An international team of astronomers has identified a rare, potentially habitable super-Earth just 19.5 light-years from Earth. Named GJ 251 c, the planet orbits within the habitable zone of its parent star—a narrow region where temperatures may permit liquid water. It is the closest planet of its kind found to date and, critically, among the few that may be observable in detail using next-generation telescopes.

The discovery, led by Corey Beard and published in the Astronomical Journal, presents a powerful new case for the direct imaging of rocky exoplanets. With the 30-meter-class telescopes expected to come online within the decade, GJ 251 c could become the first non-transiting, potentially habitable planet to have its atmosphere directly analyzed.

This find is not speculative. It is grounded in over two decades of radial velocity data from some of the world’s most advanced instruments, including HPF, NEID, and archival datasets from Keck/HIRES, SPIRou, and CARMENES. GJ 251 c is now considered the top northern sky candidate for terrestrial planet imaging via reflected light.

The broader significance lies not just in the planet’s potential habitability, but in its accessibility. As Beard and co-authors write,

“GJ 251 c falls in a very narrow range of parameter space wherein a terrestrial, HZ exoplanet may be directly imaged via reflected light with the upcoming next generation of extremely large telescopes (ELTs).“

Twenty Years of Data Reveal a Hidden Second World

The host star, GJ 251, is a relatively quiet M3 red dwarf located just 5.58 parsecs from Earth. While a smaller inner planet (GJ 251 b) was previously known, a new 54-day periodic signal—distinct from known activity-related noise—emerged through extensive analysis of more than 900 precision radial velocity observations.

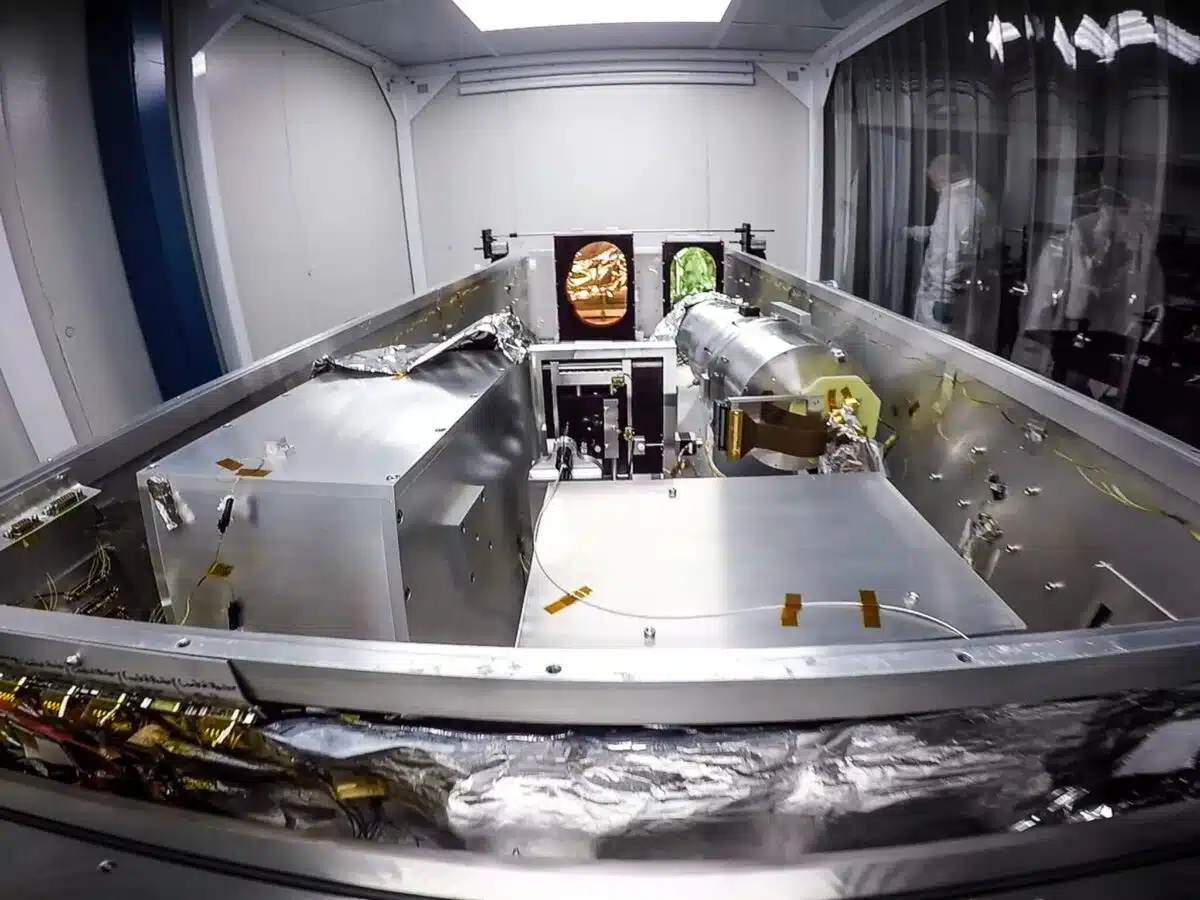

The Penn State University-led Habitable Planet Detector (HPF) provides the most accurate measurements to date of infrared signals from nearby stars. Photo: The HPF instrument during installation in its clean room at McDonald Observatory’s Hobby Eberly telescope. Credit: Guðmundur Stefánssonn/Penn State

The Penn State University-led Habitable Planet Detector (HPF) provides the most accurate measurements to date of infrared signals from nearby stars. Photo: The HPF instrument during installation in its clean room at McDonald Observatory’s Hobby Eberly telescope. Credit: Guðmundur Stefánssonn/Penn State

The newly identified planet, GJ 251 c, exhibits a minimum mass of 3.84 ± 0.75 Earth masses and completes its orbit within the temperate habitable zone, where models suggest surface water could exist if other conditions align. Its likely rocky composition, coupled with its orbit, makes it a plausible candidate for further atmospheric study.

The researchers conducted a Bayesian model comparison across over 50 possible scenarios, comparing models with and without planetary companions. Their analysis found that the presence of GJ 251 c was statistically favored and could not be explained by known sources of stellar variability.

Separating Planetary Signal From Stellar Noise

Detecting small exoplanets around red dwarfs is notoriously difficult. Their stars often exhibit magnetically driven variability, which can produce misleading Doppler signals. To eliminate these false positives, the team used a combination of chromatic Gaussian process models and multi-instrument RV data, ensuring consistency across both visible and near-infrared spectra.

As described in the paper,

“We perform a color-dependent analysis of the system and a detailed comparison of more than 50 models that describe the nature of the planets and stellar activity in the system.”

The team also analyzed multiple stellar activity indicators, including H-alpha, calcium infrared triplet, and differential line widths, to determine whether the 54-day signal could originate from the star itself. Their conclusion: the signal did not appear in any activity proxies and was consistent with a planetary companion.

GJ 251’s quiet stellar environment—confirmed by photometric rotation period estimates of around 122 days—makes it particularly well-suited for the precise RV measurements needed to confirm such a signal. The authors note that GJ 251 is “bright (V = 9.9 ± 0.1) and close (d = 5.58 ± 0.01 pc), making it an excellent target for future direct imaging missions.”

An Ideal Target for Next-Generation Telescopes

Unlike most exoplanets detected to date, GJ 251 c is close enough that it could soon be directly observed via reflected starlight, rather than inferred through indirect means like transits. This would allow researchers to assess its atmospheric composition, temperature, and—potentially—biosignature gases such as oxygen, methane, or carbon dioxide.

“GJ 251 c is currently the best candidate for terrestrial, HZ planet imaging in the northern sky”, According to the authors

Direct imaging of exoplanets requires a rare combination of factors: sufficient angular separation, planet-to-star contrast, and brightness. GJ 251 c checks all three. Instruments like the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) and the Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO), both in development, could be capable of resolving it within the next decade.

The discovery also underscores the growing role of non-transiting planets in exoplanet science. While missions like TESS focus on transits, many of the nearest and most promising exoplanets—like GJ 251 c—do not transit their stars, and can only be detected via radial velocity techniques.