In 2019, in a laboratory buried under an Italian mountain, an extraordinarily rare event was picked up by an instrument designed to hunt the invisible. Researchers from the XENON collaboration observed the decay of a single atom of xenon-124. Nothing unusual at first glance, except for one detail: this isotope has a half-life of more than 18 sextillion years – over a thousand billion times the current age of the universe. An event this unlikely and unexpected happened inside one of the most sensitive detectors ever built.

Far from being a mere technical footnote, this atomic decay showcases science’s growing ability to capture the faintest phenomena and push the boundaries of what can be measured.

When decay becomes (almost) eternal

The idea of half-life is well known: it is the time it takes for half of a given amount of a radioactive isotope to transform into another atom. In most cases, this transformation happens on human or planetary timescales. Carbon-14, for example, has a half-life of 5,730 years, which makes it useful in archaeology. Uranium-238 takes 4.5 billion years for half of its atoms to decay.

But xenon-124 belongs to an entirely different league: its half-life is estimated at 18 sextillion years (18 followed by 21 zeros). On that scale, even cosmic timespans start to look small. If you placed a single gram of xenon-124 somewhere isolated in the universe, it would remain almost unchanged long after every star had burned out.

Observing the unobservable: the XENON1T experiment

So how can a decay this unlikely ever be detected? The answer lies in the sheer scale of the experiment. The XENON1T detector, located deep inside the Gran Sasso underground laboratory, contains two tons of ultra-pure liquid xenon. That corresponds to nearly 10,000 billion billion atoms of xenon-124.

With that much material, even an event that happens only once every 10^22 years for a single atom can, statistically, show up a few times per year in the detector as a whole. Over 177 days of operation, the team managed to observe nine decays of xenon-124.

These decays do not produce visible flashes of light or dramatic explosions. They emit extremely faint signals, such as X-rays or electrons, which XENON1T’s ultra-sensitive sensors can pick up in the near-total silence of its underground environment.

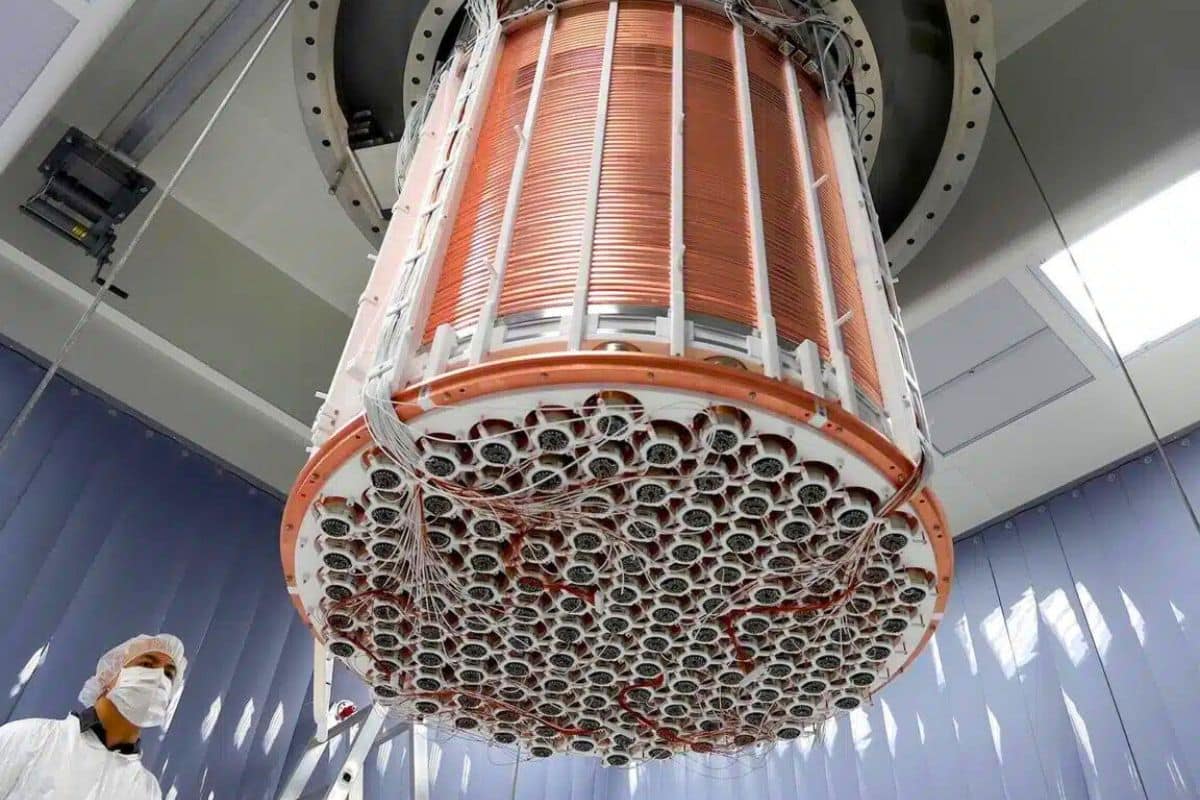

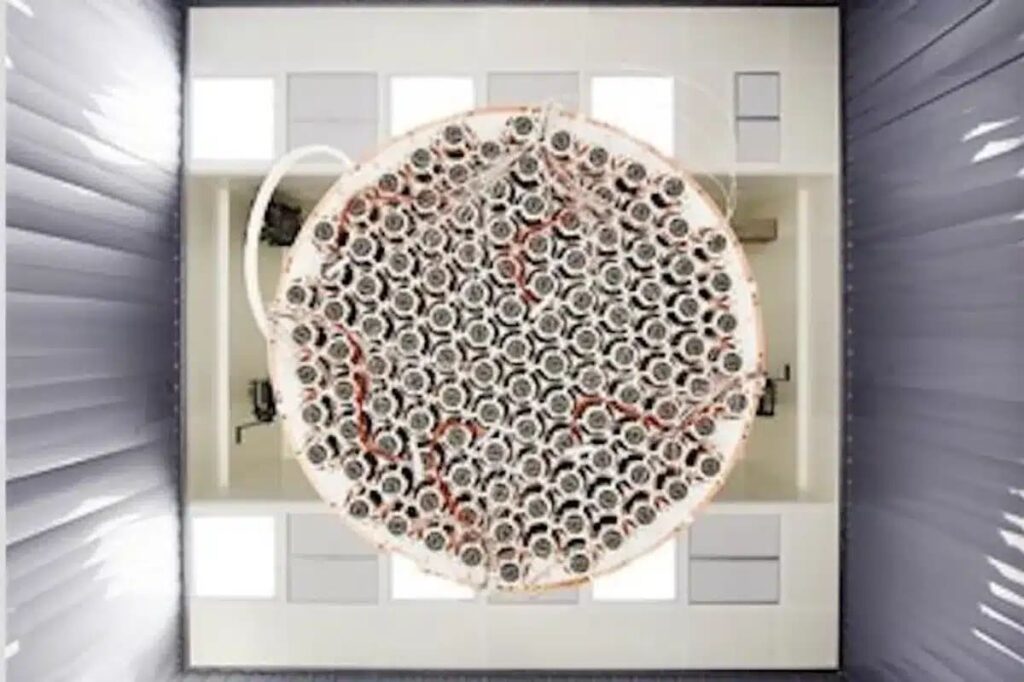

The photomultiplier tubes of the Xenon1T detector, used to detect dark matter and, in this case, a rare decay. Image credit: Xenon1T

Why this is a major breakthrough

At first glance, this discovery might seem anecdotal. After all, it concerns a rare isotope in a very specific experimental setup. But its implications are much broader. To begin with, it is a technical and scientific tour de force: being able to observe such rare processes shows that our instruments have reached a remarkable level of precision.

It also opens the door to detecting other ultra-slow phenomena, such as proton decay. Some grand unification theories predict that this particle, one of the fundamental building blocks of matter, could decay with a half-life even longer than that of xenon-124 – more than 10³⁴ years, according to some estimates.

So far, no proton decay has ever been observed. But the XENON experiment demonstrates that with enough material, patience and precision, even the most improbable events can eventually be caught in the act.

A new frontier for fundamental physics

The decay of xenon-124 does not overturn our current understanding of physics, but it does confirm certain theoretical predictions and strengthens the case for models that have not yet been thoroughly tested. It also reminds us that even extremely stable isotopes are not truly eternal and that everything, even what seems frozen in time, ultimately changes.

Finally, it underscores a key lesson of modern science: just because a phenomenon is rare does not mean it is out of reach. Sometimes, all it takes is looking in the right place, for long enough, with the right tools.

The details of the study were published in the journal Nature.