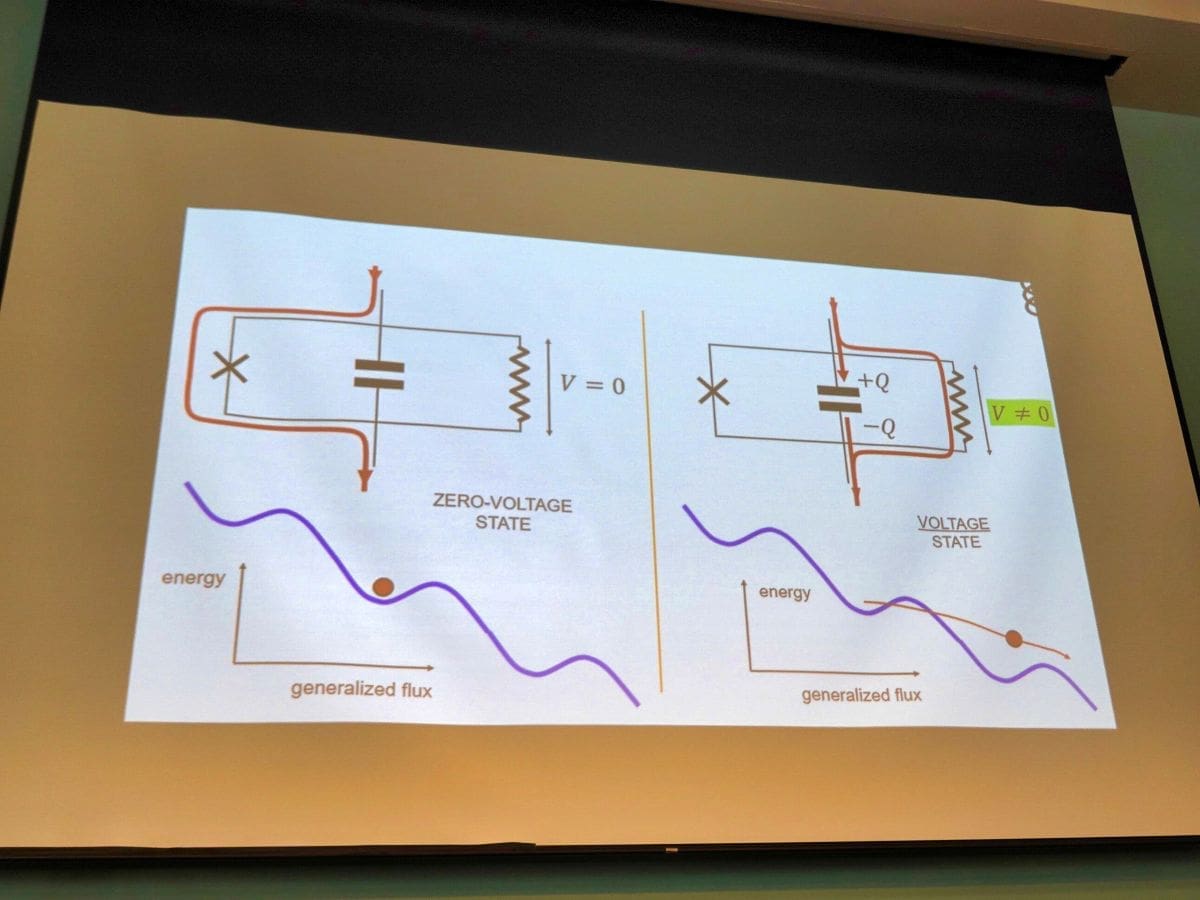

Here Devoret is showing how the Josephson Junction behaves when it is just sitting there minding its own business. That sine wave represents the energy barrier that is like the bank vault wall.

POKING AND PRODDING GIVES THE WEIRD QUANTUM RESULT

Applying a “bias current” tilts the energy barrier curve and allows the system (the state representing the virtual particle) to roll downhill. But it only rolls downhill when it is prodded with the microwave signal. And it needs a bit of quantum tunneling magic. When this happens, a distinct measurable voltage signal is observed.

And here Martinis is pointing to the results of their data. Showing that this system indeed behaved quantum-mechanically rather than classically. Forming a “prehistoric qubit” that could form a part of a quantum computer decades later! Success!

THEIR WORK GAVE US A WHOLE NEW WORLD OF TECHNOLOGY

Here Martinis is explaining how their early work led to over 1,000 good physicist jobs now in quantum computing. Something he is very proud to have been a part of creating.

QUESTIONS/ANSWERS/COMMENTS/CELEBRATION

After that, Martinis and Devoret took questions. Here they talked about how each of them got into physics, with some surprising twists and turns!

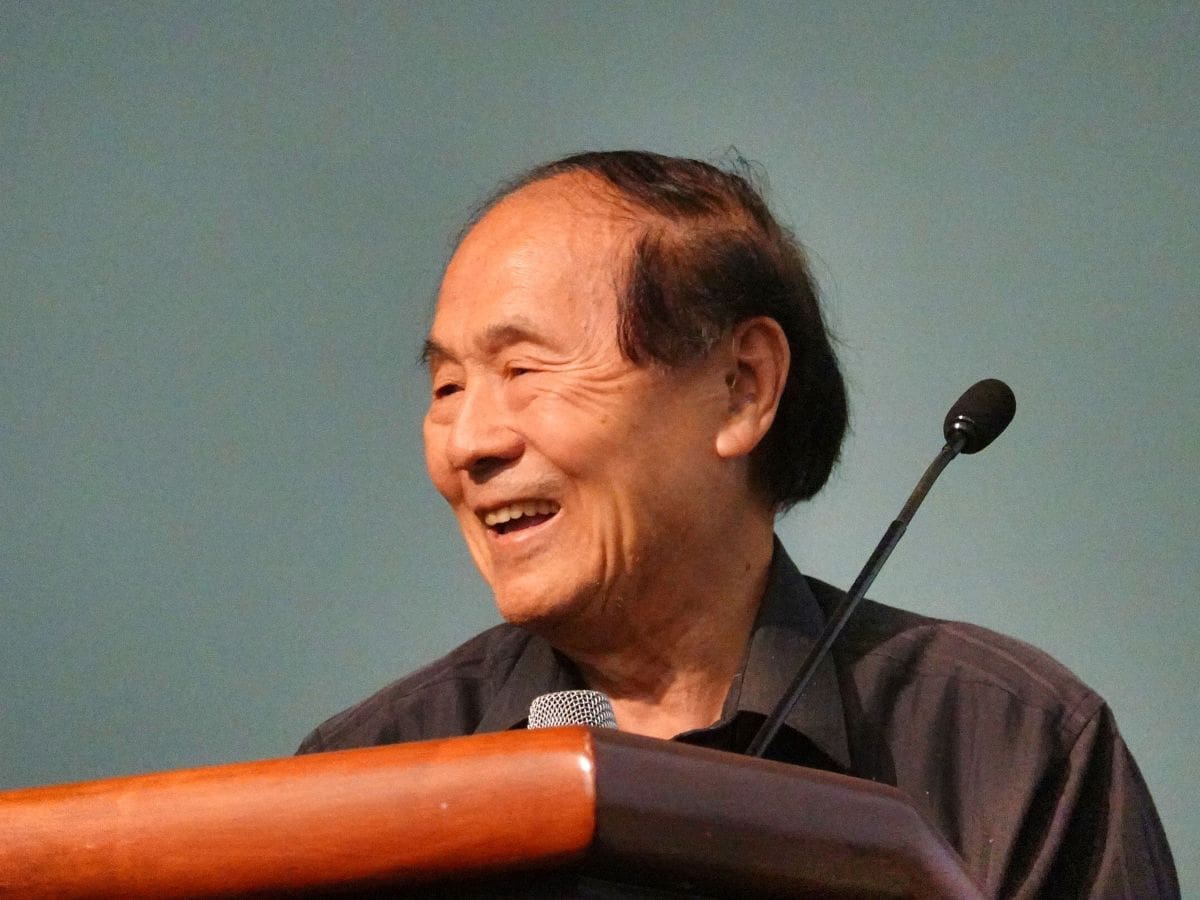

Former UCSB Chancellor Henry Yang recently stepped down as Chancellor after a record 31 years. He was on hand for the occasion.

The new Chancellor Dennis Assanis was honored to come to UCSB and preside over this event.

He also pointed out three other UCSB Physics Nobel Prize winners who were sitting up front. Here I photographed them before the event began. In the front row from left to right: Alan Heeger, David Gross, Shuji Nakamura

I was shocked when the crowd was asked to stand if they were currently UCSB Physics students and most of the people in the room stood up! The department was good when I was a student, but it has grown enormously in size and status and in sheer number of researchers and widely cited papers. By some measures, UCSB is the top physics research university in the world now!

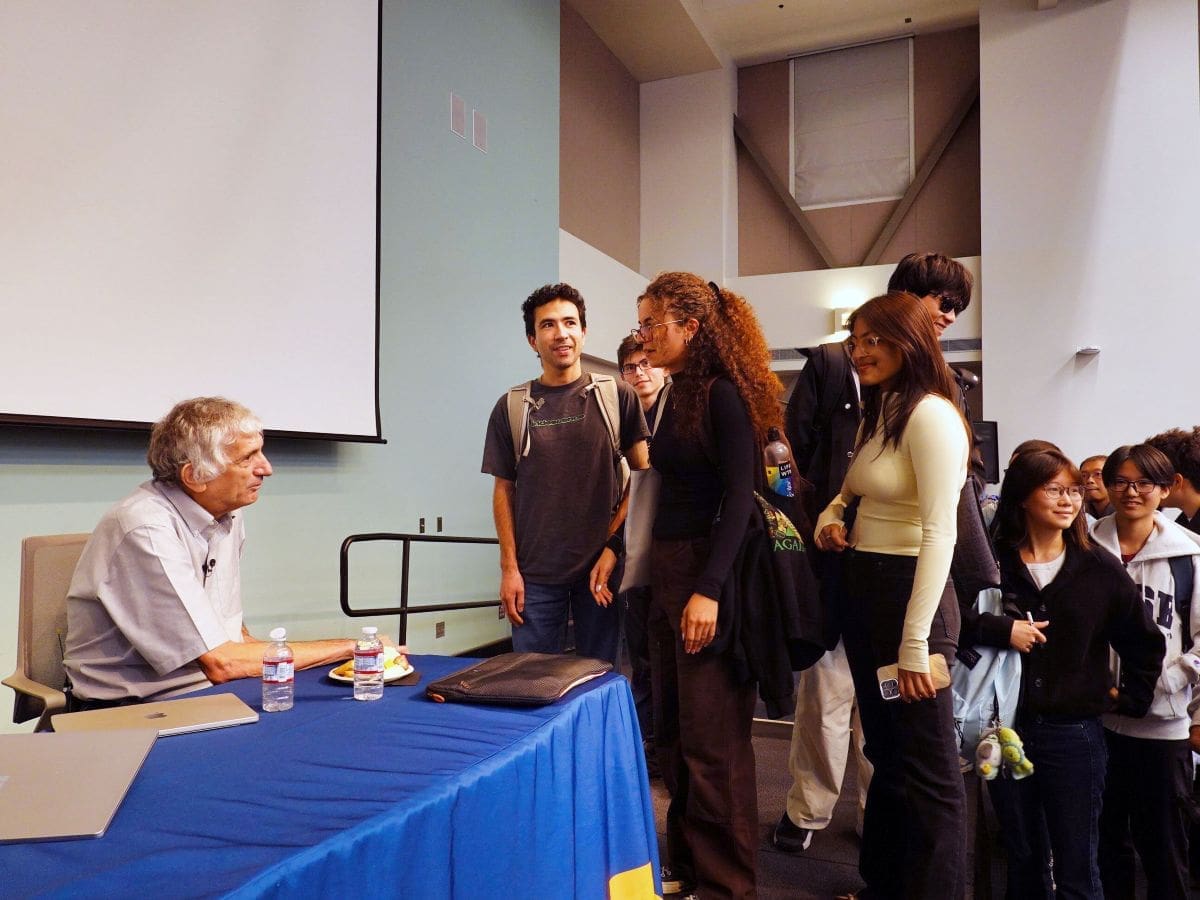

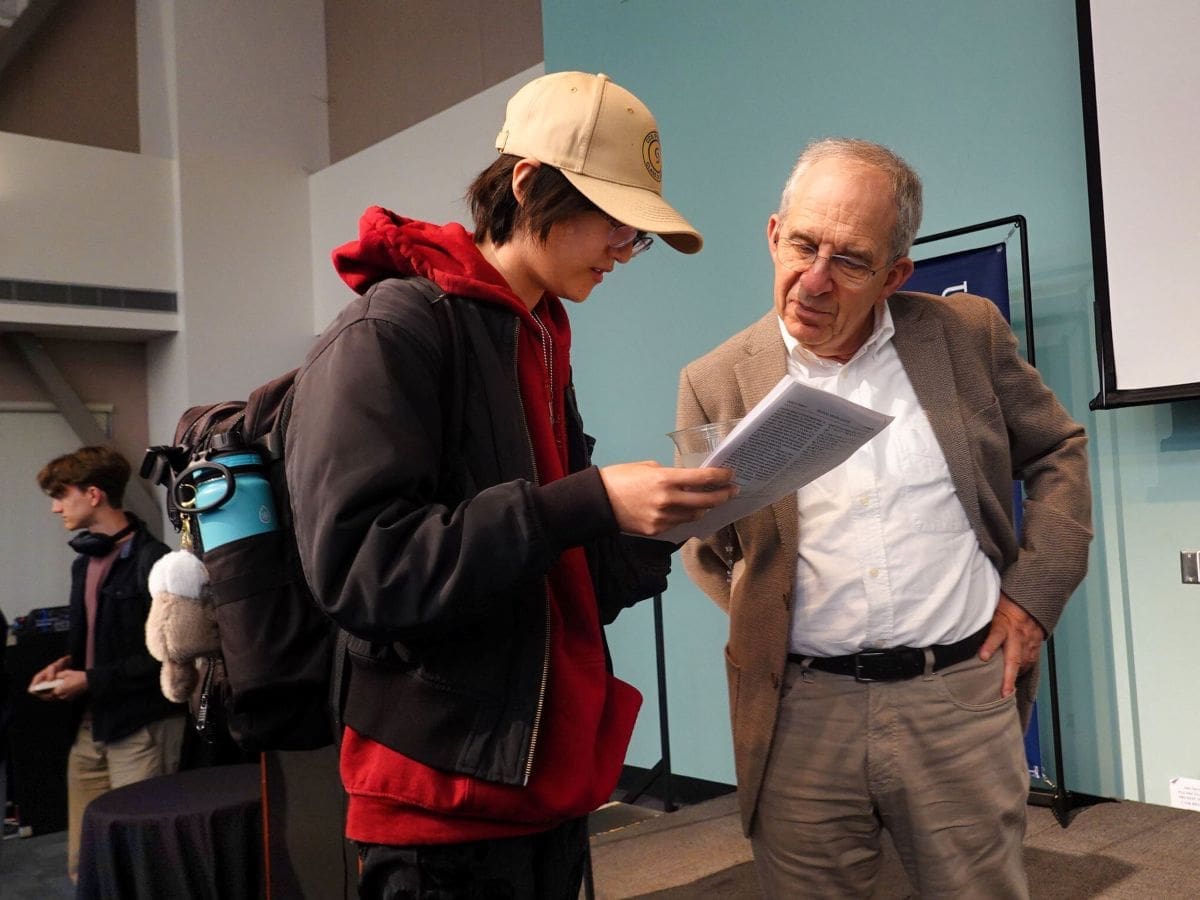

The event ended with a reception on the patio outside Corwin Pavilion. But Martinis and Devoret first attended to long lines of UCSB Physics students eager to talk to them.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

I should give thanks to one more physicist who helped me write this article: Lars Bildsten, who is the Director of the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics. (His architect wife Ellen Bildsten also comes on some of my hikes!). Lars very helpfully directed me to the information provided by the Nobel Committee that explained the details of this research. I had seen the press release, but missed noticing that it had links to more detailed information at a “Popular science background” level and at a “Scientific background” level. Here is that information!

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2025/press-release/