At a distance of 160,000 light-years, an aging red supergiant star in a neighboring galaxy has become the subject of an extraordinary scientific milestone—and a growing astrophysical puzzle.

Captured by the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI), the star, known as WOH G64, is the first ever imaged in detail outside the Milky Way. It resides in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), a satellite galaxy of our own, and is nearing the final stages of its life before a likely supernova explosion.

What researchers found is both a technical triumph and a challenge to established theory: the star is wrapped in a thick, asymmetric cocoon of hot dust, with a structure that current models cannot easily explain. The discovery, detailed in Astronomy & Astrophysics, could reshape how scientists understand the chaotic final phases of massive stars.

The imaging also revealed a dramatic and unexplained decline in the star’s near-infrared brightness over the last decade, suggesting rapid and poorly understood changes in its inner environment. The central question now is whether this behavior is part of an unstable mass-loss episode—or the signature of a hidden binary interaction.

The First Detailed Image of a Star Beyond the Milky Way

Astronomers used the VLTI’s GRAVITY instrument to capture a near-infrared image of WOH G64 at a resolution of 1 milliarcsecond, revealing its innermost circumstellar structure in unprecedented clarity. The observations, taken in late 2020, mark the first successful interferometric imaging of a red supergiant outside our galaxy.

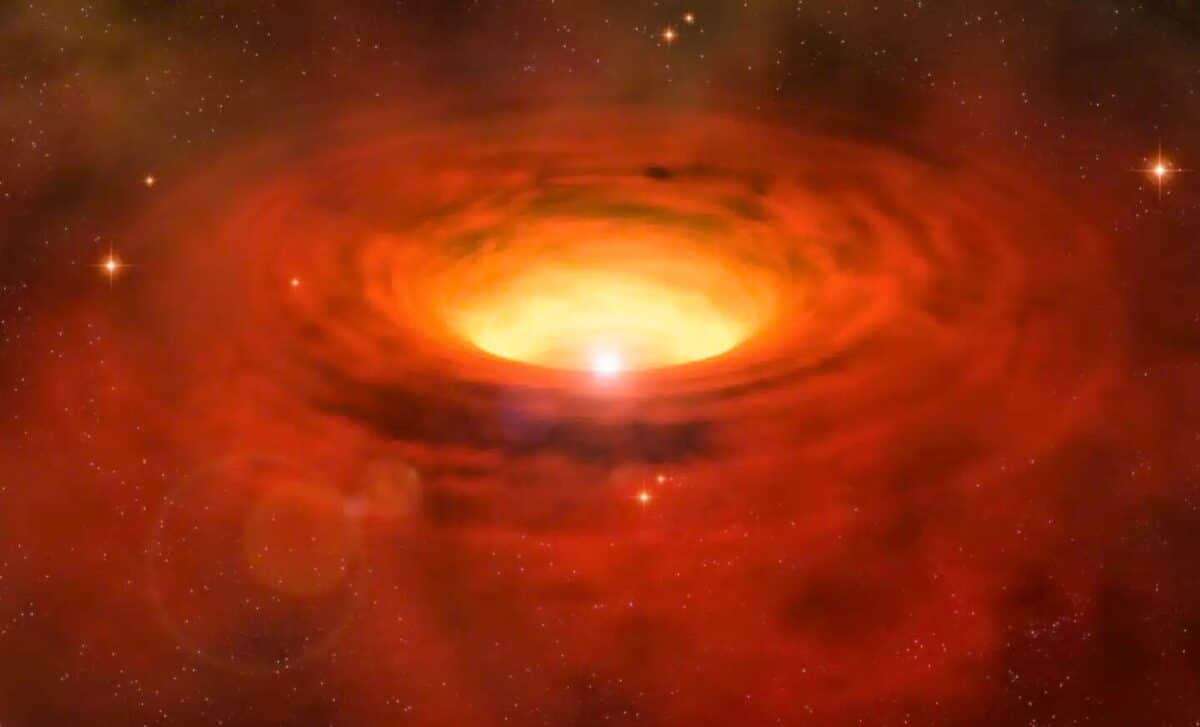

This is the first close-up image of a star outside our own Milky Way galaxy. Credit: ESO/K. Ohnaka et al.

This is the first close-up image of a star outside our own Milky Way galaxy. Credit: ESO/K. Ohnaka et al.

The resulting image shows a compact, elongated emission region, approximately 13 by 9 times the star’s own radius. According to the study’s authors, “the reconstructed image reveals elongated compact emission” inconsistent with the previously accepted model of a spherical or toroidal dust shell.

Notably, the shape of the dust is “characterized by a major and minor axis of ~4 mas and 3 mas,” with the central star itself now barely detectable in the near-infrared spectrum. The team compared their data against earlier models built from MIDI (2005–2007) and Spitzer observations but found significant discrepancies, especially in the expected stellar flux at 2.2 microns.

Sudden Dimming and the Birth of Hot Dust

Beyond the geometry, WOH G64 appears to have undergone a spectral transformation between 2009 and 2016. Earlier data showed classic red supergiant features, such as water vapor absorption bands. But more recent observations—including those from GRAVITY, X-shooter, and the REM telescope—indicate a monotonically rising continuum in the near-infrared.

The study attributes this change to the formation of hot dust close to the star, which now obscures it from direct view. The dust, likely composed of iron-rich silicates or Al-free silicates, formed rapidly and is responsible for the rising infrared flux and absence of molecular absorption lines.

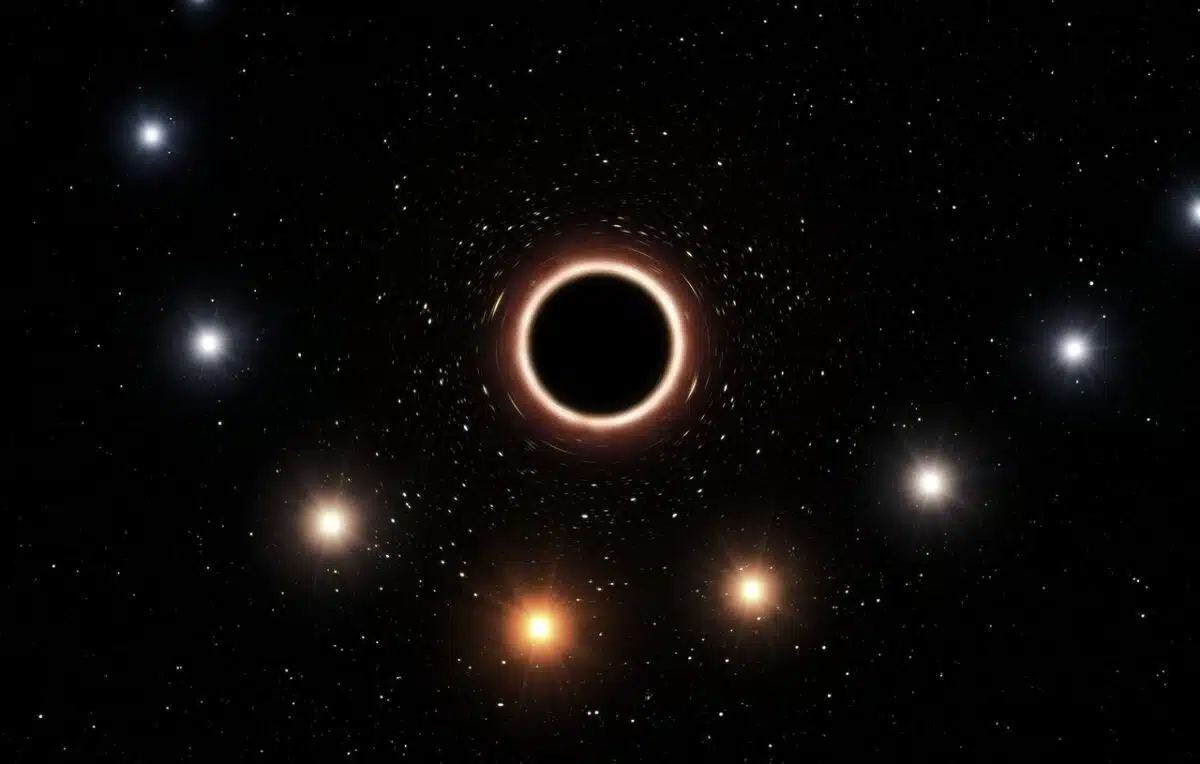

Artist’s impression of S2 passing supermassive black hole at centre of Milky Way. Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser

Artist’s impression of S2 passing supermassive black hole at centre of Milky Way. Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser

“The compact emission imaged with GRAVITY and the near-infrared spectral change suggest the formation of hot new dust close to the star,” the authors write. This dust likely lies within 1 to 2 stellar radii of the surface and absorbs or scatters most of the outgoing infrared radiation.

Interestingly, the mid-infrared spectrum (8–13 μm) has not changed significantly since 2005, based on new VISIR data taken in 2022. This suggests that while the inner circumstellar environment has evolved, the outer dust structure remains stable.

Possible Signs of Binary Interaction

The elongated dust emission raises the possibility of a bipolar outflow or the influence of an unseen companion star. While no direct detection of a companion has been made, the geometry, variability, and dust asymmetry are consistent with non-spherical mass-loss processes.

Earlier studies—including work by Ohnaka et al. in 2008—suggested a pole-on torus could account for the observed structure. However, the current VLTI data show much lower stellar flux than predicted by that model, reinforcing the idea that a new, denser dust layer has formed in the intervening years.

The authors also note that the central star does not clearly appear as a point source in the reconstructed image. While this may be due to obscuration, it also leaves open the possibility that a secondary object may be contributing to the observed structure.

The Unknown Mechanics of Stellar Death

WOH G64 now serves as a real-time laboratory for the study of massive stars in their final evolutionary stages. As the star edges toward collapse, its erratic behavior underscores how much of this process remains poorly constrained—even in stars extensively monitored across wavelengths and decades.

While current theory submits that red supergiants lose mass slowly through spherically symmetric winds, the emerging evidence from WOH G64 paints a more fragmented and episodic picture, potentially shaped by interactions with a companion or internal instabilities not yet fully modeled.

The formation of hot inner dust—seemingly within a few astronomical units—suggests a sudden shift in mass-loss dynamics, the trigger for which remains unknown. The lack of visible light from the star in the last decade also points to a dramatic increase in circumstellar extinction, likely caused by the dust formation event identified in this study.