Photo-Illustration: Intelligencer; Photo: Amazon

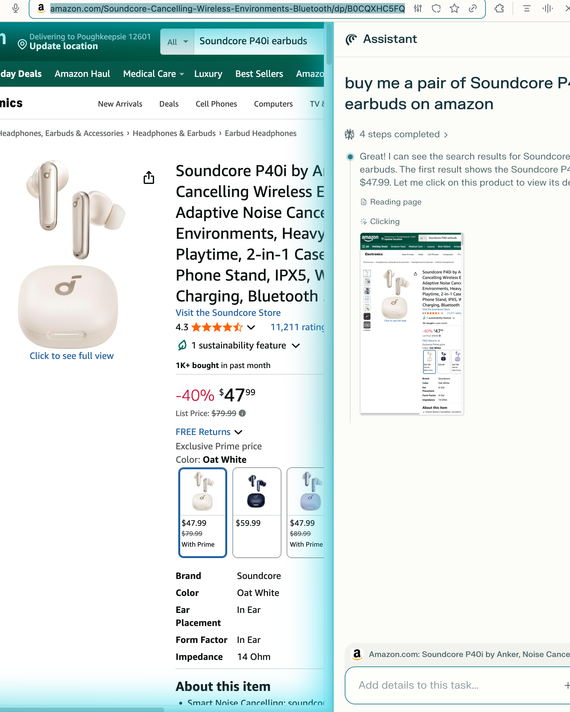

Right now, if you want, you can download a web browser called Comet, made by AI-search company Perplexity, and tell it to shop for you. You might type, for example, “Buy me [a specific earbud] on Amazon,” after which it will open a tab, navigate to Amazon.com, enter your search in the box, and attempt to find and click the buttons necessary to add it to your cart. (A browser from OpenAI, Atlas, will do the same thing, as will a few others.) Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t, and it’s not clear why many people would want to use such a feature now, in its current state. But it’s a pretty good demonstration of new AI capabilities as well as a statement of intent: AI companies, using “agents,” want to try to do more things on behalf of their users — research, shopping, work — and see the browser as a way to get there.

It’s interesting to watch a self-clicking browser work, but software like Comet and Atlas — along with other less showy AI agents — also poses an obvious question: What about all that stuff that’s getting clicked on? AI companies are suggesting that their browsers will soon be able to interact with websites on your behalf. Won’t the people and companies that run those websites, which were designed for use and patronage by humans, have issues with the automation of their visitors, customers, clients, or employees?

This week, Amazon answered clearly in the affirmative, in the form of a lawsuit against Perplexity. The language is spicy:

Amazon brings this action to stop Perplexity AI, Inc.’s (“Perplexity” or “Defendant”) persistent, covert, and unauthorized access into Amazon’s protected computer systems in violation of federal and California computer fraud and abuse statutes. This case is not about stifling innovation; it is about unauthorized access and trespass. It is about a company that, after repeated notice, chose to disguise an automated “agentic” browser as a human user, to evade Amazon’s technological barriers, and to access private customer accounts without Amazon’s permission.

Fraud! Abuse! Trespass! Evasion! This is a threatening lawsuit — it later refers to Perplexity as an “intruder” — but it’s also a useful window into Amazon’s thinking on AI and where its business fits into a theoretical world where more people do more things with chatbots and agents. It might not be right to say the company is worried, exactly. But it’s certainly clear about what it doesn’t want to happen, which happens to be precisely what some AI companies clearly want.

Photo: Amazon

“AI that can do a bunch of stuff for you” is one of the outcomes implied and demanded by the AI industry’s massive valuations and infrastructure investment, alongside (and connected to) “AI that can replace workers,” “AI that can do science,” and, perhaps most imminently and realistically, “AI that can command a lot of your attention.” Apps like Comet and OpenAI Atlas see the browser, where people spend a lot of time and do a lot of stuff, as a sort of mega-loophole: not just a shortcut to testing out their models on real-world tasks, but also a way to get fairly complete access to users’ digital lives without asking them for all their passwords or working directly with other companies (Comet’s Amazon trick works because users’ browsers are probably already logged into Amazon).

It’s easy to see why Amazon might not be thrilled about another company building a bot that can navigate its site and automate the buying process. In a narrow competitive sense, it has a new AI interface of its own, the chatbot Rufus, which Amazon customers can use instead of search. More generally, Amazon isn’t interested in letting a third party take over the experience of using Amazon, which is important to the company in a lot of different ways: It defines customers’ relationship to and perception of the company; it gives them the power to control and direct the attention of users and sellers; it has allowed them to build an advertising business that, while making the site generally more annoying to use, also makes the company a lot of money.

Most broadly, AI companies are hoping to end up in a situation where their products are the default interface for all sorts of things, and browser agents represent a small but aggressive move in that direction. A world where all purchases flow entirely through another company’s interface, chatbot or otherwise, is something that Amazon would prefer to avoid, or at least have a say in, which is perhaps why the company’s lawyers are talking about Perplexity as if it’s built an automated ticket-scalping app, a sneaker-sniping bot, a data scraper, a data-exfiltration tool, or rip-off interface for its product catalogue. Earlier this week, Perplexity argued on its site:

Amazon wants to block you from using your own AI assistant to shop on their platform … Amazon should love this. Easier shopping means more transactions and happier customers. But Amazon doesn’t care. They’re more interested in serving you ads, sponsored results, and influencing your purchasing decisions with upsells and confusing offers.

Suggesting that “Amazon should love this” and then describing the ways that it might cause them to make less money is sort of funny, but between the lawsuit and Perplexity’s response we can get a pretty clear sense of what’s going on here: an attempt by Amazon to stop a marginal player from setting a precedent it doesn’t want, and a clear signal to bigger ones — OpenAI, Google, and other firms Amazon already competes and partners with — that, if they want their tools to touch Amazon, they’ll have to do it on Amazon’s terms.

This is a sort of conflict we can expect to see a lot of, and soon. As AI companies (with the consent of their customers) unilaterally send agentic tools out onto the web, everyone else is going to have to figure out how to respond. Do they just let it happen? Encourage it? Build their own? Do they see traffic from agents as a sign that they need to partner with AI firms, or maybe that they should shut them out entirely? How this resolves may depend less on what these models are capable of, and what outside services want, than on emerging user habits; if enough chatbot users get used to shopping inside a chatlike interface, away from e-commerce platforms and search engines, then companies like Amazon might have to accommodate a new reality. For now, though, they’re eager to keep control.

Sign Up for John Herrman column alerts

Get an email alert as soon as a new article publishes.

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice