A new study has uncovered how exoplanets, orbiting too close to their stars to retain water, are surprisingly water-rich. Researchers discovered that these worlds, called sub-Neptunes, are generating their own water deep inside, challenging earlier theories on how planets form and maintain liquid water.

Temperatures near these stars should have been too high for water to survive. Yet, observations from NASA’s Kepler mission revealed that some of these cosmic bodies still appear to be covered in vast amounts of water.

The Secret of Water-Rich Worlds

According to the study, published in Nature, led by researchers from Arizona State University and supported by teams from the Open University of Israel and the University of Chicago, sub-Neptunes may be producing water on their own.

Traditional theories about planetary water focus on two possibilities: either water is delivered to planets via comet or asteroid impacts, or planets form further from their stars and gradually migrate inward. However, these theories fall short when explaining the abundance of water found on planets much closer to their stars.

The new research presents a different explanation. Rather than relying on external delivery, these celestial bodies could be generating their own water through chemical reactions within their rocky cores. The study’s authors found that under extreme pressure and temperature, hydrogen from the sphere’s atmosphere reacts with minerals in the core to produce water. This process occurs deep inside the planet, at the boundary between its rocky core and hydrogen-rich atmosphere.

The first image ever taken of an exoplanet was published #OTD in 2004. It shows a giant planet, called 2M1207b, approximately five times the mass of Jupiter, that is gravitationally bound to a young brown dwarf, approximately 170 light-years from Earth. pic.twitter.com/luQsaw5ptx

— Beyond Earth (@Andrzej75651576) September 10, 2023

Lab Breakthroughs: Water on Exoplanets

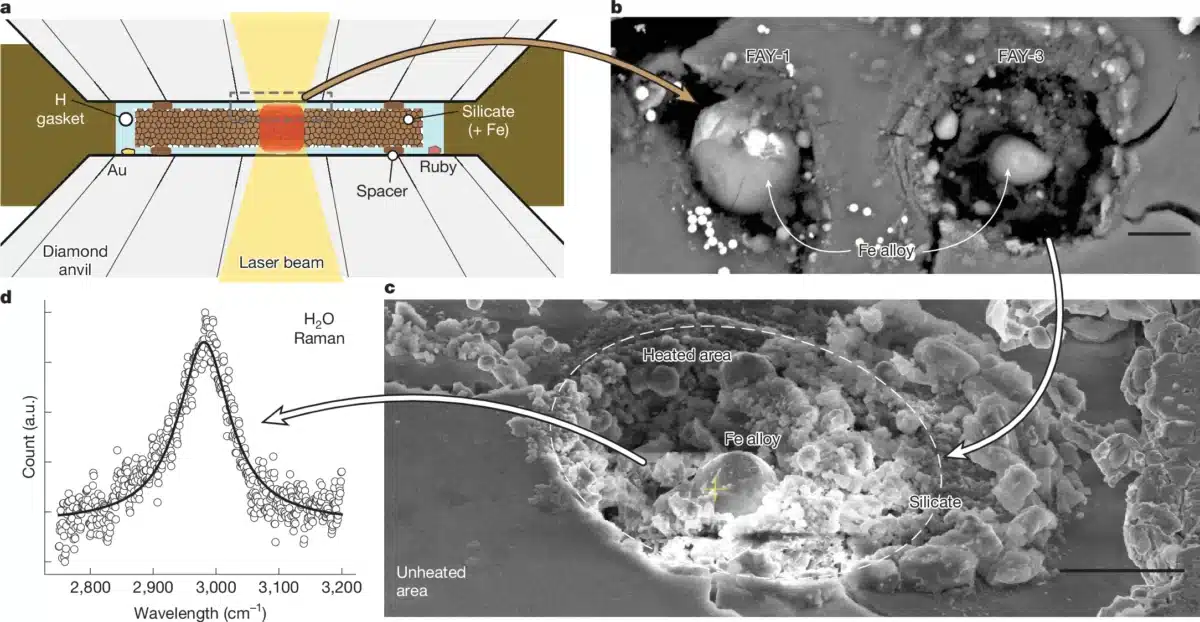

To understand how this happens, the research team used cutting-edge experiments at the University of Chicago’s Advanced Photon Source synchrotron facility. Using diamond-anvil cells to simulate the intense conditions inside sub-Neptunes, they subjected rock samples to pressures 10,000 times greater than Earth’s atmospheric pressure and temperatures above 3,000 degrees Kelvin. Under these conditions, the researchers discovered that:

“oxygen liberated from the silicate melt reacts with hydrogen, producing an appreciable amount of water up to a few tens of weight per cent, which is much greater than previously predicted.”

These reactions occur far more efficiently under the extreme pressures inside these heavenly bodies than they would in low-pressure conditions. The findings suggest that sub-Neptunes are capable of creating water over billions of years through these internal processes.

Laser-heating of silicate melts in a hydrogen setting using a diamond anvil cell. Credit: Nature

Laser-heating of silicate melts in a hydrogen setting using a diamond anvil cell. Credit: Nature

Shifting the Search for Habitable Planets

If sub-Neptunes can generate their own water, the likelihood of discovering water-rich exoplanets increases significantly. This broadens the potential for identifying worlds that may have the conditions necessary to support life, as water is a crucial element for biological processes. The study also implies that sub-Neptunes may not be vastly different from other exoplanet types, but rather represent an early stage in the development of water-rich worlds.