This marks the first time scientists have confirmed a coronal mass ejection (CME) from a star other than the Sun—an event powerful enough to compromise the habitability of entire planetary systems.

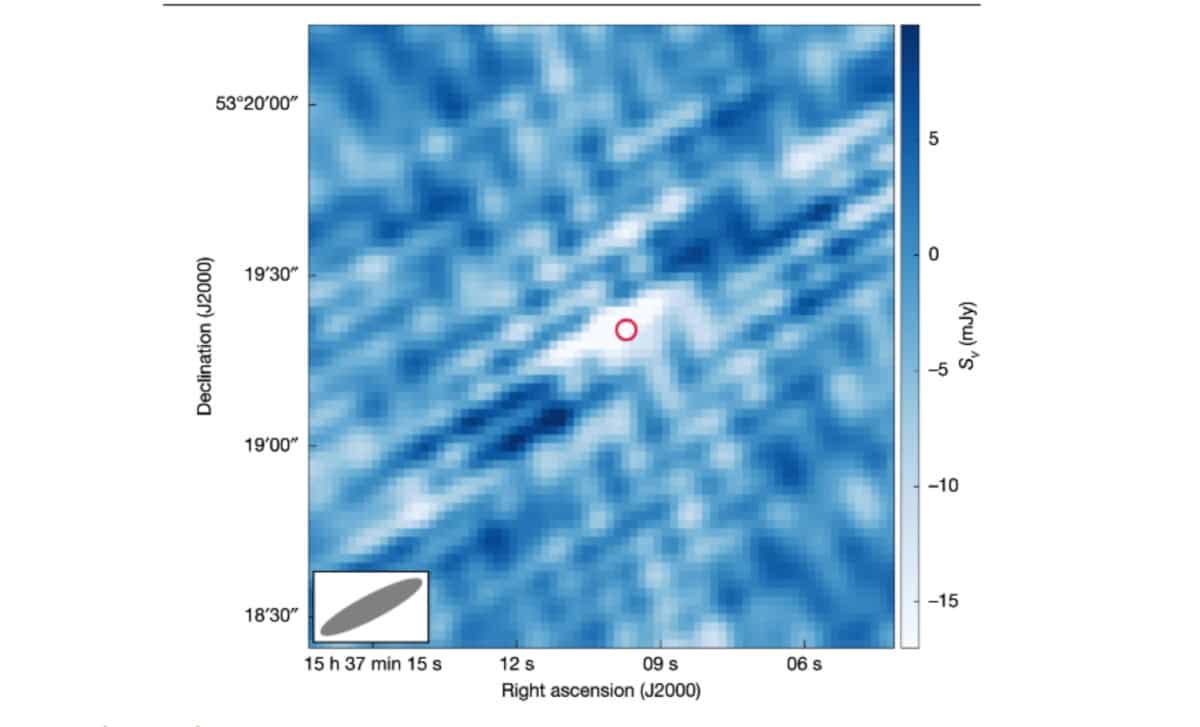

The blast was observed by a network of telescopes led by the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR), and it could dramatically shift how researchers evaluate the chances of finding life beyond Earth. The star, known as StKM 1-1262, now serves as a critical case study in the risks posed by stellar outbursts to Earth-like planets.

M dwarfs, the most common type of star in the Milky Way, have been prime targets in the search for habitable worlds. Their smaller size and lower luminosity make it easier to spot exoplanets orbiting nearby. But this new observation casts a shadow over their potential, revealing a hazard that could wipe out atmospheres entirely—without any warning.

First Confirmed Stellar CME Beyond the Sun

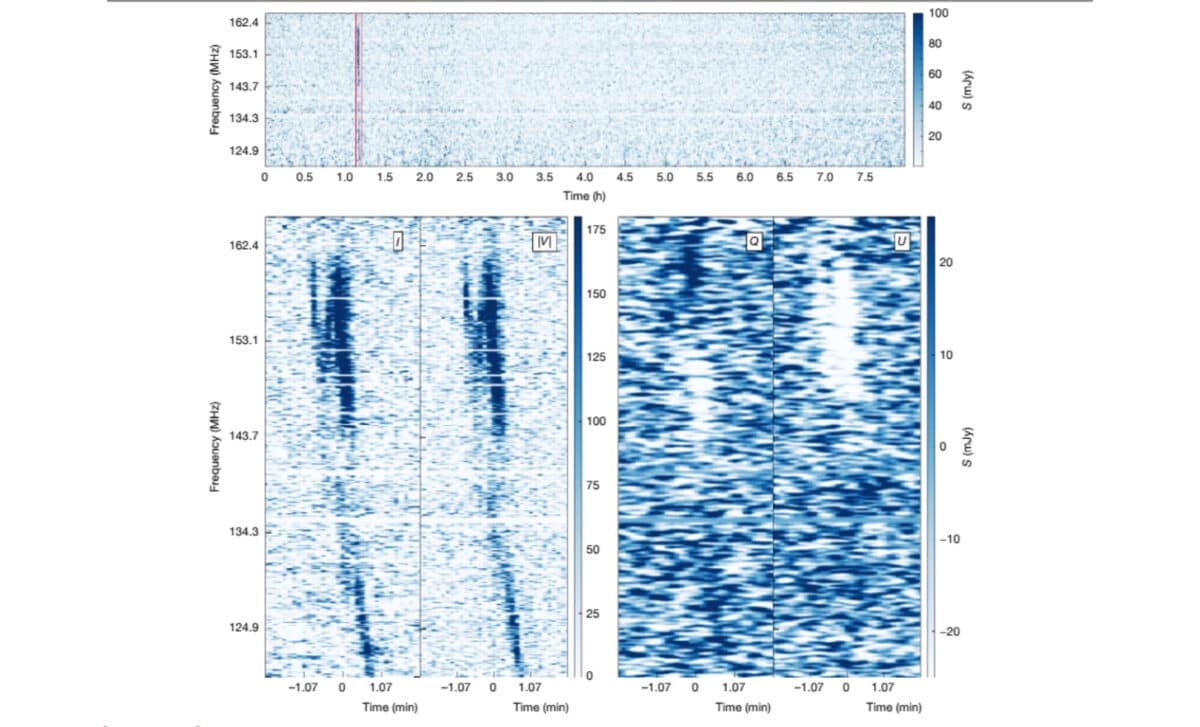

The event began as a faint burst of radio waves detected by LOFAR, a vast radio telescope spread across Europe. Using enhanced data-processing techniques developed with researchers at the Paris Observatory, the team identified signs of a CME—a high-velocity eruption of plasma and magnetic fields.

To verify the finding, astronomers turned to the XMM-Newton space telescope, operated by the European Space Agency. According to Live Science, these follow-up observations confirmed that StKM 1-1262 is an M dwarf, spinning nearly 20 times faster than the Sun and emitting strong X-ray radiation—all signs of intense magnetic activity.

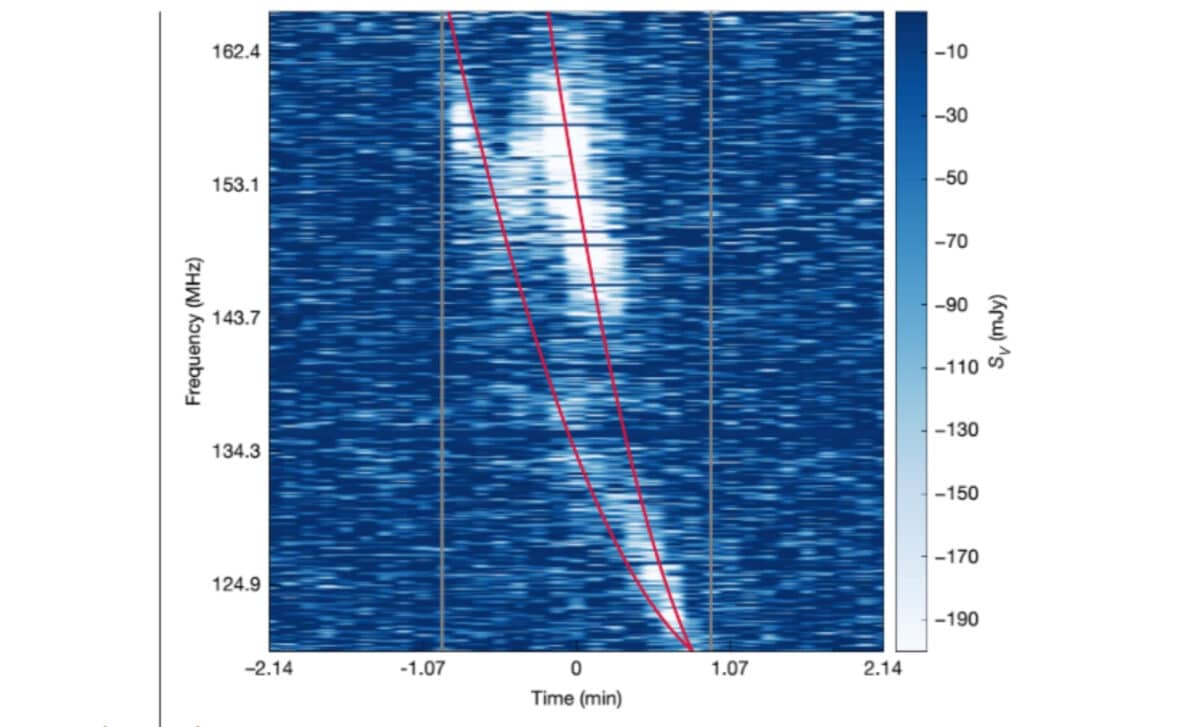

The CME itself was moving at about 2,400 kilometers per second, one of the fastest ever observed. This rare velocity, recorded in only about 5% of similar solar events, meant the eruption carried enough energy to strip away the atmosphere of any planet orbiting nearby. Lead study author Joe Callingham noted that such events could be fatal to planetary habitability, saying, “So, great — you’re in the Goldilocks zone, but you’ve got no help here, because the stellar activity destroyed [the chances for life],” as reported by the same source.

Repeated CMEs Could Sterilize Otherwise Habitable Planets

The implications of this discovery are hard to ignore. While M dwarfs are widely seen as promising sites to discover Earth-like exoplanets, their aggressive behavior may nullify the very habitability they seemed to offer.

As Callingham explained, planets orbiting within the habitable zone of such stars are likely to be bombarded by CMEs far more frequently than Earth is. Because the habitable zone is much closer to the star, any rocky planet located there would endure constant exposure to extreme space weather, possibly losing its atmosphere altogether.

This makes detecting atmospheres around exoplanets more difficult and casts doubt on previous estimates of how common habitable planets might be. The idea that a planet is in the “right spot” isn’t enough if it’s being hammered by radiation and plasma storms on a regular basis. The CME from StKM 1-1262 brings this concern into sharp focus, demonstrating the real possibility that life-friendly planets might be far less common around M dwarfs than hoped.

circularly polarized burst – © Nature

New Telescopes Aim to Uncover the Scale of the Threat

While the LOFAR telescope was instrumental in this detection, the team acknowledges that it is nearing its observational limits. To dig deeper into the nature and frequency of CMEs beyond our solar system, researchers are now looking ahead to the Square Kilometer Array—a next-generation radio observatory under construction in Australia and South Africa.

Callingham and his colleagues believe this new array will detect dozens or even hundreds of extrasolar CMEs once it begins operations in the 2030s. This expanded dataset could help astronomers understand how often these destructive blasts occur and how they vary depending on the type of star.

duration of 2 min burst – © Nature

“We really are, as astronomers, trying to find a habitable planet,” Callingham said. “It’s one of the key goals of astronomy… But maybe it’s going to take longer, or maybe the rest of my life, to find Earth 2.0.” His words underscore a growing recognition within the field: until we understand stellar violence, we may be chasing a mirage in our search for another Earth.