A series on the lengths some New Yorkers have gone to get their dream apartment.

Photo: Matthew Sedacca

Landing a good apartment in New York City can take some cunning. Or dumb luck. Or knowing a guy who knows a guy who just broke up with his girlfriend and needs someone to take over his West Village pre-war. In this new series, we’ll chronicle the lengths some New Yorkers have gone to get their perfect place.

Andrew Tesoro was sitting on the grass in Riverside Park when the idea came to him. Staring across the Hudson, the young architect imagined a helicopter lifting a trailer from a dinky New Jersey development and placing it on top of a building somewhere in Manhattan. “It was a fantasy,” he tells me, “but it was kind of a crystallization of the way I wanted to live in New York.” It was the late 1980s. Tesoro was more than a decade out of architecture school and had been running his own firm for a few years. The helicopter idea might not fly, but why not try building something of his own? He wanted a view and a place with some drama but also outdoor space and light. Getting that, even then, would require some finesse. But he had recently worked on a penthouse on Lexington Avenue that ended up being a crash course in development rights — on using the unused space above a building in order to build up. He knew that if he got himself a cheap-enough penthouse and bought the air rights, he could build himself a home in the sky. Friends called it a pipe dream. “It was an unusual thing to do at the time,” he tells me.

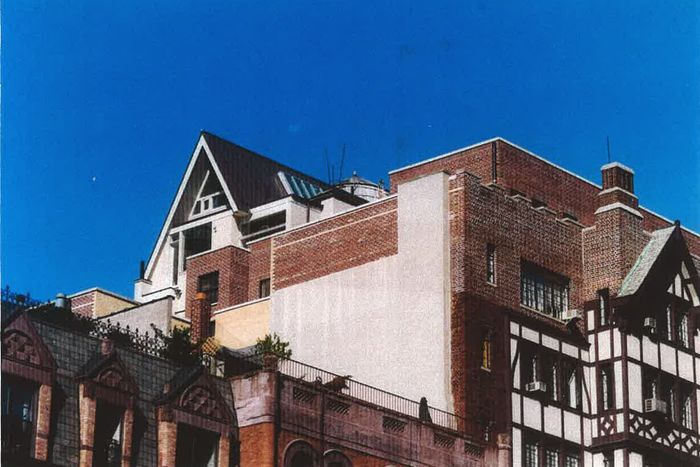

Tesoro spent years checking out Manhattan apartment buildings and townhouses for the perfect rooftop to build his penthouse unit.

Photo: Courtesy Andrew Tesoro

An issue with some rooftops he went to see was that the buildings’ mechanical equipment would make it awkward to build on them.

Photo: Courtesy Andrew Tesoro

Tesoro started scouting Manhattan rooftops in 1988 — he needed a top-floor unit and room to build. There were a few must-haves, including a roof terrace with a view and development rights for purchase. An apartment he checked out on West End Avenue looked out on the Hudson, but the rooftop’s layout would’ve required him to build a contorted, Z-shaped structure. “It was going to be awkward,” he remembers. There were a few four- and five-story brownstones he went to see with no elevator — impractical and a drag on his vision. The place he kept returning to again and again was 210 West 78th Street, a ten-story Tudor-style co-op built in 1926. Behind the building’s gabled façade sat a 400-square-foot penthouse apartment that was originally the super’s unit. It had a view of the Museum of Natural History and the East Side skyline, plus a proper elevator. Crucially, Tesoro also could work with the roof’s layout. The only problem was that the stubby little apartment was way out of his budget and way overpriced: The seller was asking $205,000, on top of roughly $1,000 in monthly maintenance. “I offered him $140,000, and he laughed at me,” Tesoro says. But he didn’t let up. By 1990, after two years of intermittent haggling, Tesoro finally got the seller down to $158,000 and managed to secure an agreement with the co-op to pay an additional $15,000 for the development rights he’d need to build upward. He was then off to the races. Well, almost.

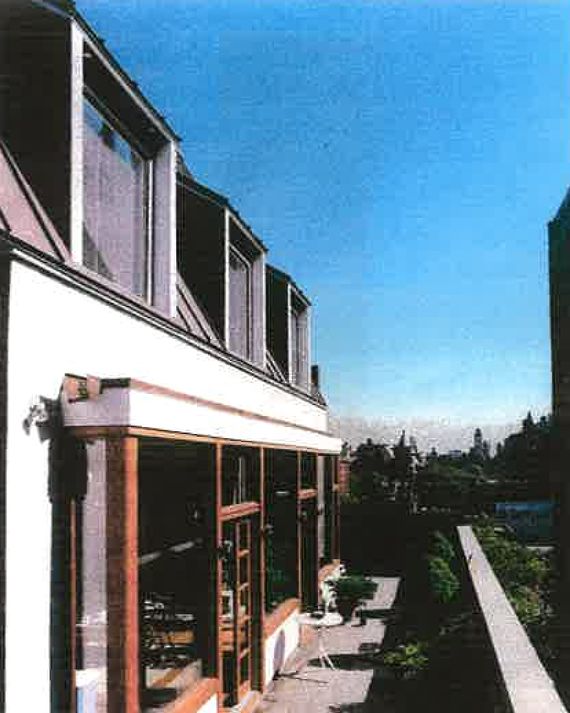

A rooftop terrace with a view was a must-have when Tesoro was looking for his perfect penthouse.

Photo: Courtesy Andrew Tesoro

Negotiating down the penthouse price had been a bit of a coup, but after the closing fees, Tesoro had practically nothing left in the bank for renovation costs. The recession that started in the summer of 1990 didn’t help. “My business was in a bit of a slump,” Tesoro says. (Plus, he adds, “I didn’t have the confidence to go into deep-shit debt.”) Things didn’t really start rebounding for him until at least 1993, so he made do with the studio as it was. “I thought, Oh my God, where’s the other room?”Tesoro’s partner, Joseph Uguccioni, says of the first time he saw the original unit. The place was small with a crappy little Pullman kitchen and a shower. But Tesoro made it work — he threw parties and guests got by sleeping on the floor. When the weather was right, he spent all of his time outside on his massive rooftop terrace, looking out on leafy treetops below. “I had all my meals outside,” he says. “I lived my life, basically.” It all sounds romantic, and it was in many ways, but he was also understandably getting impatient. Tesoro wanted to get on with building his dream. “I was, really, almost six years living in that one room, getting a little frustrated,” he says.

Plans showing Tesoro’s original duplex design for his penthouse at 210 West 78th Street.

Photo: Matthew Sedacca

By 1995, Tesoro was ready to knock down some walls. The co-op board had already given its blessing to the rough sketches he’d made of the penthouse (a large two-story box that, he says, was meant to showcase “an attitude about light and structure and spacemaking”). But by the time he had saved up enough cash to start, the Department of Buildings had stepped in with concerns. The penthouse was less than 30 feet from the property line, so the city wouldn’t let him expand the walls out any further. What he could do, though, was build an A-frame triplex with a sloped roof that stretched out past the first floor. “Legally, a roof can overhang in a backyard,” he says. After “many rounds of pleading,” city officials signed off. The penthouse would be three stories with dormers on the south side, a trio of bedrooms on the second floor, and a svelter third-floor attic. “I had to figure out something clever,” he tells me. “That’s how it ended up being a chalet.”

On the first day of demolition in 1996 — April Fool’s Day, Tesoro remembers — the contractor crew busted a water-supply pipe, flooding the three apartments below. (“I’m still a little superstitious about April 1,” he says). But maybe he just needed to get his bad luck out of the way up front: From there, the project more or less hummed along. The budget was tight so he used discards from other projects and Home Depot–grade fixtures to keep costs low. When the contractors built the second and third floors, they connected them with part of a fire escape Tesoro rescued from the former Gospel Tabernacle Church near Times Square, which he had worked on converting into a pizzeria. For the roof’s copper cladding, he sold the red 1995 Saab he had received as a bonus from a client. Just before the demolition began, Tesoro had moved into a nearby rental; after a year and a half of renovations though, he decided paying double rent was untenable. In the summer of 1997, he moved into the construction zone of his dreams. “There was no kitchen, no doors, zero railing,” he says. “But the bathrooms were functional, and the roof didn’t leak.”

Victor Tesoro and his friends growing up treated the three-story apartment like their own sprawling playground.

Photo: Courtesy Andrew Tesoro

As all of this house business was happening, Tesoro was also trying to plan for the rest of his life. “I wanted a place where I would be able to start a family,” he says. For a gay man in his 40s in New York City, “it was not a straight path.” Tesoro adopted his son, Victor, in 2000. Uguccioni moved in soon after. The home was still far from complete. And maybe Tesoro was a little lax on childproofing, like waving off putting a railing on the temporary stairwell between the first and second floor. “The moms and babysitters were a little nervous,” he says. (Uguccioni was too, at first.) “For the kids, it didn’t matter,” Tesoro says. Victor, now 25 and living in Ithaca, loved it. He tells me about racing with his friends up and down the steps and having Nerf-gun fights — as if the house were their playground. (One ground rule, he remembers, was no climbing on the water tower behind the penthouse.) Victor also made sure everyone knew they were stepping into his dad’s magnum opus. “I was really proud of him,” he says. “Whenever my friends would come over, I’d be like, ‘My dad designed this.’” The roof terrace became a spot to splash around in a mini-pool, and where the couple hosted barbecues with other families and held a bar mitzvah for Victor. “Kids liked coming over here,” Tesoro says. “And I loved the kids.”

Decades later, Tesoro says his dream home still isn’t quite finished.

Photo: Matthew Sedacca

Tesoro kept working on the chalet in fits and starts. A friend built the ash cabinets that still line his open-concept kitchen, and his mom and sister helped him pick out brand new stainless appliances. But even 30 years after he started his grand renovation, the space still looks very much like it’s a work-in-progress: An electric line is hanging out of the wall for a light that hasn’t been selected, and the closet doors still have yet to be installed (a rod and curtain from Amazon is blocking off one on the first for now). “I’m very much the case of the shoemaker whose kids go without shoes,” he says. The third floor, with its four exposures and massive skylight, was supposed to be a “wintertime terrace” and studio where Tesoro could paint. Instead, it’s become a de facto storage space, where things like Victor’s surfboard and a small gallery’s worth of paintings catch the morning sun.

Tesoro, now in his early 70s, still has an eternally evolving to-do list, which includes replacing the kitchen’s beat-up Home Depot countertops with stone and installing the new sink faucet that’s been sitting in its box for years. There have been a few leaks, and patches of the raw Sheetrock still need to be painted. It’d be nice to finally have actual doors for the closets, too. “People say, ‘Oh, you could sell that apartment for millions,’ and it’s probably true,” he says. “But if I love living here, then why?”

Location: 210 West 78th Street

Costs: $158,000 for the unit, plus $15,000 for the air rights in 1990. About $200,000 for initial construction plus “several hundred thousand dollars” in additional construction and repairs.

Maintenance: currently more than $3,300

Years Lived There: 35

Greatest Disappointment: When Tesoro finished construction on his penthouse, he had views in all four directions from his third floor. Since then, residential skyscrapers have gone up around his unit, effectively blocking all but the eastern view of the apartment. “We used to be able to, from the corner of the roof, see the Empire State Building,” Tesoro says. “We used to wave to our friends walking along Broadway.”

Favorite Part: The rooftop terrace. “The part that didn’t get built on,” Tesoro says.

The penthouse is something of a local curiosity. Joseph Uguccione recalls once shouting from his balcony to people across the street who wanted to know about his unusually shaped home.

Photo: Courtesy Andrew Tesoro

Tesoro stripped the front door to reveal the decades-old metal frame.

Photo: Matthew Sedacca

Victor Tesoro tells me that he always told his friends who came over that they were stepping into his dad’s own creation.

Photo: Courtesy Andrew Tesoro

The stairway connecting the apartment’s second and third floors of was once part of the fire escape for the former Gospel Tabernacle Church in Times Square (now John’s Pizzeria).

Photo: Matthew Sedacca

Tesoro says he broke up the glass window into segments rather than one large triangular piece so it could fit in the building elevator.

Photo: Matthew Sedacca

Tesoro says he isn’t too worried about losing his eastern view because it looks out on a landmarked block.

Photo: Matthew Sedacca

Related