On October 13, 2025, SpaceX launched what may be its most audacious experiment yet: a high-risk test flight engineered not to succeed, but to stress its Starship system to failure. With critical sections of the spacecraft’s heat shield deliberately removed, the company exposed Starship’s stainless-steel frame to reentry conditions reaching over 1,400°C, in a calculated effort to probe the boundaries of its thermal protection design.

The mission—Starship’s eleventh flight test—marked the final use of its current second-generation hardware. It was also the last time the vehicle will lift off from Pad 1 at Starbase, Texas, before a significant architectural leap to the third generation, or Starship V3. In a program defined by iterative risk, Flight 11 functioned as a deliberate high-fidelity failure study.

The Super Heavy booster flying next month previously launched and was recovered on Flight 8 in March. Credit: SpaceX

The Super Heavy booster flying next month previously launched and was recovered on Flight 8 in March. Credit: SpaceX

SpaceX confirmed in its official mission report that the test achieved “every major objective,” including a full-duration ascent, successful booster landing simulation, deployment of Starlink test payloads, and a key in-space engine relight. Yet what distinguishes this mission is not just what worked, but what was intentionally left vulnerable.

Stress Testing the Thermal Envelope

Starship Flight 11 stands apart for one reason: SpaceX intentionally removed thousands of ceramic thermal tiles, creating unshielded zones on the spacecraft’s exterior to simulate structural failure under extreme heat. According to the mission timeline, Starship successfully reentered Earth’s atmosphere, executed a dynamic banking maneuver, and collected “extensive data on the performance of its heatshield as it was intentionally stressed.”

This high-stakes methodology echoes SpaceX’s long-held philosophy of data-driven iteration. The company has historically chosen to test complex systems in flight rather than rely exclusively on simulations or lab tests, an approach that has yielded rapid design evolution but also attracted regulatory scrutiny.

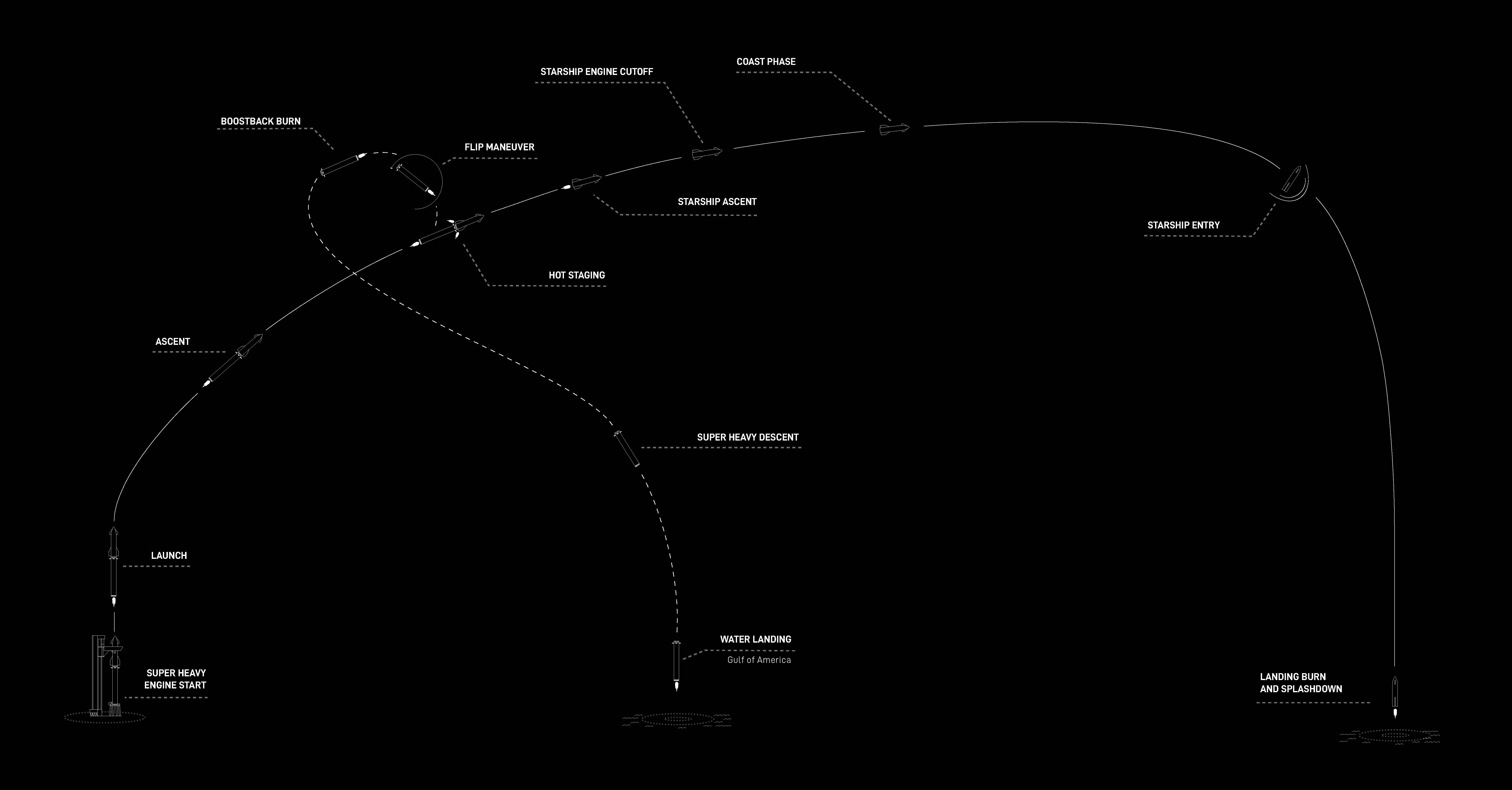

This graphic provided by SpaceX illustrates the flight paths of the Super Heavy booster and Starship upper stage on Flight 11. Credit: SpaceX

This graphic provided by SpaceX illustrates the flight paths of the Super Heavy booster and Starship upper stage on Flight 11. Credit: SpaceX

Unlike previous flights, where full shielding was intended to prevent heat-induced damage, this test welcomed it. The deliberate exposure of structural elements created a unique opportunity to observe how the vehicle reacts to direct plasma heating during atmospheric descent—a critical factor for rapid reuse.

The reentry phase concluded with Starship performing a landing flip and controlled splashdown in the Indian Ocean. The maneuver closely simulates the trajectory Starship is expected to use during future land-based returns to Starbase.

Super Heavy’s New Descent Strategy

The booster—Super Heavy B15—was also a focal point of the test. First flown in March 2025, it returned for this mission equipped with 33 methane-fueled Raptor engines, 24 of which were flight-proven. As reported by Ars Technica, the vehicle executed a modified landing sequence, transitioning from a 13-engine burn to five, before completing the descent with three central engines.

This new 13-5-3 engine sequence replaces the previous 13-to-3 approach and is designed to provide redundancy against spontaneous engine shutdowns, a risk inherent in high-thrust deceleration. SpaceX confirmed that the sequence was completed successfully, including a brief hover over water before splashdown.

The adaptation directly supports the company’s long-term goal of catching returning boosters using the mechanical arms of the Starbase launch tower—a maneuver that will require millisecond timing and absolute precision. This test marks a step toward that vision, validating control systems and engine management under real-world stress conditions.

Advancing In-Space Capability

Starship’s upper stage completed a full-duration burn, achieved its targeted orbital trajectory, and conducted a test deployment of eight Starlink simulators, SpaceX reported. The exercise served not only to validate deployment hardware but also to test orientation control and structural integrity under load—a necessary precursor for orbital payload operations.

A view of the Starship’s upper deck on re-entry on October 13, 2024. Credit: SpaceX

A view of the Starship’s upper deck on re-entry on October 13, 2024. Credit: SpaceX

Perhaps more consequential was the third successful in-space Raptor engine relight, a capability central to complex missions such as orbital rendezvous, lunar descent, or planetary return. According to SpaceX’s mission summary, the relight “demonstrated a critical capability for future deorbit burns.”

Starship also completed a dynamic descent profile resembling future return-to-launch-site operations. These refinements are essential not only for commercial reuse, but also for NASA’s Human Landing System, where Starship will play a pivotal role in transporting astronauts from lunar orbit to the Moon’s surface and back.

The Road to Starship V3 and Orbital Operations

Flight 11 concludes the development arc of the second-generation Starship system. With this final iteration tested, SpaceX now turns its focus to Starship Version 3—a major redesign featuring enhanced propellant capacity, orbital refueling support, and a larger physical profile.

As confirmed by Ars Technica, the first flight of V3 is slated for early 2026 and will lift off from a newly outfitted launch pad near the original Starbase site. The V3 variant is expected to attempt full orbital insertion and serve as the first platform for cryogenic propellant transfer in orbit—a maneuver no agency or company has successfully executed.

NASA’s Artemis architecture depends heavily on this capability. Without orbital refueling, Starship lacks the propulsive margin to complete round-trip missions to the lunar surface. The coming year will test whether the vehicle—and the architecture behind it—can meet those requirements.