For the first time, scientists have produced a 3D temperature map of the ultra-hot exoplanet WASP-18b, a gas giant that is so hot it can tear apart water molecules. This breakthrough, achieved using data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, provides an unprecedented look at how temperature varies across the planet’s surface, revealing extreme heat zones and cooler regions where water vapor still exists.

WASP-18b, a planet nearly 10 times the mass of Jupiter, orbits its star at an astounding speed, completing a full rotation every 23 hours. Positioned just 400 light-years away from Earth, the planet experiences temperatures so high on its sun-facing side that they can break down water vapor. This makes WASP-18b an ideal target for astronomers looking to study the impacts of extreme heat on planetary atmospheres.

Mapping the Unseen: A New Era for Exoplanet Research

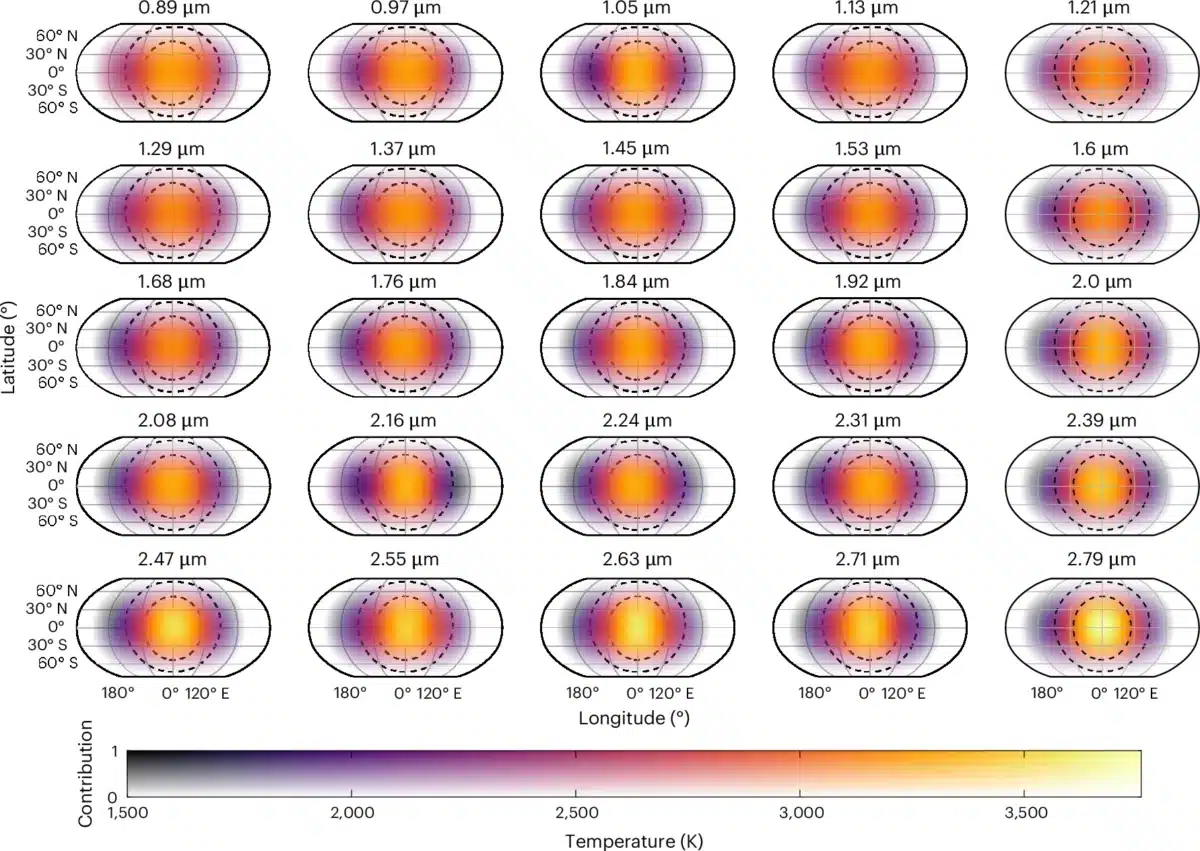

The creation of the 3D temperature map of WASP-18b marks a significant leap in our understanding of distant worlds. Traditionally, astronomers could only estimate the average temperature of exoplanets, but this new approach allows for a detailed view of temperature distribution across the planet’s surface, extending from pole to pole and top to bottom.

This breakthrough was made possible by a technique called “eclipse mapping,” which ” allows us to image exoplanets that we can’t see directly, because their host stars are too bright,” said Ryan Challener, a postdoctoral associate at Cornell University.

According to the full study published in Nature Astronomy, this method can distinguish between areas where water vapor is present and areas where it has been broken down by intense heat, allowing for the construction of a detailed 3D map.

A team of Astronomers used the #JWST to create the first 3D atmospheric map of exoplanet, WASP-18b, located 400 lightyears from Earth.

WASP-18b is massive “ultra-hot jupiter”, revealed striking temperature contrasts, including regions so hot that water molecules are destroyed. pic.twitter.com/R7a3EYFtQx

— Trentymus Kostorus (@TrentKostorus) November 4, 2025

A Planet Where Water Doesn’t Stand a Chance

WASP-18b is often described as an “ultra-hot Jupiter” due to its extreme temperatures. The planet’s dayside, which constantly faces its star, reaches temperatures that soar close to 5,000°F, hot enough to break apart water vapor. In fact, scientists had long predicted that the heat on such planets would destroy water molecules, but this new map has confirmed that the process occurs on a global scale.

The map revealed a super-hot core directly facing the star, surrounded by a cooler zone where more water vapor could still exist. This observation aligns with the hypothesis that planets with extreme heat would lack water, while cooler regions would retain it.

According to Megan Weiner Mansfield, an assistant professor of astronomy at the University of Maryland, this is the first time scientists have been able to observe the temperature gradient that shows this phenomenon across a single planet’s atmosphere.

The colors represent temperature, and the transparency indicates the contribution to the observed flux, based on the angle between the point on the map and the observer’s line of sight. Credit: Nature astronomy

The colors represent temperature, and the transparency indicates the contribution to the observed flux, based on the angle between the point on the map and the observer’s line of sight. Credit: Nature astronomy

Studying Exoplanet Atmospheres Like Never Before

While the extreme heat of WASP-18b made it an ideal subject, scientists are now eager to apply this method to smaller, rocky planets and even those without atmospheres. By analyzing temperature variations, researchers can uncover valuable insights into the composition and conditions of these worlds.

“It’s very exciting to finally have the tools to map the temperatures of distant planets in this much detail. It sets us up to possibly use the technique on other types of exoplanets,” noted Mansfield.

For astronomers, the ability to analyze temperature data in three dimensions: latitude, longitude, and altitude. As pointed out by Megan Weiner Mansfield, this breakthrough enables far more precise comparisons between distant exoplanets and those in our own solar system.